Book Of The Month

Doorway to a past

Canadian-Chinese novelist Madeleine Thien gives a consummate portrayal of the lives of individuals caught up in tumultuous events in 20th-century China

FICTION

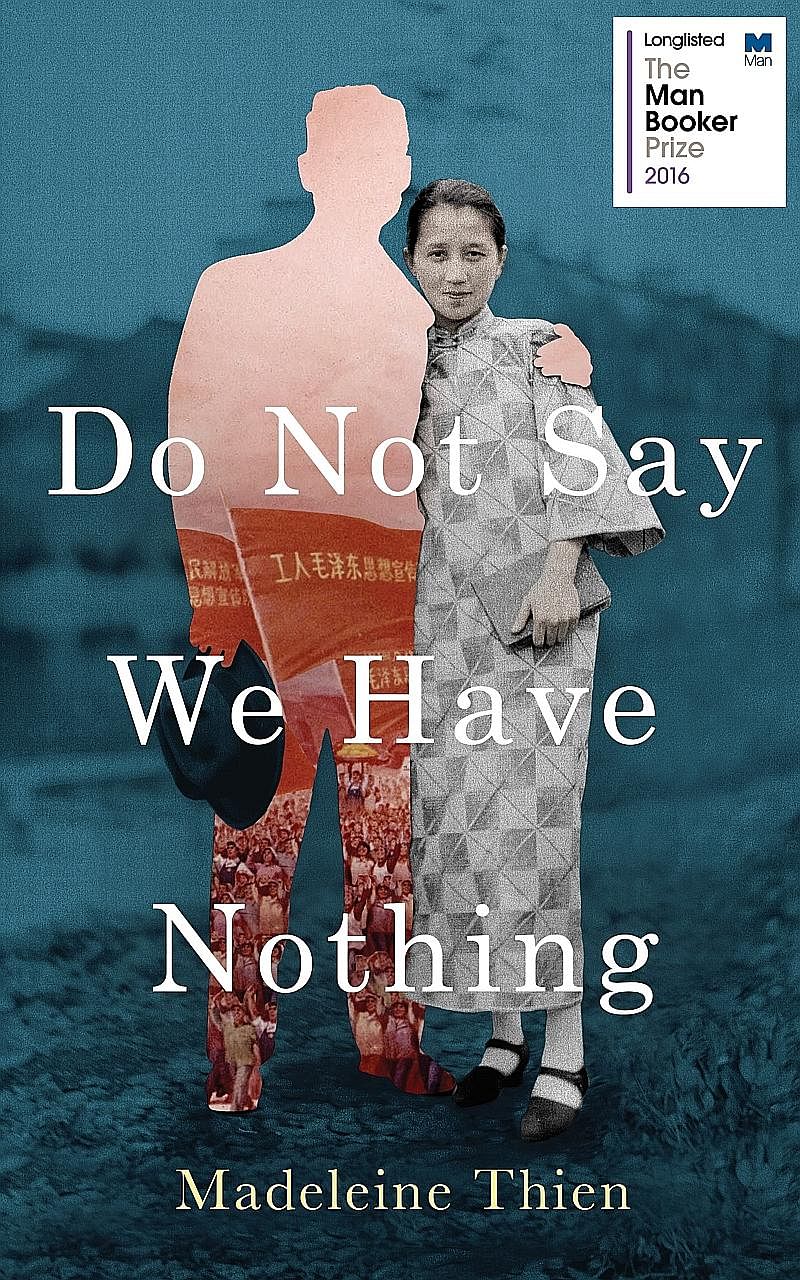

DO NOT SAY WE HAVE NOTHING By Madeleine Thien

Granta/ Paperback/ 463 pages/ $32/ Major bookstores/ 5 stars

As this powerful and moving novel draws to a close, one of the main characters, Ai-ming, a young woman who left China after her involvement in the Tiananmen student demonstrations, reflects on the enduring, myriad presence of the past through storytelling: "It is a simple thing to write a book. Simpler, too, when the book already exists, and has been passed from person to person, in different versions, permutations and variations. No one person can tell a story this large…"

The word "simple" is striking, for what the author of Do Not Say We Have Nothing has achieved is not at all simple.

Canadian-Chinese novelist Madeleine Thien exceeds all expectations in her consummate, sensitive and nuanced portrayal of the lives of individuals caught up in the tumultuous events spanning 50 years in 20th-century China.

The novel has been longlisted for the prestigious 2016 Man Booker Prize.

