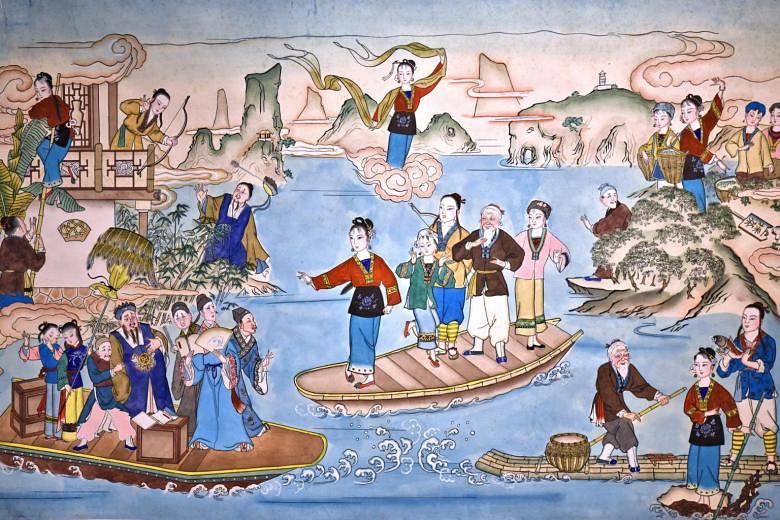

TIANJIN, CHINA - An elegant Chinese concubine stands alone in a lakeside pavilion that is flanked by rolling green hills. With a pained expression, she stares at a lotus leaf floating on the water.

The young woman, Yang Guifei, came to this romantic location to meet her powerful lover, Tang Dynasty Emperor Xuanzong.

When he fails to arrive, having chosen to spend time with other concubines, the crestfallen beauty tries to drink away her sorrows. But she becomes belligerent and, within earshot of others, makes disrespectful comments about the emperor which could endanger their relationship.

A real-life figure, Yang was so attractive, she reputedly distracted Xuanzong to the extent he was caught off-guard by the AD755 An Lushan Rebellion against the Tang Dynasty.

The tale of her drunken sorrow is told through one image. Titled Intoxicated Yang Guifei, this is an ancient print so beautiful and serene that it belies the gloomy story it tells.

I had admired its delicate depictions for several minutes before reading the English explanation alongside it in Tianjin's Yangliuqing Wood New Year Picture Museum. The image that entranced me is a Nianhua, or Chinese woodblock New Year Print.

It began as holiday decorations before evolving over centuries into one of China's most revered art forms. Now, Nianhua are like time capsules that highlight the customs, myths and politics of bygone eras in the country.

Woodblock prints in China can be traced back more than 1,500 years. They involved artists carving intricate patterns or scenes into pieces of wood, which were then pressed onto paper, creating ink outlines to be coloured in by hand. Most of these early Chinese woodblock prints focused on religion.

When the Nianhua style of woodblock prints began to boom in the latter part of the Ming Dynasty (1368 to 1644), it altered this artistic landscape. Nianhua aimed to tell more complex tales and addressed a far wider range of themes - from love to betrayal, murder to corruption and seduction to war.

It was, in this sense, a more populist artform than earlier Chinese woodblock prints. Nianhua was designed to appeal to a mass audience, particularly in rural China, where literacy rates were low, making these prints an effective mode of communicating philosophy, folk tales and even current affairs.

In the 1600s, their popularity exploded. First hundreds, then thousands, then millions of Nianhua were sold all over China. They were hung on doors or interior walls of homes, particularly during Chinese New Year.

Nianhua were not just attractive decorations, however. They were also believed to protect a household from negative forces and attract positive energy.

That was because many Nianhua featured symbols that were considered favourable in Chinese culture. Fish signified wealth, tigers stood for courage, plum blossoms represented persistence, peonies symbolised prosperity, lotus flowers embodied peace and dragons conveyed power.

These motifs were common across the three main styles of Nianhua, which became popular in the 1600s. In the pretty, canal-lined city of Suzhou, artists produced the Taohuawu style, known for its bold colours and patterns.

Shandong Province, meanwhile, became renowned for its Yangjiabu method, which often depicted scenes of everyday life.

Neither of those two styles, however, was as influential as Yangliuqing. Using a more graceful and understated aesthetic, which more closely resembled traditional Chinese paintings, Yangliuqing prints highlighted the majesty of Chinese landscape, architecture and fashion.

Originating from a village of the same name, in the eastern outskirts of Tianjin, Yangliuqing is the oldest and most revered form of Nianhua, having survived centuries of war, invasions and turmoil.

As I learnt during my visit to the museum, Yangliuqing almost died out after Japan invaded China in 1937. The Japanese stole or destroyed many of Tianjin's engraved wood blocks.

By this point, Nianhua had also become a somewhat outdated method of creating artworks. That was due to the spread across China of lithography, a style of printing that offered greater clarity and speed of production.

According to this museum, Nianhua survived only due to the intervention of the Chinese government. After World War II, it gathered many of the surviving woodblocks and offered financial support to Nianhua artists.

