-

Sept 28 session fully booked

There is strong support for The Big Read Meet on Sept 28, which will feature the book, A Chance Of A Lifetime: Lee Kuan Yew And The Physical Transformation Of Singapore.

To date, 102 readers have signed up for it. As the venue can take only 100 comfortably, registration is closed.

Two members of its editorial team, Ms Joanna Tan and former The Straits Times journalist Koh Buck Song, will join senior writer Cheong Suk-Wai in taking your questions and comments on the book, which shows how deeply the late Mr Lee cared about - and worked for - the safety, comfort and quality of life of his fellow Singaporeans.

If you have signed up for it, the National Library Board (NLB) has advised that you come early. The session kicks off at 6.30pm in the Multi-purpose Room of the Central Public Library, Basement 1, NLB headquarters at 100 Victoria Street.

Mao Zedong's rain of hell

The third book in Frank Dikotter's trilogy traces how the Chinese leader's jealousy of Nikita Khrushchev, who succeeded Mao's mentor Joseph Stalin, led to the Cultural Revolution

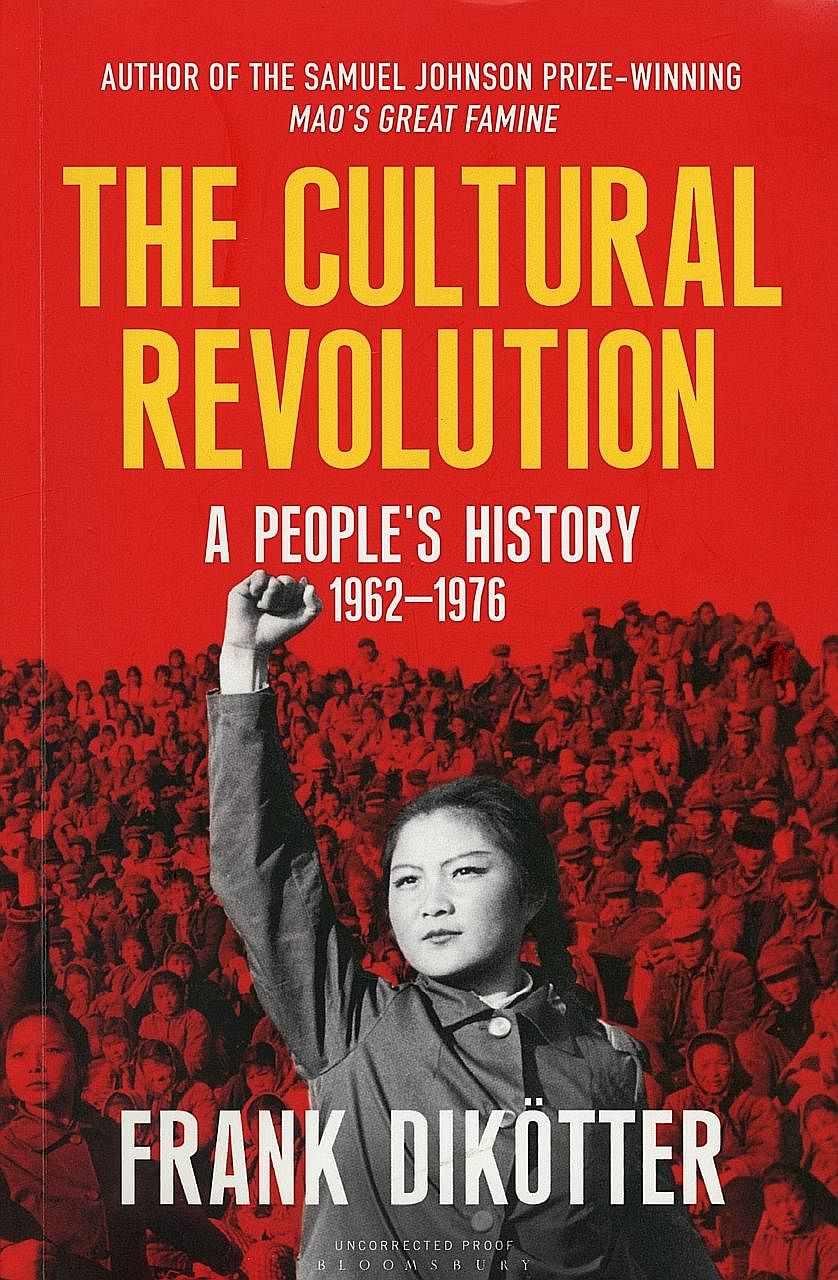

THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION: A PEOPLE'S HISTORY - 1962-1976 By Frank Dikotter

Bloomsbury/Paperback/382 pages/ $37.40 with GST from leading bookstores or on loan from the National Library Board under the call number English 951.056 DIK

Forty years ago this month, Mao Zedong, founder of the People's Republic of China (PRC), died at the ripe old age of 82.

