Twice, Indonesian writer and activist Goenawan Mohamad's Tempo magazine was temporarily banned after its articles drew the government's ire.

But writing, he insists, need not crumble under the threat of censorship.

"When you live under censorship and you know you have to survive, at the same time, you have to hold on to your principles. You know that you're scared, but don't succumb. Don't justify the oppression," he says.

"You have to negotiate the space... You attack when the enemy is weak and withdraw when the enemy is strong. And the government is not always strong, not always unified, and that's what you have to discern... Then you attack and you fight."

Still, Goenawan, a fierce critic of former Indonesia president Suharto, who clung on to power for three turbulent decades stained by bloodshed and corruption, adds wryly: "At the end, you might even fail. That's why we were banned twice."

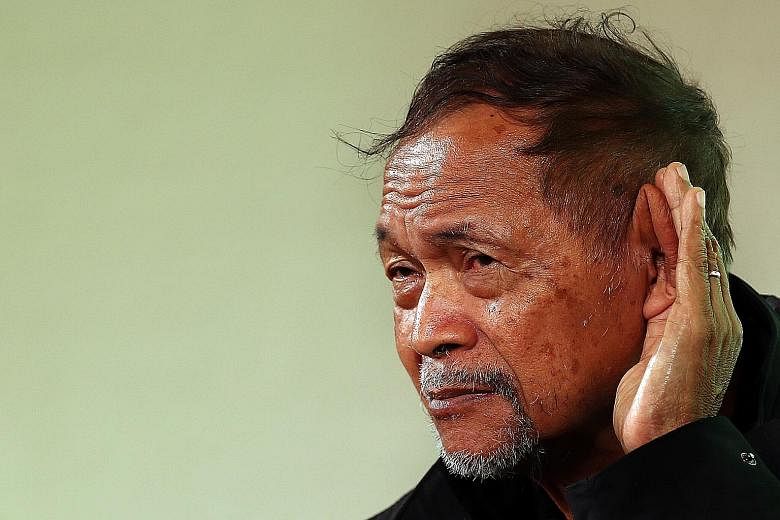

At his hour-long talk When Meaning Is Managed: The Fate Of Literature in Indonesia at the Singapore Writers Festival last Saturday, the 74-year-old charmed the 125-strong audience at The Arts House Chamber with his unwavering faith in the power of writing and his unexpected humour.

At first glance, he is unassuming: a narrow-shouldered gentleman scholar who speaks of Plato and Russian literature with ease and authority, half-vanished under a roomy black jacket. But when he speaks, there is a fire to him.

When the topic turns to writing in Indonesia, where language and the freedom of expression cannot shake off government scrutiny, Goenawan's first response is: "When I write, the first urge is to liberate the language."

He has, throughout his life, pushed for greater press freedom.

In 1971, Goenawan founded Tempo, a magazine inspired by American weekly Time, peddling non-partisan articles on issues ranging from politics to sports.

But its unflinching take on Indonesia set it on a collision course with the government: It was banned in 1982 over election coverage. The next run-in was in 1995 when an article criticising the government's move to purchase a fleet of East German warships was printed.

A few months after it was banned, the magazine moved online as Tempo Interaktif. The full magazine made a comeback only in May 1998, after Suharto's fall from power.

Taking the crowd on a whirlwind tour of Indonesia's political history, Goenawan explains how different regimes have had an impact on the way language in the country is managed.

First, came totalitarian rule under Indonesia's first president Sukarno, who Goenawan says sought to influence both public behaviour and private thought, "to indoctrinate and to brainwash".

Then, Indonesia came under Suharto and his bureaucratic, authoritarian regime, which focused its attention on influencing public behaviour but wasted no time on indoctrination.

In a moment of dark humour, Goenawan brings up Soviet leader Josef Stalin ordering the execution of Yiddish poets.

"In Indonesia, poetry survived, simply because the bureaucratic regime doesn't have time to read poems. To them, poetry is useless," he said. "But ah, that's the beauty of poetry."

Now, with Indonesia's foray into democracy, a commercialised, commodified system has taken root. One of the results of this system is the controlled messaging on television, he explains.

Even as he took on the bleak subject of censorship, Goenawan offered many light-hearted moments, eliciting chuckles out of the audience.

Pointing out that his Twitter account has more than 470,000 followers, Goenawan confesses his obsession with the site is driven by long hours on the road.

"I even give lectures on Marxism because of the traffic. Because in Jakarta, you have traffic (jams) for three hours!" he says to laughter.

Goenawan is well known for his essays, having penned more than 2,000 of them for his column Sidelines in Tempo magazine.

To moderator Peter Schoppert's question on whether he has been tempted to write a novel, he says: "My theory about novels in Indoesia is we cannot produce many novels because we don't have a long winter. The Russians do, that's why they produce all these long stories."

Sales manager Andrew Lau, 34, bought Goenawan's latest book Faith In Writing: Forty Years Of Essays after the talk.

Before leaving at a sprint, hoping to catch Goenawan for an autograph, he says: "I bought tickets to his talk on a whim, but I was really impressed with him. He has such a clear voice and perspective - and he was hilarious in person too."