Drifting 2,000m below the ocean in complete darkness is a yellow, grapefruit-sized creature that has been dubbed the Dumbo octopus for its wing-like fins which flap gracefully as it moves.

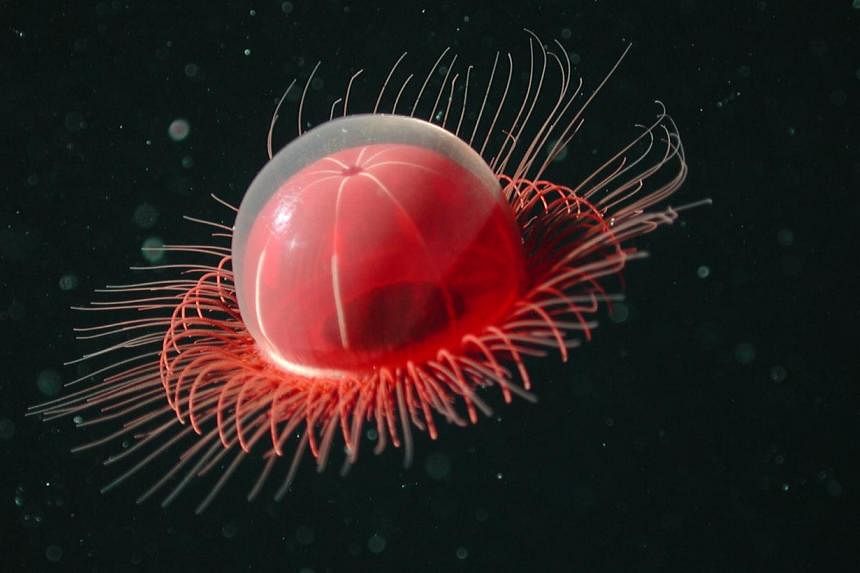

Then there is the Tiburonia granrojo, The Big Red, a velvety-looking dark red jellyfish that does not have any stinging tentacles, but catches prey with its long, fleshy arms.

These are just two of the many unstudied, mysterious deep sea creatures that have had little contact with man.

Now, you can see preserved specimens of some of these creatures at The Deep, a new exhibition which opens at the ArtScience Museum today.

Curator Claire Nouvian says of the animals: "I think they look spectacular and they've been very understudied. Very little is known about them, so it's just like exploring the deep forest in the 19th century, or Antarctica at the beginning of this century - it feels like a new frontier."

For instance, when The Big Red was discovered in 2003 off the coast of California, it was so unlike any other jellyfish that biologists had to create a new genus for it.

At the exhibition, there are also 18 luminescent glass sculptures of deep sea creatures by Australian artist Lynette Wallworth and 67 pictures of these underwater aliens.

But the highlight is undoubtedly the more than 40 preserved specimens of rarely seen deep sea animals, most of which were captured at between 2,000m and 4,000m underwater.

Ms Nouvian - the founder and director of Bloom Association, a non-profit organisation with branches in Paris and Hong Kong which was set up to protect the oceans - collected a large number of these specimens herself.

She descended to the depths in a manned submersible. Then, she either caught the creatures with scientific nets or sample boxes attached to the arms of the pod.

It is an arduous and potentially dangerous process to gather these creatures.

The submersibles have to be built to withstand immense pressure - at 2,000m, the craft is subject to about 200 times the normal atmospheric pressure - and they often travel slowly, descending 1,000m in half an hour.

After capturing the animals, keeping them alive is impossible and many of them die before reaching the surface.

Ms Nouvian says: "They may not die instantly, but the difference in pressure is really quite radical and their physiology cannot take the difference. There are also differences in the temperature and salinity of the water."

She adds that an overwhelming number of deep sea creatures are gelatinous, without a firm body, such as jellyfish and siphonophores, which are colonies of many small organisms grouped together.

Their gelatinous state is an adaptation to the scarcity of food and nutrients at the bottom of the ocean.

Ms Nouvian notes: "Being gelatinous is a good growth strategy because it doesn't cost much in terms of input - you can grow gelatinous tissues very easily, with very little to eat. It's basically just water, held together with a little bit of collagen."

However, because of their lack of firmness, such jelly-like creatures are difficult to preserve and exhibit.

"We tried really hard, for example, there were some jellyfish that looked so spectacular I really wanted to show them, but they just don't stay together and don't stay put, so we had to let go of that option."

The animals on exhibit have firm bodies, such as the bioluminescent black dragonfish and the long-nosed chimaera, which has a curved, pointed snout. They are fixed in a mixture of formaldehyde and water and held in place with thin, transparent threads.

Ms Nouvian says she hopes that visitors will be as enthralled by these animals as she is. "The deep sea is a new realm for knowledge and understanding, which I find fascinating.

"These are the ecosystems at the heart of our planet in terms of recycling nutrients and stabilising climate, but very little has been studied so far."