By then, his rapacity for power and intolerance of rivals such as his defence chief Lin Biao, had led to hundreds of thousands of his countrymen being slain in the nationwide civil war he started, known as the Cultural Revolution.

The revolution, really Mao's concerted movement to purge all who did not agree with him, began proper in June 1966, but the Hong Kong-based Dutch historian Frank Dikotter begins his clear, absorbing book much earlier, in 1956.

The roots of Mao's rain of hell on his people, bourgeoisie and proletarian alike, were in his jealousy of Nikita Khrushchev, who succeeded Mao's mentor Joseph Stalin in 1953.

By 1956, Khrushchev had begun turning away from the class- levelling planned economy towards capitalism, which was a slap in the face for Mao, whose mandate was anchored in controlling who would produce what and when.

If Khrushchev's brand of capitalism prevailed, where would Mao be?

Thus threatened, Mao, who was intent on becoming the undisputed leader of the Red world, choose anarchy and mass murder to entrench his hold.

He began by goading his countrymen to "let a hundred flowers bloom" or be open about what they thought of their lot under him. They responded by protesting hotly against communist rule.

Edged into a corner of his own making, he proceeded to clamp down on them brutally, deploying students, and then industrial workers, to unleash fresh carnage on teachers, artists and anyone else to whom morals and culture were dear. He confounded his countrymen by confusing them all the time, blowing hot and cold whenever it suited him, consorting with rising leaders and then cutting them at the knees whenever they outshone him. The revolution wound down only after Lin's death in a crashed plane piloted by a Mao loyalist in 1971; a year later, Mao had a stroke and his prime minister Zhou Enlai had cancer.

When Zhou died in January 1976, and Mao in September that same year, the worst of the revolution was behind them.

Dikotter argues that most ordinary folk survived it largely by refusing to do as Mao told them and, instead, relied on their entrepreneurial nous to stay ahead of Mao's thugs. So, Dikotter notes in ample examples, it would be wrong to think that China's unchecked money-spinning and relative prosperity today was thanks to Deng Xiaoping.

This book is the third in a trilogy which began with Mao's Great Famine, Dikotter's account of Mao's blinkered collectivisation policies that resulted in an estimated 45 million Chinese starving to death. While Dikotter's is not a familiar name in literary circles, he is not without note. Mao's Great Famine won the prestigious Samuel Johnson book prize for non-fiction in 2011.

The second book in the trilogy, The Tragedy Of Liberation, traces the early years of communist rule.

In an interview with The Sunday Times last Wednesday, Dikotter said that before 2008, when the PRC began declassifying documents on the revolution, he could not have written this book.

"Imagine what it would be like to write about North Korea when the archives are completely closed up. It means that you can go only to Moscow or Germany to see what was written about Kim Il Sung and the history of North Korea."

When China did open up its archives just before the 2008 Beijing Olympics, he was "in there like a ferret" because he had learnt too well how quickly the Russians closed their hidden archives after opening it to the public when the Soviet Union collapsed.

What was still inaccessible to him, he said, were the day-to-day accounts and records of Mao's "direct entourage", including his wife Jiang Qing and her Cultural Revolution Group. "They are in the Central Archives in Beijing, but remain closed off to researchers."

No matter. Dikotter's gliding narrative is a model of how to make the best of what one has at hand.

FIVE QUESTIONS THIS BOOK ANSWERS

1 How did China go from rejecting capitalism to embracing it within 20 years?

2 Why can't the late Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping take most of the credit for its economic transformation?

3 Why did People's Republic of China founder Mao Zedong pit his supporters against one another so flagrantly?

4 How did the ordinary folk of China prove to be their country's salvation?

5 How has the Communist Party of China dealt with the seamier aspects of its oft-fraught history?

Just a minute

THE GOOD

1. Dutch historian Frank Dikotter, who is a history professor at the University of Hong Kong, has shown the way for fellow chroniclers to marshal what is oft-unwieldy research into an ordered, riveting read. His approach to the Cultural Revolution has been first to give readers the big picture on it, followed by a punchy chronology of how the revolution unravelled, culminating in a narrative that fleshes out each blow.

2. Dikotter was schooled in the French maxim, "If you think clearly, you will write clearly", and it shows. He is an elegant, economical writer, displaying in fast-flowing prose the prowess of one in command of his subject. There is also discernible balance, warmth even, in his tone, such as when he tries to help readers understand the peccadillos and likely motivations of such icons of cruelty as Joseph Stalin and Mao Zedong. Here he is, for instance, on the relationship between the two: "Ever since the death of Stalin in 1953, Mao had wished to claim leadership of the socialist camp. Even during Stalin's lifetime, Mao had considered himself a more accomplished revolutionary. It was he who had brought a quarter of humanity into the socialist camp in 1949."

