Secrets and friendship

Hanya Yanagihara and Sunjeev Sahota were both on Man Booker shortlist for second novels partly inspired by family history

The Man Booker Prize was won last week by Jamaican writer Marlon James for A Brief History Of Seven Killings, though bookies favoured one of two second novels of astonishing power on the shortlist.

Both books are about secrets, loneliness and male friendship, and are somewhat inspired by the writers' immigrant family history.

Life learns the stories behind American author Hanya Yanagihara's A Little Life and British author Sunjeev Sahota's The Year Of The Runaways.

A piece of his family in history

Sunjeev Sahota shared his first home with 12 people including uncles, aunts and cousins, in the traditional joint-family set-up of the British-Asian community.

"I can see how that idea of sharing space, rooms, beds, might have found its way into the book," writes the 34-year-old author in an e-mail interview.

He is referring to his second novel, The Year Of The Runaways, which was described by award- winning Pakistani novelist Kamila Shamsie as "brilliant and beautiful" in her review for The Guardian newspaper.

The Year Of The Runaways is about 13 male transient migrants from India, who live in the same house in Sheffield and are exploited in their low-wage jobs at construction sites or fast-food restaurants. They share household chores and food expenses, but abandon the ties of friendship when jobs are in short supply.

Sahota knows a bit about the loneliness and social alienation immigrants face. His grandparents and father migrated from Punjab in India in the 1960s. His grandfather worked in an iron foundry in Derby while his father ran a shop.

"Given my family history, it would have been surprising if the subject hadn't cropped up in my fiction," the author explains his inspiration for The Year Of The Runaways.

"The spark was probably the decision in the autumn of 1946 to partition Punjab in two. It led to a series of migrations in my family whose effects are still being felt today."

That division of the state of Punjab into two of the same name, one in Pakistan and the other in India, led to one of the greatest mass migrations in human history.

Millions forced out of their homes moved not only between the newly independent countries of India and Pakistan, but also to places as far away as Hong Kong, Singapore and Kuala Lumpur, as well as England and America.

Sahota's first novel, Ours Are The Streets (2011), looked at immigration and integration. The book is set in Sheffield where he lives with his wife and daughter and near his parents, and was told through the eyes of the son of a Pakistani immigrant, a young British man who becomes a suicide bomber.

Booker alumnus Salman Rushdie picked Ours Are The Streets for influential literary magazine Granta's Best Of Young British Novelists' selection in 2013.

He wrote of the book: "The real thing: It declares itself instantly and all you can do is surrender, happily, to its power."

Oddly, Rushdie's Booker Prize- winning novel Midnight's Children was the first full-length work of fiction Sahota read. He was 18 at the time.

"Somehow, we weren't required to read a full novel at school. It wasn't until I was 18 and boarding a flight to India that I picked up my first novel, Midnight's Children," he says, though he did read newspapers and magazines.

He studied mathematics at Imperial College and worked in marketing teams for finance companies before quitting his job to write full-time.

He writes his first draft on the computer and revises it by hand, working indoors and with curtains drawn to shut out natural light.

"I'm far too easily distracted," he says.

Perhaps that is why his books are structured around such polarising themes as immigration and social alienation.

"I want to write about real characters in interesting situations. That's what's going to keep me going and engaged for the length of time it takes me to write a novel," he says.

•The Year Of The Runaways (Picador, $31.95) is available at Books Kinokuniya.

