NEW YORK • One of the best presents that Mr Asi Sharabi received was a bad book.

It was a customised book for his three-year-old daughter, Thalia, and apart from the initial thrill of seeing her name in the story, there was not much to distinguish it from a mediocre mass-produced picture book.

"It was underwhelming," he said.

But it eventually led to an idea: What if you could use technology to fashion a story for each young reader and create a more sophisticated children's book?

Mr Sharabi consulted two friends, a writer and a technologist. They decided to try it themselves.

They came up with a story about a child who has forgotten his or her name and goes on a journey to find it, encountering creatures and characters that provide clues. A boy named Sam, for example, will meet a squid, an aardvark and a mermaid, who each present him with a letter of the alphabet.

The technologist, Mr Tal Oron, designed software to generate individual versions of the book based on particular names.

They tested the name Andrew first. It worked. Nearly four years later, their company, Lost My Name, has created illustrated books based on more than 150,000 names.

More than a million copies of The Little Boy/Girl Who Lost His/Her Name have sold in 160 countries this year, including about 370,000 in the United States.

"It's an old-fashioned book, but with a lot of technology behind it," said Mr Sharabi, a 42-year-old former marketing consultant.

Since the codex format was invented more than 1,900 years ago as an alternative to the scroll, printed books have not evolved much as a creative medium.

Most of the technological advances in publishing have been digital, as publishers and app designers experiment with e-books that are enhanced with videos, music and other interactive elements.

But print is starting to get a high-tech makeover too, as more tech start-ups seek a toehold in publishing and on-demand technology gets faster, cheaper and better.

Lost My Name has carved an unusual niche within children's publishing.

Instead of relying on audio and visual bells and whistles to engage children, Lost My Name aims to make the narrative more captivating, by using computer codes to weave personal details into the storyline.

Personalised books have been around for decades. The early versions were little more than do-it-yourself scrapbooks with blank spaces where children could write in their names and paste pictures.

Since then, the medium has evolved, as major publishers, authors and children's entertainment companies dabble in personalisation in hopes of extending their brands.

In 2013, independent publisher Sourcebooks created Put Me In The Story, a line of personalised children's titles based on beloved brands and characters such as Elmo, Hello Kitty, those from Peanuts and Lemony Snicket.

Its top-selling personalised title, Marianne Richmond's I Love You So, has sold more than 100,000 copies.

Customised books remain a tiny part of the booming children's book business. Such titles cannot be mass produced and stocked in stores, where the majority of children's books are purchased (about 60 per cent, according to Nielsen).

And while some publishers and educators say personalised books help keep young readers engaged with print in an era of multiplying digital distractions, others are sceptical.

Reading is an essential way children learn to empathise with others and adopt someone else's perspective, and some warn that self-referential books could undermine that.

Still, some see the success of Lost My Name as evidence of a growing market for more creative personalised books.

Mr Thad McIlroy, a digital publishing analyst, said: "One of the things that's setting them apart from the competition is the high- quality visuals and the text. It's imaginative and beautifully executed."

Last autumn, Lost My Name released its second customised book, The Incredible Intergalactic Journey Home, geared towards children aged four to eight.

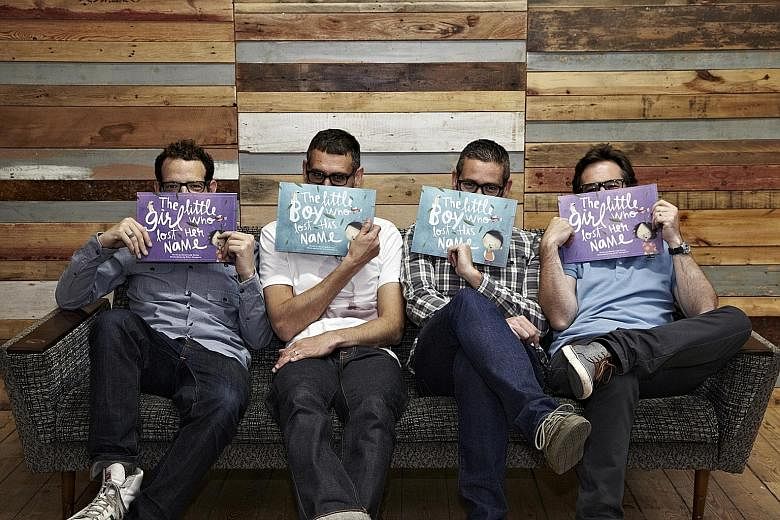

The company, which began with Mr Sharabi, Mr Oron, writer David Cadji-Newby and illustrator Pedro Serapicos, now has 70 employees, including 30 programmers, in its office in east London.

This summer, it raised US$9 million (S$12.7 million) from venture capital firms, including Google Ventures.

Looking back, Mr Sharabi said, he realised that none of this would have happened if he had not received that uninspired personalised book for his daughter.

"I will forever be grateful to my brother-in-law for bringing me this mediocre book," he said.

NEW YORK TIMES