Poetry - too highbrow for the masses?

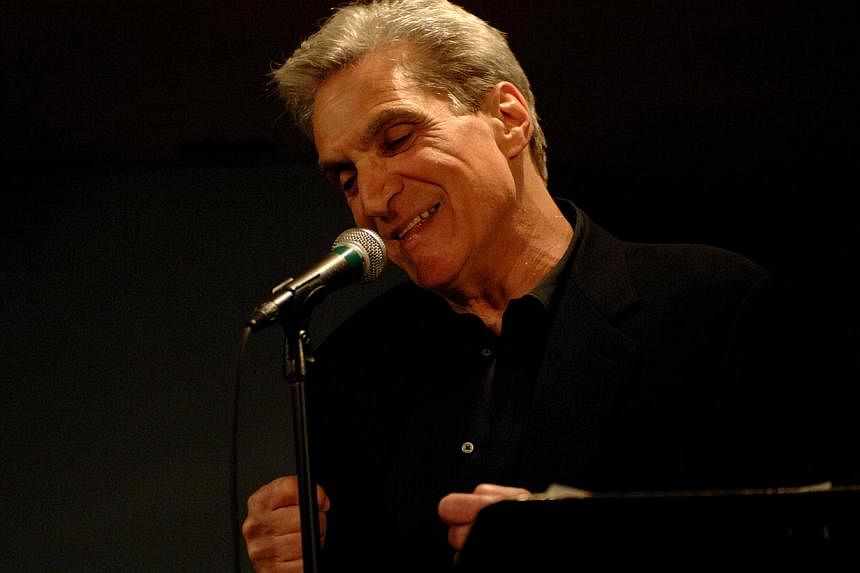

Never, according to American poet Robert Pinsky, one of the most public advocates of poetry in the United States.

The 74-year-old, who was the US Poet Laureate for three terms running (1997- 2000), cites a video from his Favourite Poem Project, in which a construction worker passionately recites and discusses Walt Whitman's Song Of Myself. Thousands of Americans have shared their favourite poems through this project.

Pinsky says: "Those people, the videos, the books, relieve me from any necessity to dismantle anything or to promote anything. The readers and the poems speak for themselves."

He is a fierce believer that poetry is "fundamental" to human existence.

"If we judge any group new to us - a family, a tribe, a city, a country - perhaps the two most vital questions are: 'Do they care for the children?' and 'Do they care for the old people?' If those duties are neglected, something has gone terribly wrong," he says.

"And the two questions are profoundly related: In a proper culture, we owe it to those two groups that we pass on the songs, poems, recipes and wisdom of the old ones to the young. Like cuisine, dance and music, poetry is in all cultures a fundamental element in that process."

The poet's deep fascination with the musicality of the English language is also something that recurs in a combination of e-mail interviews and a telephone conversation from his home in Massachusetts, where he teaches at Boston University.

He will bring that musicality here for the Singapore Writers Festival, during which he will discuss poetry with Pulitzer Prize-winner Paul Muldoon, have lunch with readers and perform poetry with jazz musicians Rick Smith and Christy Smith in a session of PoemJazz.

Pinsky himself has music in his veins - he played the saxophone as a young man and was voted Most Musical Boy in school. These days, he often recites his poetry and pairs it with music without too much preparation. "Preparation makes me nervous. I prefer improvisation," he says.

It is this improvisatory, free-form approach that makes PoemJazz so engaging. "It's not setting poetry to music," he clarifies. "This is more like rap, it's poetry that becomes music, which is like rap - but a completely different verbal idiom and a completely different musical idiom. It's not like a song, in which you set the words to music. This is the melody of the words in conversation with the melody of the music."

He recalls how the brother of a friend, poet Charles Simic, booked them into the Jazz Standard, a prominent jazz club in New York, many years ago, together with drummer Andrew Cyrille and vibraphone player Mike Mainieri.

Pinsky says: "Something happened when we were doing my poem Ginza Samba. The musicians and I were in a sort of call and response element and the rhythms of the words. I was listening to them, they were listening to me, and we made something that was musical."

Pinsky never consciously decided to become a poet. He was born in New Jersey to Jewish parents, and his optician father, Milford Simon Pinsky, is featured in one of his popular poems, titled Creole.

He says: "My parents and grandparents and their relatives and friends were expert joke tellers, complainers, arguers. I come from a richly verbal, amusing and contentious household. I never decided to 'be a poet'. Indeed, I decided to be a musician.

"But all the time, I was thinking about the sounds of words and the melodies of sentences. And one thing led to another. My parents were neither encouraging nor discouraging. They were odd and brilliant and they expected the same of me, I think."

He went on to receive his Bachelor of Arts from Rutgers University and did his master's and PhD at Stanford University, where he was a Stegner Fellow in creative writing. His poetry is known for its musical musculature, with great care taken to the shape and structure of every sentence, and how each word sounds in the mouth as it is spoken.

One of his most recognisable poems, Shirt, traces that tangible common object through the press of history and time and the lives that have shaped it. You can almost feel the stitching and the warmth of an ironed shirt on your back.

He dissects his process of creating Shirt: "It's more like sandpapering something or rehearsing a musical piece than it is like finishing a legal brief or writing a term paper. It feels right."

He spent a great deal of time mulling over many separate ideas, including the 1911 fire at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory in New York City, the deadliest fire in the city's history, and all the labour poured into the creation of an object, whether by living people or his own ancestors.

But "that's not the poem", Pinsky emphasises. "The poem is thinking about 'the needle, the union, the treadle, the bobbin', and you get the nouns associated with that trade, and that poem goes many places. I steal a sentence here, I take an idea there, I think about the hoax of Ossian, I think about George Herbert, I think about Koreans, I think about my grandmother's sewing machine - and it's a tune that holds them together, it's a kind of music that goes with the emotions and the ideas."

It is this sort of unpacking that Pinsky does best, and his love of not just the etymology of words, but also "the figurative etymology of everything".

"I like knowing a bit about the history of paper or pornography or noodles or the trombone, as well as words."

For more information about the Singapore Writers Festival, go to www.singaporewritersfestival.com