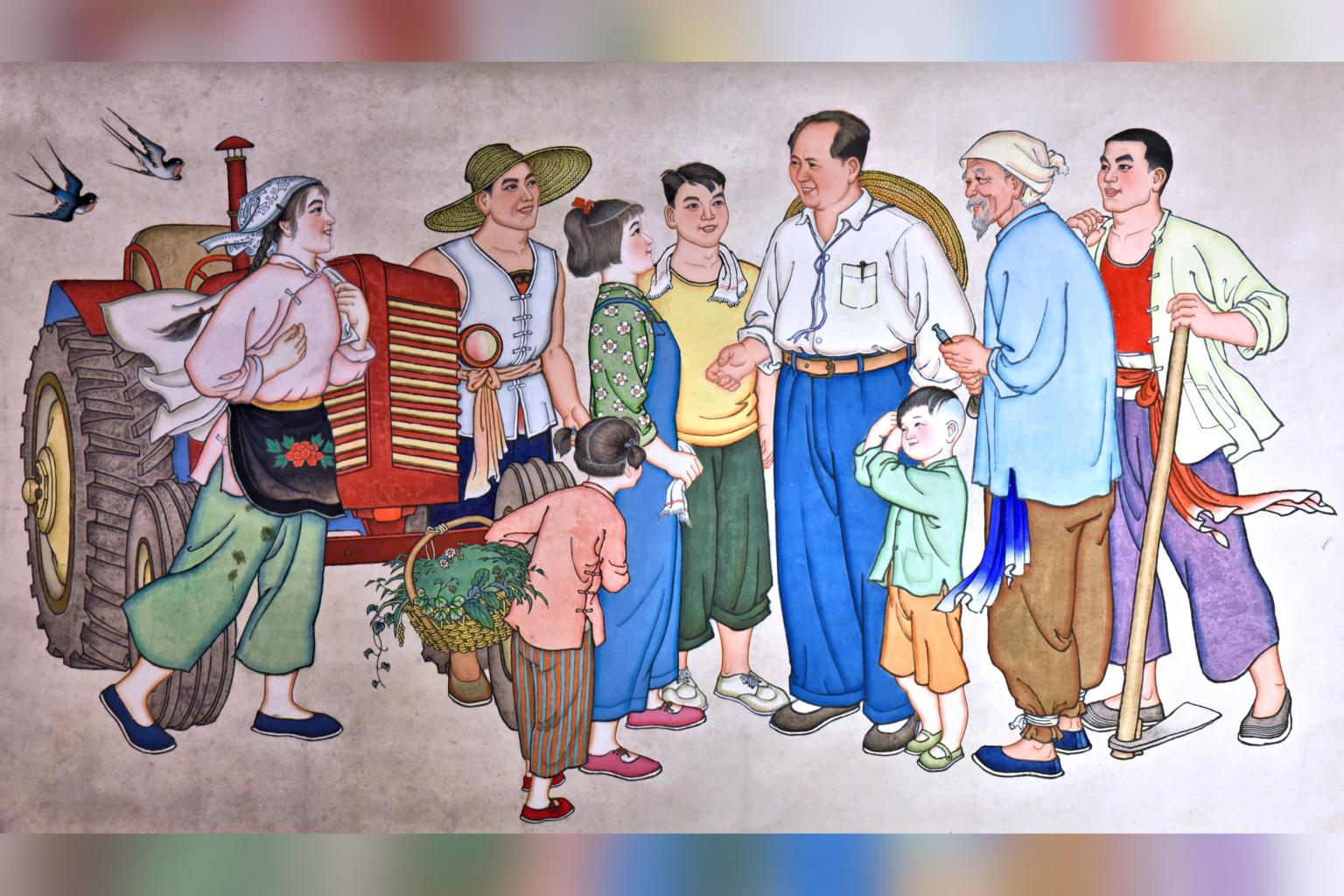

It has been widely documented that Nianhua then came under threat again due to Mao Zedong's Cultural Revolution (1966 to 1976).

During this tumultuous era, Mao attempted to suppress dissent. Artists were viewed as political provocateurs who sought to destabilise the nation. Mao's government outlawed traditional artforms like Nianhua to flood its population with sophisticated visual propaganda instead.

These government posters and paintings were starkly different in appearance to Nianhua. This was clear to me when I visited Shanghai's Propaganda Poster Art Museum on my last visit to the city.

While Nianhua featured gentle colours, majestic motifs and willowy, attractive human figures, Mao's propaganda used bold palettes, forceful slogans and dynamic representations of Chinese people at work and war.

Once again, though, Nianhua persisted. As the memories of Mao's chaotic reign faded, New Year prints returned to the mainstream.

To this day, many Chinese people still display Nianhua. In cities across China this month, when Chinese New Year will be celebrated, Nianhua will embellish countless homes, shops and offices.

Many of these artworks will feature door gods, also known as menshen. These fearsome Taoist deities are viewed as guardians that shield humans from evil or misfortune and guide them into a prosperous new year.

More than a millennium after woodblock printing first emerged in China, this ancient practice remains relevant, thanks to Nianhua.

• The writer is an Australian journalist and photographer based in Perth.