Photos of men and motel rooms inspire dark tale

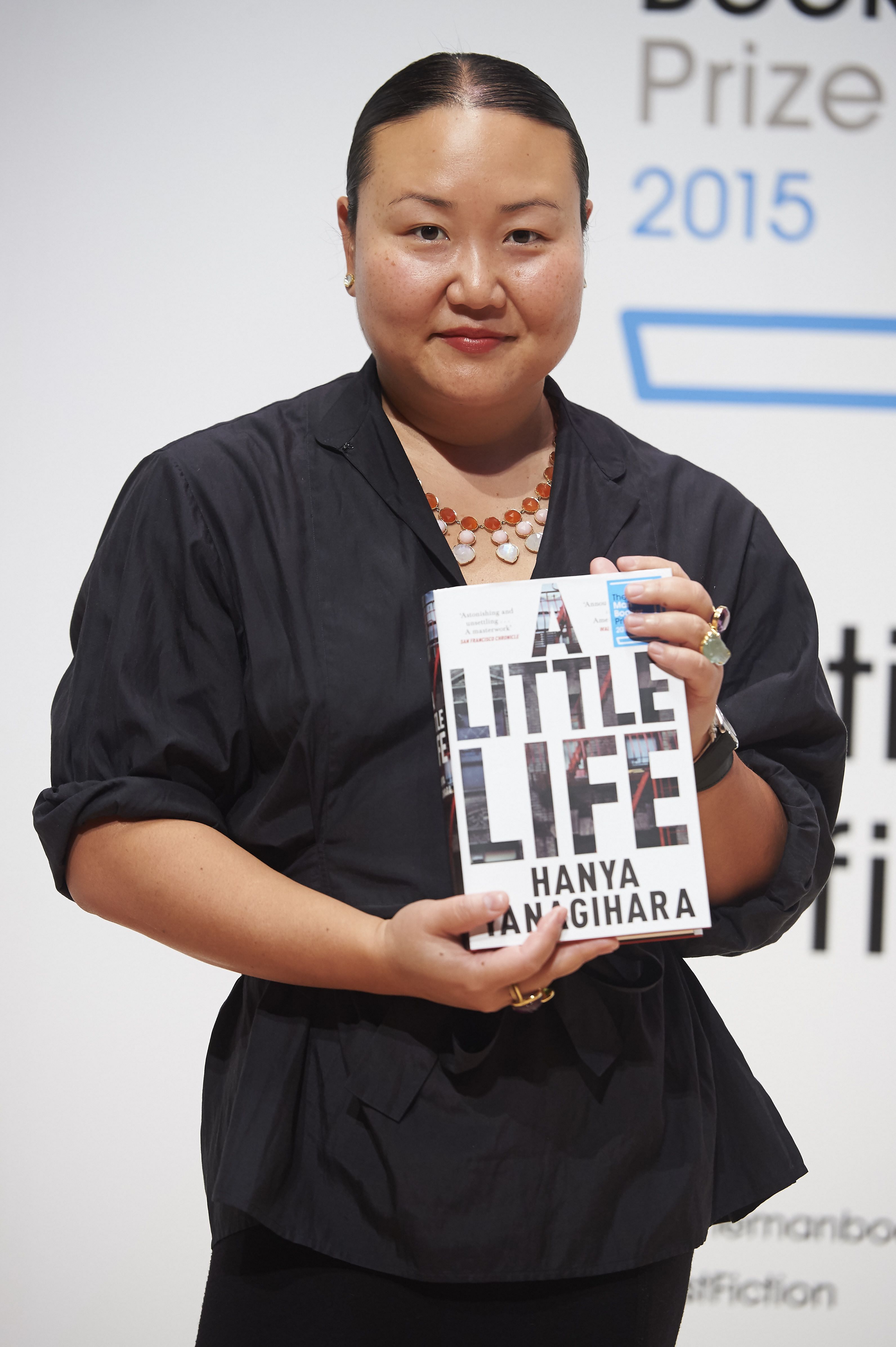

Before the Man Booker Prize judges announced the winner last Tuesday, Hanya Yanagihara's brick-thick A Little Life was the bookie's favourite to take the £50,000 (S$107,000) award.

Not only was the 720-page novel the biggest in the running for a prize that traditionally favours longer books, but its deeply felt portrait of four inseparable male friends living in New York City left more than one reviewer sobbing - and gushing - in print.

Yanagihara's creative process began 14 years ago, with her collecting photographs of men and motel rooms that eventually inspired much of the novel's imagery and textual sensuality.

The actual narrative was written in 18 months and she is still recovering from the intensity of the work.

"It's a book that demanded a huge emotional surrender," she says in a telephone interview from London, where she attended the Man Booker award ceremony.

"With a work like this, you don't decide when you're done with it."

The novel alternates heart- melting portraits of affection between friends, who become each other's chosen family, with harrowing descriptions of the abuse that central character Jude suffered as a child.

Yanagihara, 40, calls A Little Life "an answer" to the questions she posed in her first novel, The People In The Trees, which had as its protagonist an abuser.

"It's not about child abuse as it is about the abuse of power," the author corrects.

She also draws on the feelings of powerlessness and insecurity she experienced as a child, albeit one with devoted parents. Her parents were raised in Honolulu and are the first generation "who made it into the middle class". They left the island for her oncologist father's studies. The family moved around America whenever there were better opportunities, her parents refusing to take flights to save money.

Some of Yanagihara's childhood memories involve stark motel rooms - similar to the ones her character Jude inhabited as a child - where she and her brother waited quietly, told not to disturb their exhausted father while their mother went to the grocery store.

"We knew we would always be taken care of, but you realise how much of your childhood is about loneliness and fear," she says.

"Children are so much at the mercy of others. They are resourceful, but they are in a world where they don't know the rules."

Yanagihara is not married and has no children, though she has just been asked to be godmother to her friend's child.

Like the characters in her book, her "family" involves friendships, such as with New York magazine editor Jared Hohlt, to whom A Little Life is dedicated.

It is a social structure she thinks is unique to "vast countries" like America where people travel for work, where "the idea of filial piety and taking care of family is not an absolute".

Her parents have been supportive of her career, though her father initially wanted her to be a pathologist.

When Yanagihara was 10 or 11, she thought she might become an artist and he got a friend at the mortuary to let her study cadavers.

That scientific interest in what makes people tick was reignited after Yanagihara graduated from the all-female Smith College in Massachusetts and joined the world of magazine publishing, where she had far more male colleagues than in her previous job in female-dominated book publishing.

"I have many female friends, I adore them and understand them to a better degree," she says.

She was fascinated by the differences in how male friends communicated with one another versus their female friends, including the physicality of their affection.

A Little Life grew in part out of these observations.

From that first job in the now- defunct magazine Brill's Content, about the media industry, she is deputy editor at The New York Times' style magazine T Magazine.

She enjoys her work so much that she sees herself as "someone who writes books on the side" and credits her day job for teaching her important "but unglamorous" things about the craft of writing, such as the importance of sending in a clean first draft.

"I'll always have a job of one sort or another," she says. "It's important for writers to be out in the world. It's an important refresher on how people think and talk."

In spite of believing in the importance of human connections, Yanagihara also thinks loneliness is "a fact of life".

This belief is at the core of A Little Life, which is about how relationships may nurture but not necessarily save a person.

"Every thinking person is also a deeply lonely person. So much of heartache comes from thinking being surrounded by people is going to dispel this sense of loneliness and that's not true.

"It's the human condition to be alone... there isn't any running away from it."

•A Little Life (Doubleday, $32.95) is available at Books Kinokuniya.

Join ST's Telegram channel and get the latest breaking news delivered to you.

A version of this article appeared in the print edition of The Sunday Times on October 18, 2015, with the headline Secrets and friendship . Subscribe