This story, published on June 19, 2015, was updated on July 1, 2015.

Back in 2009 when the Greek crisis first hit the headlines, there were dire warnings of how a debt default by Greece could lead to the collapse of the eurozone and other grim consequences for global banking and the world economy.

Five years on, Greece is back in the headlines and really running out of time and money. On July 1, Greece became the first developed country ever to fall into default with the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

The default could push the Greek government towards leaving the single currency, a prospect that has become known as Grexit.

But while some things about the Greek crisis remain the same from 2009, others have changed.

Just how important is Greece today to the world economy - and would a default still have the potential to upend the global economy?

Here are 5 things to consider:

1. Greece's economy has shrunk

For Greece, a forced default and exit from the euro could spell great economic misery for the country, at least in the short term. A return to the drachma, instant devaluation, rampant inflation and a likely banking crisis. It could end up a pariah in the international markets for years like Argentina in 2002.

But the Greek economy has shrunk by 25 per cent since 2010 so it now makes up just 2 per cent of the eurozone economy.

Also, the broader European economy has some buffers in place to support it: A weaker euro, down 20 per cent from where it traded a year ago, is helping to boost exports and a €1 trillion (S$1.52 billion) monetary stimulus programme from the European Central Bank (ECB) has boosted lending.

2. Not a huge shock to markets

The fact that a default in Greece has been anticipated for some time means that the actual event is unlikely to be a huge surprise to global markets, or have a destabilising impact to the degree that the collapse of US investment bank Lehman Brothers did in 2008.

Perhaps the most notable sign of investors are not that fazed over whether Greece defaults or not is the the fact that the euro - the asset which would be most directly affected by Grexit - has risen while the crisis intensified.

3. Financial contagion risks have been cut

Contagion is the bogeyman of the ongoing Greek drama. The financial contagion risks, analysts told CNBC, should not be underestimated, but are lower than at previous flashpoints in the Greek crisis.

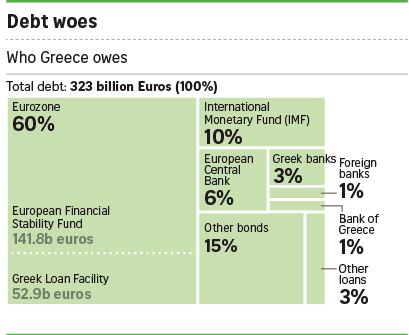

There are two reasons for this, the first being that the big holders of Greece's massive debt is now the IMF, the European Central Bank (ECB) and eurozone government rather than private lenders. This should help limit any ripple effects from a default.

"We know who the big owners of Greek government bonds are - the IMF and ECB - and we know they have deep pockets," Mr Julian Jessop, chief global economist at Capital Economics told CNBC. "We wouldn't worry about the solvency of the IMF or ECB if Greece defaults."

The second reason why contagion risks from Greece are viewed differently from a few years ago is that the European Union has worked hard to cordon off the banking difficulties of one member state from the other 27.

4. But geopolitical risks remain strong

Given its membership of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (Nato) military alliance and its location near to the Middle East and not far from Russia, Greece is a surprisingly important country in geopolitical terms, said CNBC. Thus a default that raises questions about its future in the euro zone is something to watch.

5. And what if other countries follow suit?

Several governments, particularly in Ireland, Portugal and Spain, are watching developments in Greece nervously on worries that a Greek default or Grexit will strengthen anti-austerity and anti-euro parties and movements in their own countries.

"It's more a Greek exit from the euro and others following that's a worry," Mr Jessop at Capital Economics told CNBC. "Then you're talking about the future of the world's second most important currency after the dollar."