It begins with the arrival of 19-year-old Ai-ming in Canada, where she meets Marie, the 11-year-old daughter of Jiang Kai, a close friend of her father Sparrow since the 1960s, when they met at the Shanghai Conservatory of Music. Jiang Kai was a talented pianist and Sparrow's student. Ai-ming and Marie do not speak about the deaths of their fathers, of Jiang Kai's jump off the ninth storey of a building in Hong Kong after Sparrow died in Beijing during the military clampdown triggered by the democracy movement at Tiananmen Square.

They speak, instead, about a Book Of Records, a mysterious anonymous Chinese novel at once ageless and post-modern, a hybrid work of fiction, history and secret codes, disseminated across the country, surviving war, censorship and all imaginable forms of oppression through notebook copies made by hand.

There is a beautiful conceit at work, one suspects, in the parallel that might be drawn between Thien's novel and the Book Of Records.

What is this novel if not a book of records, an interwoven collection of narratives told by individuals who have witnessed terrible, unspeakable injustices and sorrows?

The Book Of Records comprises 31 chapters, although in the novel, it is never recounted from start to end, making its appearance rather in the form of loose, individual chapters copied into notebooks.

When Marie is shown one of these notebooks for the first time, she describes it as "tall and narrow, the dimensions of a miniature door".

The analogy is significant. Throughout the novel, the stories in the Book Of Records are a source of fascination and obsession because they act as a means of escape, a portal to freedom.

Similarly, the rich inner lives of Thien's characters provide much- needed relief from her clear-eyed retelling of horrific, abhorrent acts of violence and destruction that were committed in China, the loss of innocent lives, the break-up of families, the senseless dashing of the hopes of the young and the peace of the old.

There is deftness and grounded humanity in the way Thien has brought her characters to life, especially the vulnerability of Sparrow's cousin Zhuli, a violin prodigy besotted with Prokofiev at a time when love of Western classical music was a punishable offence; the beauty of Sparrow's re-awakening in middle age after he allows himself to act on his forbidden loves, for Jiang Kai and composing; and the resilience of Big Mother Knife, Ai-ming's quick-thinking, hot-tempered and foul-mouthed grandmother with a baby-soft heart.

The 19th-century writer and scholar Walter Pater famously wrote that all art aspires to the condition of music.

Music, the vocation and livelihood of most of Thien's characters, is also present in the novel's artfulness. The question of how literature aspires to the condition of music is answered splendidly in her book.

The voices of different generations come together in the same chapter like different polyphonic threads. The structure of the novel also reminds one of the sonata form, where themes and ideas are introduced and re-appear in further developed shapes.

In a recent interview, Thien was asked if the subjects she had chosen to write about had ever frightened her. (Her last novel, Dogs At The Perimeter, centres on a survivor of the Khmer Rouge.)

Thien replied that art draws people's attention to ugly truths by "scrap(ing) up against those ugly places and conced(ing) their existence. Which is very different from performing, fetishising or objectifying that ugliness, resulting in something closer, along the spectrum, to spectacle rather than art".

This is a timely reminder of the unique way in which literature works on people to broaden their awareness and deepen their understanding of history, politics, culture. The engagement of literature with the world takes place through subject as well as form.

Its value lies in its mirroring of life; this mirror reflection owes its affect and persuasion to the writer's love of language and the power of his or her imagination. A spreadsheet of issues will not make a convincing mirror image of life.

If you like this, read: The Vagrants by Yiyun Li (Random House, 2010, $25.62, Books Kinokuniya and other major bookstores). Set in China during the late 1970s, the novel follows a group of ordinary people whose lives are dramatically changed by the political upheaval of the Democratic Wall Movement, a pro-democracy anti-communist groundswell that was harbinger to the uprising at Tiananmen Square.

FICTION

HOT MILK By Deborah Levy

Penguin Books/208 pages/Paperback/$29.91/ Major bookstores/ 3 stars

Hot Milk, the latest novel by British author Deborah Levy, reads like a hazy, drug-induced dream, the fraught relationships between its eccentric characters interwoven with layers of rich, concealed meaning and Greek mythological imagery.

It has been longlisted for the United Kingdom's prestigious Man Booker literary prize this year and is likely to follow in the stead of Levy's Swimming Home, which was on the 2012 Man Booker shortlist.

A pity then that the new book's potential is never fully realised. Levy is a sensuous writer adept at conjuring up gorgeous settings, but she struggles to contain the loopy plot, which vacillates between artfully absurd and downright bewildering.

The story starts promisingly, with anthropology graduate Sofia Papastergiadis chaperoning her hypochondriac mother Rose, who claims to have lost the use of her legs, to a clinic in southern Spain for treatment.

Ruminating on their relationship, she says: "I am my mother's burden. She is my creditor and I pay her with my legs. They are always running around for her."

