For a whole generation of young investors, quantitative easing (QE) is the only central bank monetary policy they've ever known. The Federal Reserve's emergency measures, first announced in November 2008 on the eve of the global financial crisis, have endured for nearly nine years.

This era now appears to be coming to a close. The Fed will begin reducing its US$4.5 trillion (S$6.1 trillion) balance sheet this month, a significant step towards policy normalisation. To get there, it will cut reinvestment of the principal payments it receives on the securities it already owns. And it plans to do so at a predictable and measured pace: US$10 billion starting this month, rising every three months until it reaches US$50 billion.

Markets are rightly concerned, given the role QE has played in pushing investors into risk assets. The MSCI All Country World Index is up roughly 160 per cent from its 2009 lows, global high-yield spreads have fallen to multi-year lows, and real estate prices have surpassed their pre-crisis highs in much of Asia and key gateway cities globally. Past hints at reversing QE have been painful too, like the 2013 taper tantrum that sent US 10-year yields up some 50 basis points in just three weeks.

NOT AN END TO ECONOMIC CYCLE

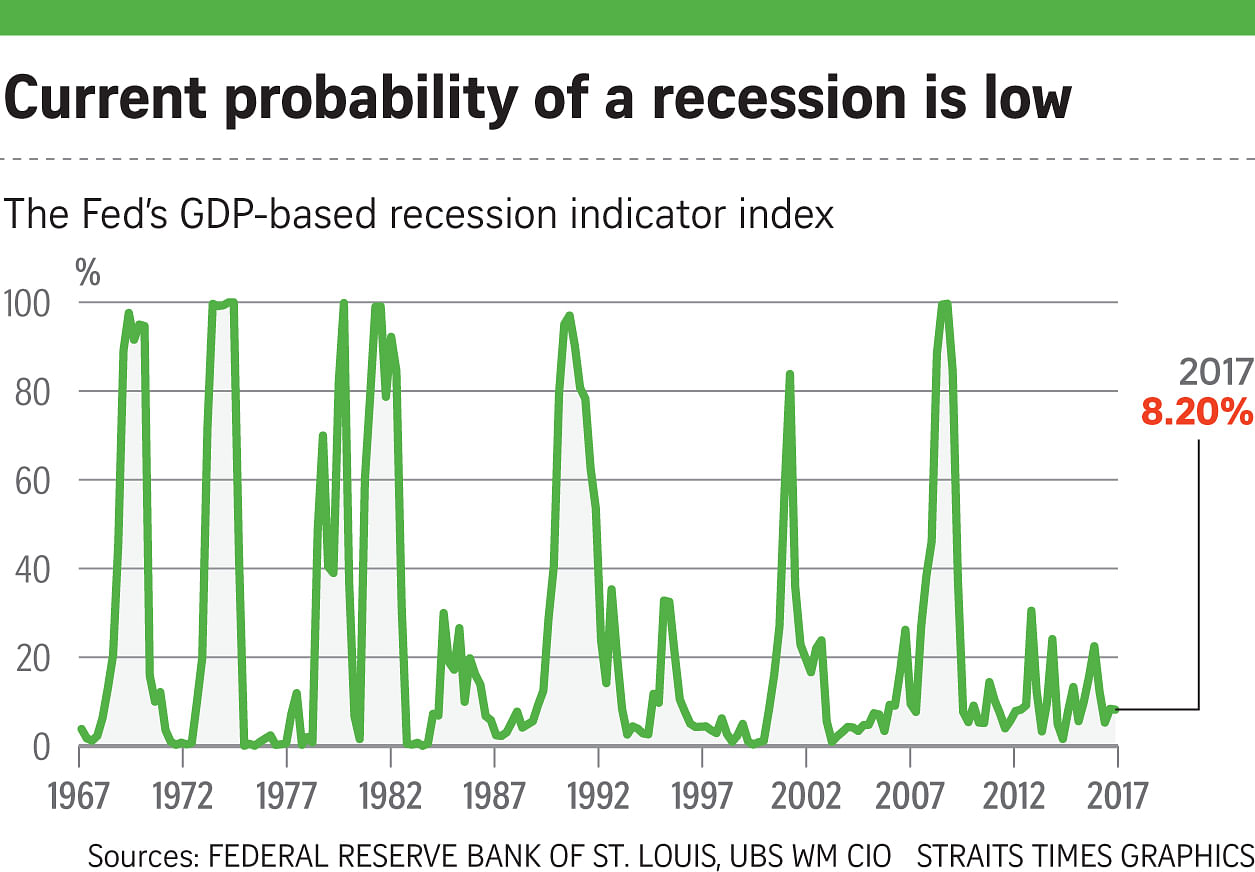

Arguably, volatility will go up and the risk of market disruption will increase as central banks become less active players in asset markets. But an end to QE does not imply an end to the economic cycle. The Fed's own gross domestic product (GDP)-based recession model points to a recession probability of just 8.2 per cent in the coming 12 months. The process of interest-rate normalisation is set to pass gradually over a number of years, with Fed Funds and 10-year Treasuries likely to hit a cycle peak at around 2.5 per cent and 3 per cent some time in 2019. This relatively gentle pace of rate rises should limit the chances of a major market correction, allowing the global economy to continue expanding at around trend.

Importantly, long-term rates will likely peak well below historic norms, backing our call to stay moderately "risk-on" and remain overweight in global equities. Nonetheless, we have booked some profits recently in the light of the 15 per cent rise in global equities so far this year, about twice our expected long-term returns on stocks.

NORMALISATION WON'T MOP UP GLOBAL LIQUIDITY

The Fed may be heading for the exit, but it won't be slamming the door. And they've hardly been alone at the stimulus party. Major central bank balance sheet growth peaked in 2009, with a cumulative annualised expansion rate of more than US$3 trillion. But since then, there have been another three major waves of stimulus from the world's major central banks (in 2012, 2014 and 2016), all of which weren't far from the US$2.5 trillion mark. The last of these waves continues to roll on, holding steady near US$2 trillion as of July, underscoring just how supportive central banks remain.

