Some keep the Sabbath going to Church - I keep it, staying at Home - With a Bobolink for a Chorister - And an Orchard, for a Dome - Emily Dickinson

That orchard was real: a medley of apple, pear, plum and cherry trees tended by the Dickinson family during their lifetimes. Over the decades, subsequent owners of the Dickinson house, known as the Homestead, removed the orchard, replaced extensive flower and vegetable gardens with lawn, and even installed a tennis court; and a devastating hurricane in 1938 damaged the grounds.

This year, however, the Emily Dickinson Museum has brought the poet's beloved orchard back to life, planting a small grove of heirloom apples and pears grown by the Dickinsons - Baldwins, Westfield Seek-No-Furthers, Winter Nelis - on a sunny corner of the property near Triangle Street in Amherst, Massachusetts.

The resurrected orchard is the latest development in a long-standing effort to return the Dickinson estate to its 19th-century splendour. Excavations of the grounds surrounding the house have been conducted for several years and will resume this summer.

Last summer, as the purple- tipped spears of irises unsheathed themselves and nasturtiums flaunted trumpets of fire, archaeologists excavated another one of Dickinson's gardens near the southeastern corner of the house.

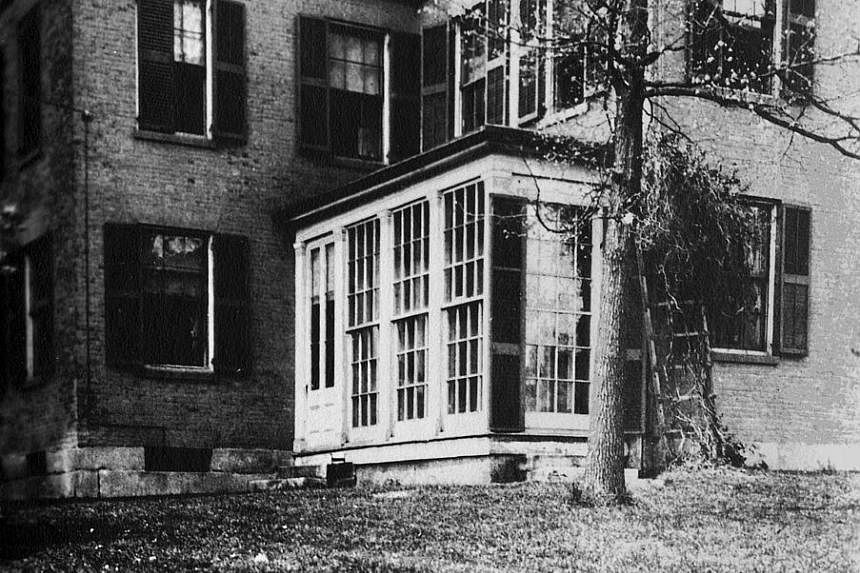

Over the past two years, the team has uncovered and analysed the foundation of what was once a small conservatory. Records show that Edward Dickinson built the greenhouse in 1855 for his daughters Emily and Lavinia. Emily transformed the long-windowed room into a year-round garden where ferns unfurled their feathers, the perfumes of gardenias and jasmine sweetened the air, and fuchsia, carnations and "inland buttercups" bloomed alongside "heliotropes by the aprons full".

Home owners tore it down in 1916 - 30 years after the poet died on May 15, 1886.

Now, the Emily Dickinson Museum, which consists primarily of the Homestead and the Evergreens, the neighbouring home of Emily's brother and sister-in-law, is preparing to restore the conservatory, plants and all. If all goes as planned, it will finish rebuilding the greenhouse, using as many of the original materials as possible, by the end of the year.

Dickinson was an amateur naturalist and a renowned gardener with a considerable knowledge of botany. "During her lifetime, Emily Dickinson was known more widely as a gardener, perhaps, than as a poet," the literary scholar Judith Farr wrote in The Gardens Of Emily Dickinson. But her two chief vocations were inextricable: Her passion for all things botanical is essential for a complete understanding of her personality, spirituality and verse.

"It's about trying to understand what her personal, physical world was like, juxtaposed to her immense universe of thought and imagination," said Ms Jane Wald, the executive director of the museum. "All that creativity and keen observation happened right here. Her home and gardens - these places were her poetic laboratory."

From her 30s onwards, Dickinson spent most of her time in and around her family's sizeable property, where she could wander over several acres of meadow, admire pines, oaks and elms, and help tend the orchard.

Ms Martha Dickinson Bianchi, her niece, recalled grape trellises, honeysuckle arbors, a summer house thatched with roses, and long flower beds with "a mass of meandering blooms" - daffodils, hyacinths, chrysanthemums, marigolds, peonies, bleeding heart and lilies, depending on the season.

The Dickinsons also grew Greville roses, which open with a shout of purple and fade to a whisper of pink, and cinnamon or love-for-a-day roses, which "flare and fall between sunrise and sunset", according to Ms Bianchi.

Her expertise in botany and gardening profoundly shaped her poetry. As Ms Farr wrote, her gardens "often provided her with the narratives, tropes, and imagery she required".

In her 1,789 poems, she refers to plants nearly 600 times and names more than 80 varieties, sometimes by genus or species.

In her more than 350 references to flowers, the rose is most frequent, but she was also fond of humble plants such as dandelions, clover and daisies. She used the latter two as symbols for herself in letters and poems. "The career of flowers differs from ours only in inaudibleness," she wrote. "I feel more reverence as I grow for these mute creatures whose suspense or transport may surpass our own."

By age 38, she stopped attending church, in part because she had found her personal Eden in her gardens. The resurgence of her garden each spring seemed to have buoyed her belief in the possibility of eternal life.

"Those not live yet/ Who doubt to live again-" she wrote seven years before her death.

The archaelogists plan to excavate nearby regions of the Dickinsons' lawn, searching for indications of old planting beds.

"There may even be leftover seeds or other botanical evidence," archaelogist Kerry Lynch said.

That raises an exciting possibility: that, much like the fascicles of poetry Dickinson secreted away in her room, organic fragments of the poet's gardens may have survived this whole time, just waiting for someone to find them and give them new life.

NEW YORK TIMES