Hot Milk is at its most potent when it scrutinises this vital yet impossible relationship, laced at once with resentment, deceit and betrayal, with love and familial obligation tucked away somewhere deep inside.

Readers will relate to how the wheelchair-bound Rose orders Sofia to drive them around while deriding her technique and makes her wait on her hand and foot.

Sofia, in quiet rebellion, retaliates by being hypercritical of Rose, psycho-analysing her ("She more or less inhabited a building called Grievance Heights") and, at one point, wheeling her to a road and abandoning her there.

Equally fascinating and toxic is Sofia's ambivalent dalliance with her German fling Ingrid, with a "body long and hard like an autobahn", who goads her into vying for her affections with another man.

The love-hate nature of Sofia's relationships is also mirrored in her inexplicable attraction to the medusa jellyfish that dot the waters off the Mediterranean coast - she dives into their midst repeatedly, despite the stings and welts they give her.

Levy is a skilful scene-setter - much of her story unfolds like a febrile nightmare, often shifting between the arid Andalusian deserts and the "warm, oily" Mediterranean sea teeming with jellyfish.

She also adds a touch of sinister urgency by frequently alluding to the looming Greek debt crisis, which threatens to submerge Europe in economic turmoil.

But whereas Levy fashioned a tight, gripping narrative around an interloper who disrupts a summer holiday in Swimming Home, she displays little of that control here.

The book is bogged down by an excess of loose, jarring story threads, such as a ploy by some locals in Almeria to expose the clinic's doctor as a charlatan, an Alsatian that won't stop barking and a truly bizarre post-coital scene in which Ingrid beheads a snake.

A reader can barely parse the significance of one event before another comes along.

At one point in the book, Sofia hopes to "mess up the story I have been told about myself. To hold the story upside down by its tail". Levy has certainly done that with Hot Milk, but not in a good way.

If you like this, read: My Name Is Lucy Barton by Elizabeth Strout (Penguin, $17.21, Books Kinokuniya), a far more digestible and riveting narrative centred on a woman who lies in hospital after surgery and reunites with her estranged mother. It is also on this year's Man Booker longlist.

Lee Jian Xuan

FICTION

ELEVEN HOURS By Pamela Erens

Tin House Books/Paperback/165 pages/$27.89/ Books Kinokuniya/ 3.5 stars

In the 11 hours it takes to deliver a baby, the parallel stories of two women unfold. New Yorker Lore is composed and as prepared as a woman can be for labour, with a comprehensive and instructional birth plan. Franckline, her Haitian midwife, is drawn to the mysteries of childbirth even before she reached adolescence.

Pamela Erens condenses these 11 hours into a novel of the same name, a slim but compelling 165-page read that offers a window to the events that have led to their meeting in the delivery ward.

"A story I will never fully hear, even if she offers it to me," thinks Franckline, "and it's the body that concerns us here today."

Franckline is right. The insistent rhythms of Lore's labour take centre stage and Erens, who has also authored The Virgins and The Understory, is unflinching in her descriptions.

"A good universe could not include the forcing of her child half inch by half inch down the birth canal, its soft head squeezed misshapen by the hugging walls; could not include her own grotesque and agonised prying-open," muses Lore between contractions.

Erens describes them all with a growing intensity, bringing home the gruelling yet infinitely rewarding experience of human creation, a shared experience that bonds women around the world. Indeed, as her contractions grow more frequent, Lore is forced to lower her prickly defences and rely on Franckline, clutching the midwife's smaller frame, smelling the "subtle, spicy odour" of her skin.

The physical intimacy of the two women is mirrored by their maternal journeys, a longing for their unborn children, for Franckline is pregnant as well and this is one of the many revelations that unfold during these 11 hours. Bit by bit we learn about the two women; inch by inch the baby crowns.

As she reveals her two protagonists, Erens alternates between Lore and Franckline's perspectives, though never in a confusing way, just an easy slipping between two women who have both experienced their own versions of loss, betrayal and heartbreak.

To this end, Erens is light-handed with the details, leaving out the minutiae essential for character development. Consequently the supporting cast - Franckline's husband, who longs for a child; Lore's former partner Asa and her best friend Julia - are less fleshed out.

But they will not matter in the last quarter of the novel as Lore's carefully detailed birth plan disintegrates in a race against time. The suspense finally boils over in Eleven Hours' breathtaking conclusion, a gripping and unlikely reminder of the miracle that is childbirth.

If you like this, read: Little Labours by Rivka Galchen (New Directions, 2014, $17.53, Books Kinokuniya), a short book of essays on babies in various cultures.

