Despite periodic bad publicity when thousands of mom-and-pop investors lost big money on equity-linked notes such as those tied to the Lehman Brothers collapse and the China Aviation Oil debacle, structured notes have made a strong comeback as the memory of each crisis fades from public consciousness.

It is not a recent phenomenon.

Two years ago, a Sunday Times report mentioned that structured products were back with a bang as investors sought higher returns amid the paltry interest rates they got for their savings.

This remains the case today as low interest rates prevail amid an anaemic global economic environment. Unlike in the past when these instruments were sold to all and sundry, financial institutions are more careful in selling structured products these days.

Disclosure standards have improved, with various risks, scenarios and warnings flagged prominently in presentation materials used to market the products.

Nonetheless, these are but cosmetic changes that do not address a key issue: Most structured products do not compensate investors enough for the risks they are assuming.

To help illustrate this, I shall highlight an actual product that a friend bought last June.

The name of the product was a mouthful: Six-month, Singapore-dollar non-principal guaranteed autocallable fixed coupon note with memory autocall linked to three shares.

It carried a fixed coupon of 8.01 per cent a year, payable monthly provided that "events" that would trigger an early redemption had not occurred.

The events were tied to the performance of three United States-based technology stocks: Google, Intel and Oracle.

The minimum investment was $100,000 for an accredited or sophisticated investor as defined in the Securities and Futures Act. For other investors, the minimum subscription was $200,000.

As the name suggested, this product - let's call it Memory Autocall for short - was fairly complicated.

I asked my friend if she fully appreciated or understood what she had bought with her $200,000 investment. Her answer was no.

But she admitted to being given a chance to change her mind when she got a follow-up call from the bank's customer relations officer a few days after signing on the dotted line. Under rules to safeguard consumer interests, investors are given a seven-day cooling-off period when investing in structured notes.

During this period, they can back out with their capital intact and without incurring sales charges or commissions. She said her mistake was to go ahead, despite a distant warning bell sounding in her head as a result of the call.

She had also received ample warnings, including a written statement on the cover sheet that stated in capital letters the product was a complex investment and one should not buy it without fully understanding it.

Here is how Memory Autocall worked: The investor would receive a coupon payout of 0.6675 per cent of the principal amount each month, for six months.

But should the three stocks close at or above their initial prices on certain set valuation dates, a knockout event is deemed to have occurred. This would lead to the termination of the note, as a result of which the investor would get back her principal plus the coupon for that month.

She would also get to keep the coupons paid out earlier.

The three stocks did not need to meet the initial price threshold at the same time for the knockout event to take place.

If this does not sound complicated enough, there was another scenario known as the knock-in event to consider.

This would occur should any of the stocks fall to 80.5 per cent or lower of their initial price on any given valuation dates.

On the final valuation date, should the closing price of the worst-performing stock stay below its initial price, the investor's principal would be used to purchase the stock at the initial price. Under this scenario, a loss of capital is guaranteed.

This was exactly what happened to my friend's investment.

During the note's lifespan, Google shares soared.

On the other hand, Intel and Oracle wobbled from the start and kept falling. Both came perilously close to hitting their knock-in prices of US$25.2126 and US$35.6937 respectively on Aug 26, the second valuation date from the note's inception.

It was a lucky escape as Intel and Oracle had closed at US$25.87 and US$35.45 respectively the day before. But her luck ran out on the next valuation date on Sept 28, when Oracle closed at US$35.44.

