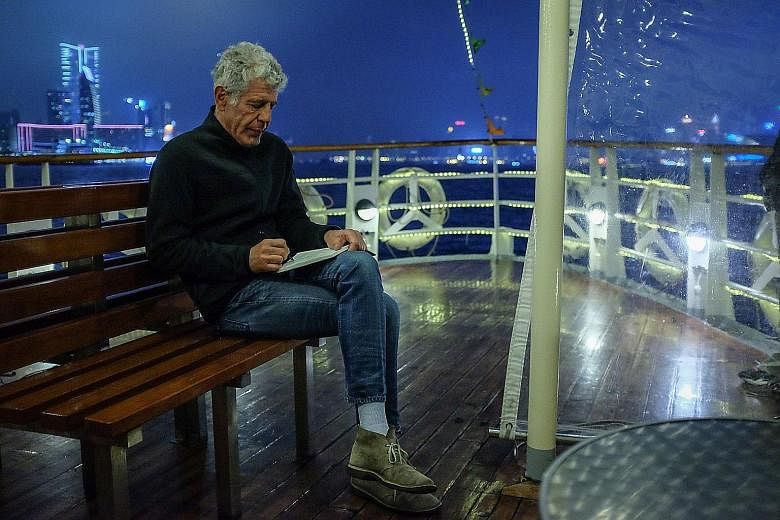

NEW YORK • The new Anthony Bourdain documentary, Roadrunner, is one of many projects dedicated to the larger-than-life chef, writer and television personality.

But it has drawn outsize atten-tion, in part because of its subtle reliance on artificial intelligence technology. Using several hours of Bourdain's voice recordings, a software firm created 45 seconds of new audio for the film.

The AI voice sounds just like Bourdain speaking from the great beyond; at one point, it also reads an e-mail he sent before his death by suicide in 2018.

"If you watch the film, other than that line you mentioned, you probably don't know what the other lines are that were spoken by the AI and you're not going to know," Morgan Neville, the director, said in an interview with The New Yorker. "We can have a documentary-ethics panel about it later."

The time for that panel may be now. The dead are being digitally resurrected with growing frequen-cy: as 2D projections, 3D holograms, CGI renderings and AI chat bots.

A holograph of rapper Tupac Shakur took the stage at Coachella in 2012, 15 years after his death; a likeness of a 19-year-old Audrey Hepburn starred in a 2014 Galaxy chocolate ad; and Carrie Fisher and Peter Cushing posthumously reprised their roles in some of the newer Star Wars films.

Few examples drew as much attention as the singing, dancing hologram that Kanye West gave Kim Kardashian West for her birthday last October, cast in the image of her late father, Robert Kardashian. The hologram's voice was trained on real recordings but spoke in sentences never uttered by Kardashian.

Mr Daniel Reynolds, whose company, Kaleida, produced the hologram of Kardashian, said costs for such projects start at US$30,000 (S$40,831) and can run higher than US$100,000 when transportation and display are factored in.

But there are other, much more affordable forms of digital reincarnation. On the genealogy site MyHeritage, visitors can animate family photos of relatives long dead, essentially creating innocuous but uncanny deepfakes, for free.

Though most digital reproductions have revolved around people in the public eye, there are implications for even the least famous. Just about everyone these days has an online identity, one that will live on long after death.

Determining what to do with those digital selves may be one of the great ethical and technological imperatives of our time.

We produce so much data that some philosophers now believe personhood is no longer an equation of body and mind; it must also take into account the digital being.

Mr Carl Ohman, a digital ethicist, said this represents a huge sociological shift; for centuries, only the rich and famous were thoroughly documented. In one study, he calculated that - assuming its continued existence - Facebook could have 4.9 billion deceased users by the century's end.

That figure presents challenges at both the personal and societal level, Mr Ohman said: "It's not just about,'What do I do with my deceased father's Facebook profile?' It's rather a matter of 'What do we do with the Facebook profiles of the past generation?'"

Public social media profiles are one thing. Private exchanges, such as the e-mail read in the Bourdain documentary, raise more complicated ethical questions.

"We don't know that Bourdain would have consented to reading these e-mails on camera," said Associate Professor Katie Shilton, a researcher focused on information technology ethics at the University of Maryland.

"We don't know that he would have consented to having his voice manipulated." She described the decision to have the text read aloud as "a violation of autonomy".

In an interview with GQ, director Neville said he "checked" with Bourdain's "widow and his literary executor", who approved of his use of AI.

For her part, Bourdain's ex-wife Ottavia Busia said she did not sign off on the decision. "I certainly was NOT the one who said Tony would have been cool with that," she wrote on Twitter on July 16, the day the film was released in theatres.

In the case of public figures, there is an obvious financial incentive to create their digital likenesses, which is why their images are protected by posthumous publicity rights for a certain period of time. In California, it is up to 70 years after death; in New York, as of December last year, it is 40 years post-mortem.

If a company wants to use the image of a deceased person sooner, it requires consent from the deceased's estate; resulting collaborations can be mutually profitable. As such, moral guardianship can be complicated by financial motives.

Some artists are explicitly expressing their desires. Robin Williams, for instance, who died in 2014, filed a deed preventing the use of his image, or any likeness of him, for 25 years after his death as an extra layer of protection on top of California's law.

Consumers are also making their opinions known. The company Base Hologram, which has produced hologram shows of Roy Orbison, Buddy Holly and Maria Callas, reversed plans to put likenesses of both Whitney Houston and Amy Winehouse on tour after they were criticised as exploitative.

Just because producing such performances is legal does not mean audiences will accept them as ethical.

NYTIMES