Clara Lock

FICTION

AUGUSTOWN By Kei Miller

Orion Publishing/Hardback/223 pages/$27.97/ Books Kinokuniya/ 4 stars

The story of the fictional valley Augustown comes together in a tapestry of tales from the past and present, of the privileged and downtrodden, in a narrative that straddles the line between the real and mythical.

Augustown bears an uncanny resemblance to the real August Town in Jamaica, which was said to receive its name as freedom came to the enslaved people on Aug 1, 1838.

In Augustown, six-year-old Kaia returns home from school, whimpering. His blind grandaunt Ma Taffy senses that something bad has happened and asks the boy if he has heard of the flying preacherman named Alexander Bedward (echoing real-life events in August Town, where there was a prophet with thousands of followers, also named Bedward, who proclaimed he was God and could fly).

Then reaching to touch Kaia's head, Ma Taffy discovers that a teacher had cut off the young Rastafarian's dreadlocks, setting in motion the events of April 11, 1982.

What could have seemed like an isolated incident is quickly given context through Ma Taffy's memories of another dreadlocked Rasta whose hair was cut by figures of authority.

He was a fruit and vegetable seller whose handcart and produce were also confiscated when he was arrested on a trumped-up charge.

He hanged himself soon after.

Each individual's tale adds a fresh perspective and vivid details to the big picture of the novel, building up to its final, dramatic reveal through a mix of tragic and hopeful moments.

From the mocking of preacher Bedward's followers, who came crashing down despite his prophecy that they would ascend to heaven, to the more optimistic tale of a young mother who studies for college with the help of her employer, readers will draw a slice of life of this valley and the complex flavours it has to offer.

As the narrator aptly points out at the start of the book, it is no exaggeration to say that every day contains all of history.

If you like this, read: A Brief History Of Seven Killings by Marlon James (Oneworld Publications, 2015, $19.80, Books Kinokuniya), which is about the attempted assassination of Bob Marley, telling the story of Jamaica in the 1970s and early 1980s.

Seow Bei Yi

FICTION

COMMONWEALTH By Ann Patchett

HarperCollins/Paperback/352 pages/$27.99/ Books Kinokuniya/ 3.5 stars

On a hot afternoon in 1964, a man and a woman share a gin-fuelled kiss away from the hustle and bustle of a christening party, the new baby caught between them.

The man is Bert Cousins, a deputy district attorney who has gatecrashed the party to escape his pregnant wife and their three demanding toddlers.

The woman is Beverly Keatings, the beautiful wife of a cop, taking a quick break from the party for her second daughter Franny.

With that one stolen kiss, Ann Patchett neatly sets the stage for her seventh novel: Bert and Beverly divorce their spouses for each other and the six children from their previous marriages become stepsiblings in an awkward blended family.

Forced to spend each summer together, they eke out an odd camaraderie built on their shared distaste for their parents, until a death shatters the truce.

Decades later, Franny - whose christening party sparked Bert's affair with her mother - takes up with Leo Posen, a famous American author.

Her childhood stories become fodder for his new novel, Commonwealth, which proves a resounding success.

With the intimate details of their family life now on unexpected display, Franny and her family have to deal with old wounds and re-examine their pasts and themselves.

Commonwealth is at its core a tale of the tangled web of family obligations and shifting allegiances over five decades as parents and children struggle to figure out their place in a family tree grown wild.

But with the added conceit of a novel within a novel, Patchett also explores family history: What memories do people share and what do they hide? Who has to consent?

In Patchett's hands, this dysfunctional extended family shines. Each member is richly imagined and realised, and Patchett's wry tone and keen eye for details make her descriptions of family life - even the mundane routines - a treat.

But her penchant for detail is also the book's downfall. It plods along in some parts and the scenes between Franny and Leo - the book's weakest character - can come across as interminable as the pair pick over the same conversation topics again and again.

Otherwise, Commonwealth is a meaty read and a complex, layered look at how families form and fray.

If you like this, read: Bel Canto by Ann Patchett (Harper Perennial, 2001, $28.21, Books Kinokuniya). In 1996, a group of radicals take hostage hundreds of high-level diplomats, officials and executives during a party at the official residence of the Japanese ambassador to Peru. Some of them are held for more than 100 days. Patchett seizes on this premise for her fourth novel and weaves a tense and - as relationships bloom between terrorist and hostage - surprisingly tender tale.

Nur Asyiqin Mohamad Salleh

FICTION

THE HOUSE AT THE EDGE OF NIGHT By Catherine Banner

Random House/Hardback/429 pages/$43.24/ Books Kinokuniya/ 3.5stars

When itinerant doctor Amedeo Esposito sets foot on the fictional southern Italian island of Castellamare, he knows at once this is where he is meant to be.

