The BMW private taxi shudders as it moves over the gritty unsealed road, its gleaming black body soon coated in loess dirt.

Fang, the mild-mannered driver whose car I picked from a small fleet of taxis outside the station - some battered Hyundais, a few European models that looked out of place in the rugged loess terrain - says he bought the sedan last month.

The station also looked too grand and modern a gesture in this ancient landscape, especially after the handful of travellers disappeared in a whirlwind gust into the surrounding country.

Fang is one of the enterprising millions who is swimming in the new money. He left his father's farm and went to Xi'an to work, before heeding the government's call to develop Fuxian. He has started up an electronics shop, while his wife runs a hairdressing salon in town. He nodded when I said "Du Fu Caotang" ( 草堂 , thatched hall), but now there is a flicker of doubt in his eyes.

On the left, the Hulu (gourd) River swings in a wide southward arc to Fuxian, where a regiment of new high rise stands like a foreign colony, its stark concrete and glass violating the Shaanxi browns and green. Later, walking through the eerily vacant new section of the town, I will see the solitary figure of the great poet on the boulevard between two dark-grey apartment blocks, looking a little annoyed at being placed in the midst of the stark reality of the new Middle Kingdom.

It took only three hours to get from Xi'an to Fuxian, or Fuzhou, as it was called during the Tang dynasty. The plains north of Xi'an slowly erupt into the folds of scrub-covered hills and gorges, narrow ravines that broaden into valleys before the mountains close in again.

The train passed through a series of tunnels, one so long that I wondered how Du Fu (AD712-770) overcame this formidable range. I was trying to plot his walk from Fengxiang (present-day Baoji, 180km west of Xi'an) to see his wife and children in Qiang Village in Fuzhou.

They had fled here after a nightmare trek from Fengxian, where Du Fu had left his family to try to get a court appointment in Changan, which turned out to be a lowly ranked, miserable commission.

Before starting his job, he had set out to see his family, passing the Huaqing Palace outside of Changan. He could hear the carousing Emperor Xuanzong in the arms of Consort Yang Guifei, while outside the vermilion walls, starving beggars latched onto putrid scraps being thrown out. The sorrow at his country's plight weighed heavier as he plodded through the famineravaged country, compounded by worry about his family.

His journey of about 120km is recorded in Five Hundred Words, My Journey From The Capital To Fengxian County, a tremendous poem that combines personal experience and history. You can hear the movement of his tired legs and feel from its rhythm the burden in his heart. There is one more mouth to feed - his wife has just given birth to his fifth child. He arrives to find that his infant son has died; his half-starved wife had been unable to nurse him.

Even as he arrived in Fengxian, the barbarian general An Lushan led his rebel troops in a march on Changan. The family fled to Fuzhou. Then Du Fu set out for Lingwu, where the court had regrouped under the new Emperor Suzong. He was captured on the way by the rebels and held in Changan for a year, before escaping and joining the court, now established at Fengxiang.

Rewarded with the position of Left Reminder for his loyalty, he did not take long to incur the Emperor's wrath. He took leave and headed for Fuzhou, a journey of 400km northeastwards, recounted in another poem Journey North. He saw razed villages, hundreds of sick and wounded; on a moonlit night, he stumbled on a carcass-strewn battlefield.

From the grime-encrusted carriage window, I pictured his tiny figure inching along the treacherous path above the river, crossing old stone bridges that were still standing, albeit in disrepair.

It is late spring, the apple, peach and walnut orchards on the hillsides have almost recovered from the devastating floods last year, the trees wearing a shimmering green and some already in bloom. Fang points out the tidemarks on the hills, where the river gouged out huge swaths of the friable earth last year.

The car squeezes past a couple of trucks loaded with bricks from the riverside kiln before we climb a narrow road, past an old man sitting on the mud-bank. Fang winds down his window and asks: "Where is Du Fu Caotang?"

The old man points his cane back down the road. His worried, thoughtful face and wispy beard remind me of an ink portrait of the poet by Jiang Zhaohe (1904-1986) .

Fang turns the car around and we head upriver to another village where, after an animated exchange with two old farmers, he does the same reverse manoeuvre and we are soon back at the first village. As the car climbs uphill, he points to a few stelae standing in a field to the right. Tang dynasty, he says, and winds down his window and spits out derisive words at the old man still sitting by the road.

He parks the car in front of an ancient pagoda tree. We follow the dirt path between humble bare-brick dwellings with the obligatory red couplets pasted on the doorjambs, some with cave houses at the back. There are cave houses all over Shaanxi - they are cool in summer and warm in winter.

