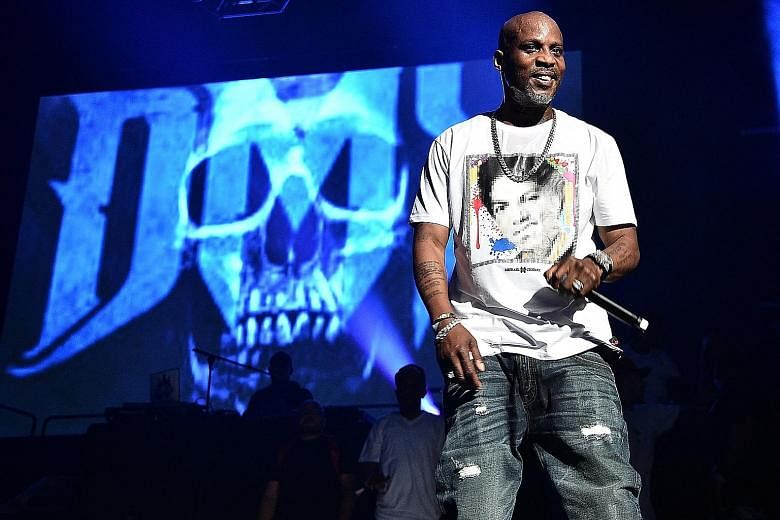

Even when DMX was the most popular rapper on the planet, he was a genre of one: a gruff, motivational, agitated and poignant fire-starter - pure vigour and pure heart; a drill sergeant and a healer.

In 1998 and 1999, he released three majestic, bombastic albums: It's Dark And Hell Is Hot, Flesh Of My Flesh, Blood Of My Blood and ... And Then There Was X.

Each one debuted at No. 1 on the Billboard album chart and has been certified platinum several times over.

He performed at Woodstock in 1999 for hundreds of thousands of people. He starred in Belly, the seminal 1998 hip-hop noir film. In his songs, he growled like a dog, credibly and often.

And yet there were no DMX clones in his wake because there was no way to falsify the life that forged him.

For DMX - who was born Earl Simmons and died last Friday at 50 after suffering a heart attack on April 2 - hip-hop superstardom came on the heels of a devastating childhood marked by abuse, drug use, crime and other traumas.

His successes felt more like catharsis than triumphalism. Even at his rowdiest and most celebrated, he was a vessel for profound pain.

Especially as he got older, and his public struggles - countless arrests, stints in jail, continuing problems with drugs - threatened to overshadow his musical legacy, he never hid his hurt nor let shame overshadow his truth.

The potency of his humanity was as heroic as any of his songs.

From the release of his debut Def Jam single, Get At Me Dog, in 1998, DMX was an immediate titanic presence in hip-hop.

Just as the genre was moving towards polished sheen, he preferred iron and concrete - rapping with a muscular throatiness that conveyed an excitable kind of mayhem.

Often, he rapped as if he were trying to win an argument, with repetitive emphasis and terse phrasing designed for maximum impact. Even when he dipped into flirtation, like on What These B***hes Want, he did not change his approach.

Even though his time at the top of the genre was relatively brief - just a few ferocious years - he was never erased from its collective memory.

That is partly because the tumult of his personal life constantly landed him in the spotlight.

He was arrested dozens of times for charges including drug possession, aggravated assault, driving without a licence and tax evasion.

He rescued stray dogs and tattooed a tribute to one of them, Boomer, across the whole of his back, but he also pleaded guilty to animal cruelty charges.

Yet DMX remained a subject of sympathy: he was a wild man and a broken one too. Physically abused by his mother as a child, he spent significant stretches of time in group homes. He took to crime at a young age, specialising in robbery.

Many of the stories contained in his 2002 book, E.A.R.L.: The Autobiography Of DMX, are matter of fact and harrowing. His life became a tug of war between his musical gift and traumas. And in the mid-2000s, he began to fade from the charts.

His turns on the big screen, in Belly, Romeo Must Die (2000) and Exit Wounds (2001), gave way to appearances on sometimes voyeuristic reality television programmes like Couples Therapy (2012 to 2015), Dr Drew's Lifechangers (2011 to 2012) and Iyanla: Fix My Life (2012 to present).

His search for healing - his need for it - became central to his public narrative.

NYTIMES