An indiscretion committed shortly after his arrival, however, forces him out of medical practice and into ownership of the bar in the novel's title.

Young adults fiction writer Catherine Banner's first novel for adults spans several generations of Espositos on the island.

Unlike other authors who use their characters to explore grander issues such as war or poverty, she does the opposite here. The problems of the outside world - such as the rise of fascism or the global financial crisis of 2008 - are transformed, becoming smaller when transported to Castellamare.

While the island has its own small band of fascist sympathisers, for instance, all the punishment they mete out to their communist adversaries is limited to seizing them and forcing them to drink a pint of castor oil.

As one of the island's elderly matrons puts it: "We've all got to live together after this, you know."

In contrast, small occurrences, seemingly of little consequence, are magnified and remembered for generations.

Amedeo's initial wrongdoings lead to the birth of his two sons from different mothers on the same night. These "twins... leaping into the world as though by agreement", go down in the island's history as a miracle.

This focus on the parochial is charmingly done and completely immerses the reader in Banner's sun-drenched Italian island with its fizzy limonata and deep-fried savoury rice balls.

Yet the novel conveys a sense of how transient human lives are as compared with the enduring bedrock of Castellamare.

Four generations of its inhabitants are born, grow and die in the blink of an eye and wild ideologies barely take root before being blown away.

In the end, all that remain are the things that belong to the island - not just the dank caves and cliffs of the physical landscape, but also the age-old ties between the villagers.

If you like this, read: One Hundred Years Of Solitude by Gabriel Garcia Marquez (Penguin, 2013 reprint, $20.18, Books Kinokuniya), which follows the story of the Buendia family over several generations. The novel, first published in 1967, is considered to be one of the Colombian author's greatest works.

Linette Lai

FICTION

BREAK IN CASE OF EMERGENCY By Jessica Winter

HarperCollins/Paperback/269 pages/$28.89/ Books Kinokuniya/ 3.5 stars

Jessica Winter, who has gone from movie reviewer at The Village Voice to editor jobs at Time and O: The Oprah Magazine and features editor at Slate, makes her debut as a novelist.

Unlike her, the heroine of her work, Break In Case Of Emergency, is not doing so well in the world of work. Jen is an artsy, highly educated New Yorker in her 30s who has given up a possible career as a painter for a stable income and health benefits. When she is laid off from a communications job at a non-profit, she finds a new one at another non-profit started by actress and rich divorcee Leora Infinitas.

But her ill-defined job at LIFt (Leora Infinitas Foundation), a vanity charity with the fuzzy goal of lifting women up, is a nightmare for Jen, who takes things too seriously, unlike her dryly funny colleague Daisy.

Jen, who is married to school teacher Jim, also has trouble conceiving.

There is no great climax in these pages, beyond the mystery of whether Jen will improve her situation.

Still, the book is a treat to read - many people spend so much of their lives at work, but there aren't many novels that look at the workplace.

At the risk of being politically incorrect, Winter pokes fun at an all-female workplace where the bagels and salmon at a meeting are "not a breakfast offering so much as a test of self-restraint".

And then there is the false bonhomie. An e-mail titled "Happiness!" from her direct boss Karina to Jen to say she's "thrilled" that Jen is coming on board and that they should lunch, does not lead to even a coffee a dozen e-mails later.

Winter also has fun with the obsession with acronyms, which Singapore readers may relate to well.

Among LIFt's schemes are Wise (Women Inspired for Self Education), Wish (Women's Initiative for Sleep Hygiene) and Well (Women Empowered to Love their Libido).

Winter is adroit at satirising the idiosyncrasies of the workplace, though it is sometimes hard to get into the book given its occasional excursions into Jen's mind.

("Jen identified the physiological components of pleasure, satisfaction, and joyful anticipation whirling into kaleidoscopic coordination with one another before just as quickly spinning away, their limbic messaging scrambled by a sharp retort from Jen's prefrontal lobes...")

The novel may also be too diffuse in its aims. On top of work life, Winter's promising but flawed debut also tries to examine fertility, female friendships and mental health, as well as the Big Apple's art scene.

If you like this, read: Then We Came To The End by Joshua Ferris (Penguin, 2008, $19.36, Books Kinokuniya), another astute novel about the workplace.

Ho Ai Li

Join ST's Telegram channel and get the latest breaking news delivered to you.

A version of this article appeared in the print edition of The Sunday Times on September 04, 2016, with the headline Doorway to a past. Subscribe