THE BAD

1. This book is bereft of any visual element, not even a mugshot of Dikotter. Powerful as his storytelling is, people prefer lingering over images than words, and even diehard readers would appreciate photographs and maps to help them breathe amid his intense narrative.

THE IFFY

1. In describing the horrors which the misanthropic Red Guards visited upon China's upper classes, Dikotter takes a few leaves out of earlier memoirs of The Cultural Revolution, notably Nien Cheng's Life And Death In Shanghai, Jung Chang's Wild Swans and Gao Yuan's Being Red: A Chronicle Of The Cultural Revolution. In fact, he quotes them directly in his book. Reading him might have been a far more valuable experience if he had compared the accounts he found in recently declassified documents with theirs and gave his take on the subject.

Fact File: Lost sleep trying to write well

On a hot, humid summer's day about five years ago, Dutch historian Frank Dikotter walked into a provincial government archive in China. His aim? To dig up fresh information on the country's devastating Cultural Revolution, from the late 1960s to the mid-1970s.

Recalling the moment over the telephone last Wednesday, Professor Dikotter, who writes and speaks Chinese fluently, said: "There was an elderly woman in charge and I told her that I wanted to work on the period between 1962 and 1976.

"She said, 'Young man, you must understand that during that period, we had a Cultural Revolution... There was a lot of turmoil, so I cannot guarantee that we have complete archives. But we will do our very best to help you.'"

Prof Dikotter, who is now 54 and teaches history at the University of Hong Kong, thanked her deeply.

"I thought she was going to tell me off and say, 'You can't read everything on the Cultural Revolution.' But not at all; she was very helpful," he recalled.

"China's archivists are generally extremely professional and they will do their best to help you. But I'm not sure they were secretly feeding me documents that I shouldn't be reading."

But surely there were archivists who turned him away or tried to hinder his research? After all, even after 50 years, the brutal revolution is still something too raw for most Chinese to talk about.

Noting that archives existed in every city, country and province of China, he said: "I'm not saying it was without difficulty that I managed to read this material. But when someone tells you that the documentation is not open to outsiders or when you realise that the material you're being given is actually not very good, you just move on, go somewhere else. You do have to be persistent."

Such persistence had paid off for him. In 2011, he won the prestigious Samuel Johnson Prize for non- fiction, for his book Mao's Great Famine, an account of the mass starvation of an estimated 45 million people in the 1950s under Mao.

That success, he admitted in this interview, made it even more difficult for him to write The Cultural Revolution, the third in a trilogy which began with his prize- winning book.

He said: "You think, 'Oh my god, will I be able to do the same thing again? Will I be as good?'

"Before I started writing The Cultural Revolution in the summer of 2014, I became so panicky. I lost so much sleep worrying about it that I just thought, 'Well, the only way to confront my worries was to sit down and start writing.'

"And the moment I put pen to paper and had 1,000 words on the first day, I felt, 'This was going okay. I could actually do this.'"

Such self-doubt is humbling when you consider that he has been a scholar of modern China for the last 30 years. It was his first love, 19th-century Russian literature - particularly the work of Fyodor Dostoyevsky - that led to his passion for the history of China.

Born in the Netherlands, his father's work at the Dutch State Mines took his family around the world.

As an undergraduate at the University of Geneva, the young Dikotter studied Russian and Chinese. When he learnt that access to the Soviet Union's literary archives was nigh impossible then, his Chinese teacher suggested that he visit China and delve into its archives on Russia instead.

He never looked back.

From 1985 to 1986, he travelled around China, with Nankai University in Tianjin as his base. There were so few foreigners there then, he recalled, that a postcard from his Canadian friend, addressed simply to "Frank from Holland", reached him in good time because in Tianjin then, there were only about 100 foreign students, 10 among whom were Dutch and, among them, there was "only one Frank".

He moved to Hong Kong 11 years ago with his British wife, retired lawyer Gail Burrowes, to immerse himself even more in the ways of China - and, of course, to be closer to its archives, which he said had been gradually declassified since the mid-1990s.

It helped, he added, that his two stepsons were already grown up then and he and his wife had driven the younger of the two to university in Wales shortly before the couple upped sticks for balmier Hong Kong.

He said: "It was the absolute perfect moment in terms of timing. We were free and ready for a new challenge."

Join ST's Telegram channel and get the latest breaking news delivered to you.

A version of this article appeared in the print edition of The Sunday Times on September 18, 2016, with the headline Mao Zedong's rain of hell . Subscribe