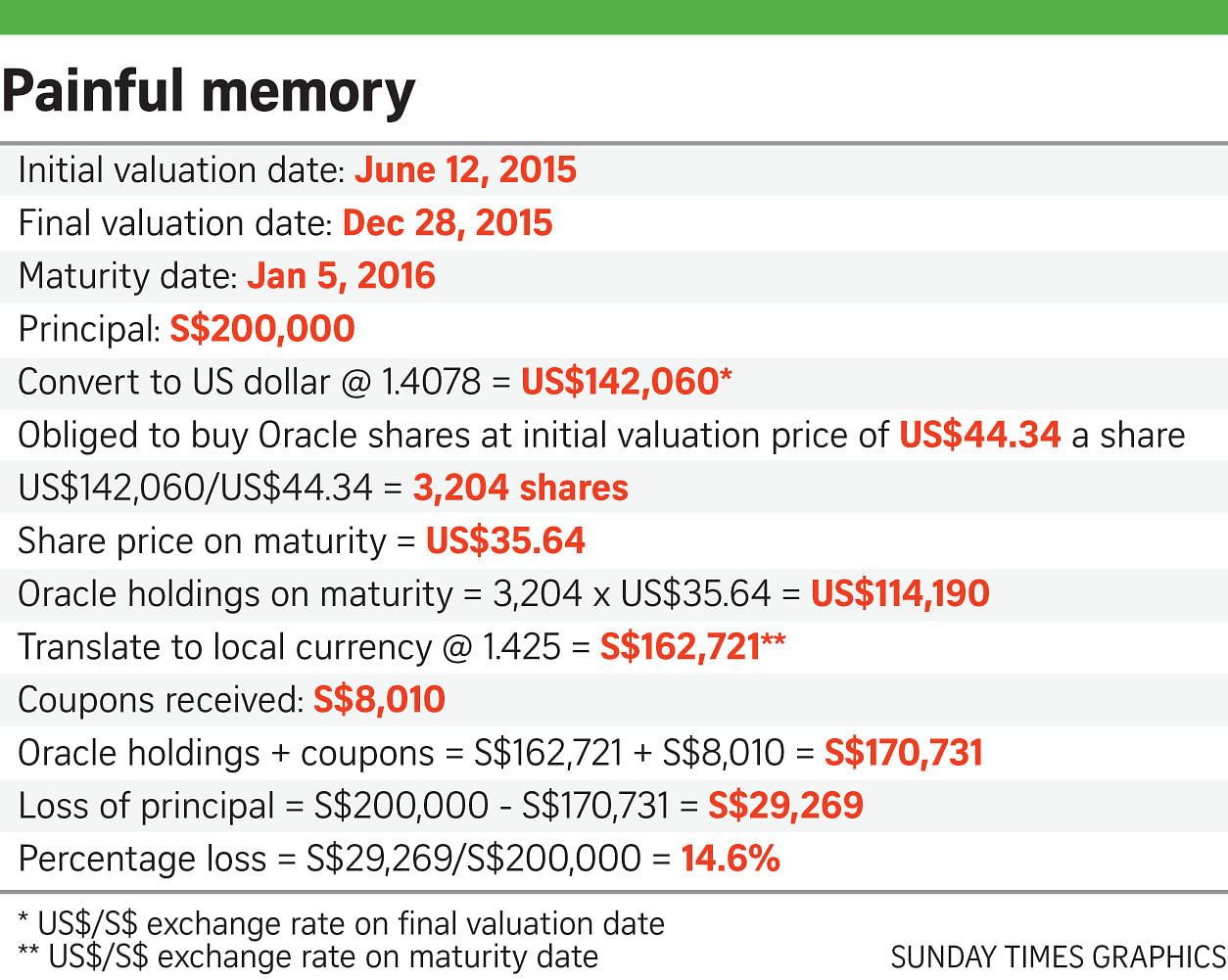

From then on, the investment was doomed even as my friend continued to receive her monthly coupons, given there was little chance that Oracle could recover to the initial price in the remaining three months. On maturity, a back-of-the-envelope calculation showed that my friend had suffered a loss of about $29,000 even after factoring in the $8,010 in coupon payments she collected.

On top of that, she was left holding Oracle shares bought at a high price - an outcome that she had not bargained for. She is still debating whether to sell the shares or hold on for a better price.

It bears repeating what I said earlier: Structured products do not compensate investors enough for the risks they are assuming.

My friend lost almost 15 per cent of her capital chasing an investment that would have, under ideal conditions, earned her 4.005 per cent at best.

How ideal must these conditions be? Well, the stocks had to stay within a predefined band - below their initial price but higher than 80.5 per cent of that price - on each of the six valuation dates between June and December last year.

This is easily achievable if these were consumer staple companies, whose share prices tend to be relatively stable. However, the three reference stocks under Memory Autocall belong to the highly volatile tech sector, in which price swings of 20 per cent or more within six months among its constituents are not remarkable.

This is underscored by the fact that the share prices of Oracle, Intel and Google transversed as much as 27 per cent, 36 per cent and 48 per cent respectively from their lows to their highs between the initial valuation date on June 12 and final valuation date on Dec 28.

To be sure, just because the investment yielded a poor outcome is not why I believe Memory Autocall is inappropriate for most retail investors. Its sheer complexity makes it an inappropriate choice for them.

Memory Autocall had the hallmarks of a protective put, a sophisticated risk-management strategy that investors use to protect themselves against unrealised losses on a stock they already own.

A protective put is a kind of insurance policy on a stock investment. For a small premium, the buyer of the option has the right to sell an underlying asset at a predetermined price within a stipulated period to the seller or underwriter of the put.

Does not this undertaking by the seller of the put bear a close resemblance to what Memory Autocall investors were obliged to do? Few of them would realise that they were effectively asked to play insurer and take on the risky bets of other investors.

Professional option sellers understand these risks and have measures to ameliorate them, but ordinary retail investors do not.

They are also less likely to be able to tell if the premium of 8.01 per cent a year is sufficient compensation for underwriting the downside risk on not one or two but three stocks in a single instrument.

This is also complicated by the fact that Memory Autocall was not an ordinary put option, as reflected by the various restrictions before it could be exercised.

A 15 per cent loss in six months can be considered rather steep. No professional outfit can afford to leave themselves so exposed without going out of business in a jiffy. For retail investors, such losses, although no less painful, tend to be non-recurring as those affected lick their wounds and swear off similar investments in future. But memories fade.

Retail investors are also ubiquitous and plentiful.

So I am afraid my friend's bitter experience will be repeated by others, again and again.

Few Memory Autocall investors would realise that they were effectively asked to play insurer and take on the risky bets of other investors.