In my 20s and reeling from a break-up, I read everything best-selling Japanese novelist Haruki Murakami had written, drowning myself in his prose the way others might in bottles of whisky.

I have never been a fast reader, but his lonely charismatic male protagonists and pacey yet meditative narratives - thrillers that make you ask "why" rather than "who" - made it easy for me.

On weekends and when I did not have to work, I read through the night, coming up for air the next morning.

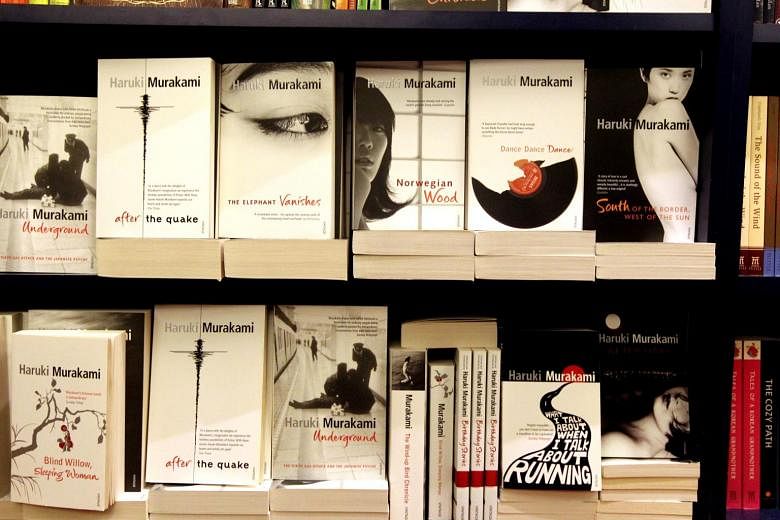

In that way, I tore through eight novels and short story collections in a few months - at that point, the sum total of his output that had been translated into English.

Fifteen years on, as a time-strapped working mother of two, I recently picked up Mura- kami's Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki And His Years Of Pilgrimage (2014) and wondered if I would still find him appealing.

A perennial favourite to win the Nobel prize for literature as well as a recurring presence on bestseller lists around the world, his fame had grown in the intervening years, but I had not read anything by him in nearly a decade. Would I see my younger self in his fiction and cringe? Or would I discover something more enduring, something that could still speak to me even as I entered the fifth decade of my life?

For readers like me, who have spent part of our lives submerged in the printed word, these are important questions. Finding a writer for all seasons is like stumbling on that pair of navy slim-cut jeans at the back of your wardrobe that, two pregnancies later, miraculously fits you like a second skin. It is unearthing the Cleopatra of authors - "age cannot wither her, nor custom stale her infinite variety", as Shakespeare wrote famously of the legendary Egyptian queen.

Unlike theatre and film, where a director's update in all its technicolour glory can blow the dust off an old script, fiction stands or falls solely on the resonances of the written word. Although a recent re-read of the 19th century Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen reminded me that great writers need no help; his cool, coiled Hedda Gabbler who burns with an inner restlessness and fury over the dead ends in her life, is as much a feminist symbol as Ali Smith's Renaissance painter in male guise in How To Be Both (2014), which won the Baileys women's prize for fiction last month.

Writers write what they know, so it is a truism that an author may write the same novel over and over again throughout his career, with only subtle variations.

More power then, to the shape- shifters who don't, like Kazuo Ishiguro, the literary world's Lee Ang with a similar ability to navigate with ease different genres, historical periods, narrative styles and concerns. His latest novel, the fantasy-drenched The Buried Giant, sits tantalisingly on my shelf.

It was as an 18-year-old that I first read The Remains Of The Day (1989), the Japan-born British novelist's breakout study of repressed ambition and desire through the eyes of an old English butler.

His subsequent novels have only grown for me in their power, from the deliciously absurdist narrative of The Unconsoled (1995), an unravelling of the delusions and sacrifices underpinning one concert pianist's existence, to the wrenching When We Were Orphans (2000), about an idealistic English detective's attempt to solve the mysteries of his childhood in early 20th-century Shanghai.

At its kernel is the depths to which a mother would go to preserve her child; reading it as a first-time mother a few years ago, it hit me like someone had punched me in the gut.

Then there are writers whose prose crackles with such electricity and insight that the story they are telling is almost secondary. American novelist Don DeLillo falls into that category; his staccato-like, densely poetic, subversively ironic voice is the same from White Noise (1985) to Cosmopolis (2003), but it stops you dead in your tracks anyway.

Like DeLillo, Murakami doesn't change much from novel to novel, though he is a storyteller first and a wordsmith second, perhaps because one is reading him in translation. Nonetheless, I have come to acknowledge the not insignificant role his fiction has played in my life.

During the time of my literary obsession with the Japanese jazz bar owner-turned-writer, I wrote a column about him. It was a serious analysis, mind you, with some personal musings thrown in, but a cheeky sub-editor had given it the headline, "Where can I find a Murakami man?", followed by the deck, "He's a loner, listens to jazz and cooks well. Unfortunately, he's also a figment of Japanese novelist Haruki Murakami's imagination".

An acquaintance of mine read the newspapers, was surprised he fit the description of the kind of man I was looking for and cut out the newspaper column, sticking it on his refrigerator door.

Fast forward to over a decade later, and I am living in a crowded apartment filled with his jazz and classical albums, kitchen implements, books and paintings and the noisy shrieks of two perpetually fighting children who have his eyes and my smile.

Reading Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki recently, what struck me was that Murakami's concerns had also evolved and become more philosophical and incisive.

The story of an engineer trying to reconstruct the mystery of why he was abandoned by his five childhood best friends is carefully plotted - a coming-of-age story and romance with all the twists and turns of detective fiction, like many of Murakami's early novels.

What comes out most strongly this time, however, is the rumination on an individual's dark side, the aspects of one's past and personality that one prefers to keep buried, and how this manifests itself in dreams and the subconscious before reaching a tipping point. These are the strands from Murakami's later epic novels such as the sprawling The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle (1997) and Kafka On The Shore (2005), now distilled into a more compact form.

It dawned on me that what is East-meets-West about Murakami, now in his 60s, is no longer just his debt to Western authors such as Raymond Chandler or the classical and jazz references, but his ability to channel both Freud and the Asian spirit world into a coherent narrative, drawing on the power of both. That was what made Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki a page-turner for me and I downed it in one weekend.

Perhaps that is one of the thrills of following a living author's career over time - he ages as you age, your awareness of birth, death and all of life's variegated shades in between shadowing his.