The Bank of Japan (BOJ) is perhaps most firmly in accommodative mode, as it grapples with still-subdued inflation even as growth rebounds. The central bank extended its bond asset-buying programme on Sept 21 and held short-term interest rates steady at minus 0.1 per cent. We expect the BOJ to maintain its current policy for some time into Fed normalisation, which could see the yen staying weak, with the US dollar-yen trading at or above 113.

GROWTH, EARNINGS AS DRIVERS

China still holds the key. Fed normalisation comes at a time China is already taking tentative steps towards tightening credit expansion. Better-than-expected corporate earnings - with industrial profits up 24 per cent on the year in August, and robust first-half GDP growth - should help China weather a much-needed push to deleverage the economy in the second half.

Likewise, the rest of Asia should be relatively shielded from a QE exit by a solid recovery in trade and profits, and mostly negligible inflation. Capex recovery remains at an early stage, and pro-growth policies are widely in place. Banks in seven out of 10 markets are seeing improved asset quality, so stronger lending should facilitate firmer corporate growth. The strategic case for equities is intact, with low double-digit earnings growth ahead for the second half of 2017 and next year. For markets like Singapore, where the economy is finally finding its feet, any spike in volatility on US rate normalisation should be taken as a healthy reset, rather than a more ominous sign.

Capital inflows to emerging market equities have increased sharply this year, rising by roughly US$50 billion. This trend could be tested by the Fed's QE exit, but we would expect any setback to be temporary. From a valuation angle, even as Chinese growth slows in the second half, its forward P/E ratios remain undemanding on a global basis at 14.5x, versus the US (19.1x), Japan (17.5x) and Europe (15.1x).

There are risks to the bull market from the withdrawal of excessive monetary support. Still, our probability assessment of a serious correction with knock-on real impacts is less than 10 per cent in the next 12 months. Rising GDP growth and robust global earnings are at last providing the necessary cover for central banks to unwind crisis-era super-low interest rates.

• The writer is the Asia-Pacific regional head at the chief investment office of UBS Wealth Management.