NEW YORK • What a shock to wake up one morning and find armed men, who speak no language you know and look like no people you have ever seen, roaming the streets of your city.

And more shocking still to learn that your protectors - your leaders and army - had fled in the night. This scene repeated itself many times in China, beginning in the third century, when the Han dynasty collapsed and non-Chinese nomads swept down from the north and breached the Great Wall.

They brought fear with them, but other things too: knowledge, beliefs and cultural curiosity, which turned into respect or something like it. That respect worked two ways. Gradually, the invaders came to look, sound and be Chinese. And the Chinese began to have an expanded, sharper sense of themselves.

Exchange is the dynamic that animates Art In A Time Of Chaos: Masterworks From Six Dynasties China, 3rd-6th Centuries, the inaugural exhibition at the China Institute Gallery's new home in Lower Manhattan. The show is a jewel.

Season after season, the institute brings extraordinary treasures to New York, many directly from China, loans that even big-budget museums might have trouble nailing. With this material, it creates exhibitions that not only advance scholarship, but also give unalloyed pleasure, partly because the scale is always right.

After Han rule ended, China was effectively split in half, with the north ruled by foreigners and the south by the Chinese. Each half further splintered into successions of rival kingdoms fighting among themselves. The centrelessness lasted for almost four centuries.

The show views the period known as the Six Dynasties - or in China, as the Northern and Southern Dynasties - through some of its distinctive cultural achievements, which included refinements in celadon porcelain, growth of Buddhism and advances in calligraphy and painting. And it draws its illustrative material from three of China's major regional art institutions: the Shanxi Museum in the north and, in the south, the Nanjing Museum and the Nanjing Municipal Museum.

Calligraphy in China found its most famous exemplar, Wang Xizhi (AD303-361), in the Six Dynasties period. In the fourth century, he and his family were among the many upper-class northerners who relocated south to Nanjing. There, he devoted himself to Buddhist and Taoist studies which, in his case, entailed some serious partying. And one party made him immortal.

One bright day in AD353, he and 41 of his scholarly friends gathered at a picnic spot, the Orchid Pavilion, to drink wine and compose poetry. The plan was to collect the poems in an album and, at some point in the hard-drinking day, Wang wrote an account of the feelings the gathering inspired in him.

The result was a kind of lyric lamentation on the transient beauties of emotion, friendship and nature and a call to turn attention towards those things and away from the demands of professional ambition and civic life.

The message sounded a note of political resistance in a Chinese culture shaped by Confucian ethics. Wang's validation of individualism and vulnerability - implied by the polygraphic movement of the brush in his hand - had deep resonance in an insecure time.

The resonance lasted. Preface To The Poems Composed At The Orchid Pavilion became the most widely emulated work of calligraphy in Chinese history, the model for a new standard of expressive writing.

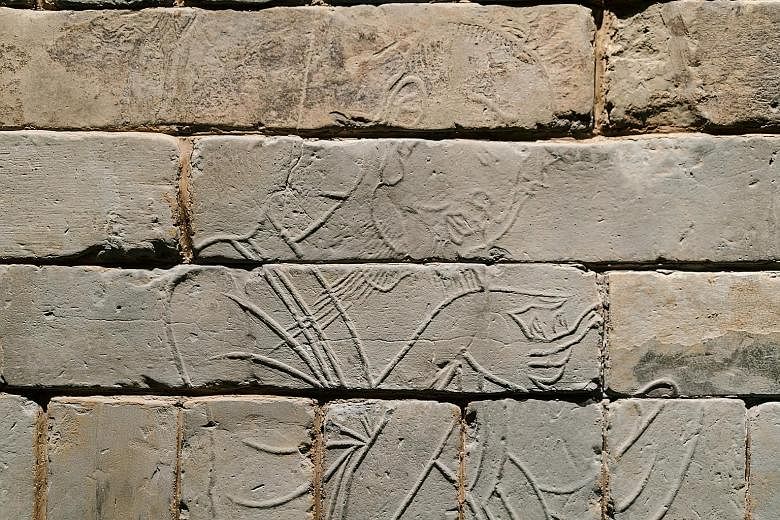

Although Wang's original manuscript was lost long ago, the touch of his brush was preserved and replicated countless times in copies traced on silk or paper, or carved into stone tablets. Any link to his spirit, at whatever degree of separation, is valued and the show has one in a different calligraphic text: the carved stone epitaph of the great calligrapher's young cousin Wang Xingzhi (AD310-340), unearthed in 1965 in the family burial ground near Nanjing.

The expressive connection between calligraphy and painting was always close, although Six Dynasties painting, like writing, survives mostly in second-hand form.

NYTIMES