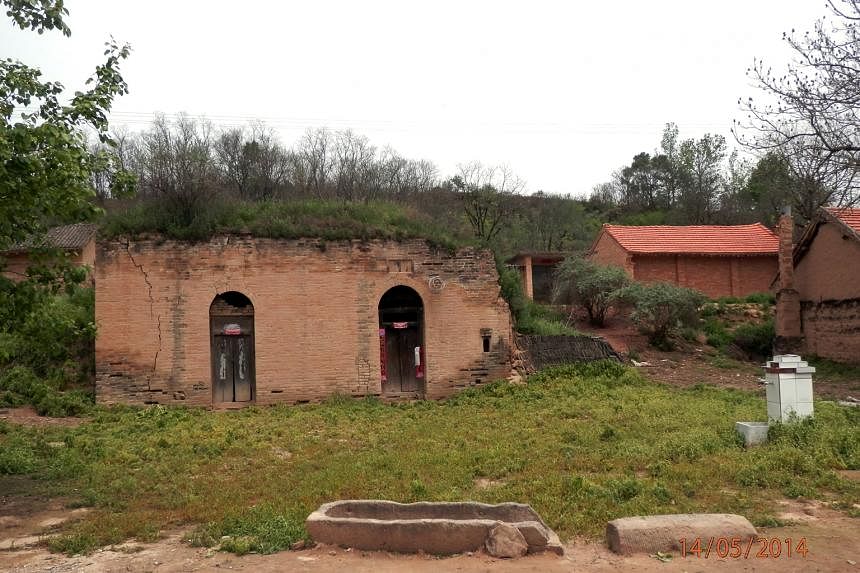

A woman with a baby slung on her back directs us to a clearing downslope. In front is a crumbling house, its roof smothered in earth and weeds. There are two padlocked doors lined with frayed couplets. Fang pulls himself up to the opening above the toprail, his sneakered feet scrabbling against the worn wooden door. He gestures for me to do the same. I leap, grip the dusty toprail and peer in. In the dim cool light, I can make out a desk, a kang bed and a stove, all covered in thick dust; the smokedarkened walls are plastered with faded, peeling newspapers.

I imagine Du Fu's wife and children huddled in there, waiting for news from the father-husband, unsure of his fate. They were half-starved like all the other laobaixin (commoners). Journey North ends with Du Fu arriving and finding his wife and children in clothes "patched over a hundred times", his daughters' dresses barely covering their knees, his barefoot son turning his face to hide his tears. The family's reunion is also vividly recorded in his poem Qiang Village:

Over the wall the neighbours look on,

all sighing and sobbing.

Into the night we hold the candles

to look at each other as in a dream.

There is no sign that the poet or his family were ever here. In this simple village that seems to have escaped the winds of change sweeping through the town, there is no memorial hall, statue or stela.

Wherever the poet made a significant sojourn, a caotang was erected. In Chengdu, the humble thatched cottage that he built has turned into a sprawling theme park. In Duling, a hamlet just south of Xi'an, where Du Fu sojourned briefly, the caotang that was rundown when I first visited is now spruced up, the broken statue of the poet sheathed in plastic, presumably for restoration.

In remote Tonggu, there is now a caotang with a panoply of stelae and tablets inscribed with his poems. In his birthplace Gongyi, the caotang complex fans out from the cave-house where Du Fu was born.

In Changsha, there is a memorial hall overlooking Xiang River, on which waters the poet ended his last years. I wonder about the authenticity of these sites but, like a good pilgrim, I surrender to the hagiographic spirit.

This abandoned abode may not be the place where the poet's family sheltered. But local knowledge is good enough and so my quest ends here.

I have retraced his journey in my mind for eight years now, since starting on a novel about China's greatest poet. It was begun around the time I started writing poetry again, after a long silence that followed my migration to Australia.

Maybe it was homesickness that led me to Du Fu. Reading him again after so many years of not reading Chinese gave me a sense of homecoming and it comforted me to find a tutelary spirit whose poetry was driven by a quest for home and peace.

Dutifully, I take pictures. Fang lets me stand on his clasped hands to photograph the interior. Then we drive back down the slope. I wave to the poet's double, who smiles knowingly. The car sails down the tarmac road to Fuxian, its developments unfolding under the watchful eye of a hilltop Tang pagoda across the river, its silhouette now blurred in a blizzard of dancing catkins.

• Boey Kim Cheng was born in 1965 and emigrated from Singapore to Australia in 1997. He taught at the University of Newcastle for 13 years before joining Nanyang Technological University this year. He has published five collections of poetry and a travel memoir Between Stations.

More Reading Special stories here.