MEDAMAHANUWARA (Sri Lanka) • Past the end of a remote mountain road, in a concrete house that lacked running water but bristled with smartphones, 13 members of an extended family were glued to Facebook. And they were furious.

A family member, a truck driver, had died after a beating. It was a traffic dispute that had turned violent, the Sri Lankan authorities said. But on Facebook, rumours swirled that his assailants were part of a Muslim plot to wipe out the country's Buddhist majority.

"We don't want to look at it because it's so painful," H.M. Lal, a cousin of the victim, said. "But in our hearts there is a desire for revenge that has built." The rumours, they believed, were true. Still, the family, which is Buddhist, did not join in when Sinhalese-language Facebook groups, goaded on by extremists with wide followings on the platform, planned attacks on Muslims, burning a man to death.

But they had shared and could recite the viral Facebook memes constructing an alternate reality of nefarious Muslim plots.

The New York Times reporters have traced riots and lynchings linked to misinformation and hate speech on Facebook, which pushes whatever content keeps users on the site longest - a potentially damaging practice in countries with weak institutions and histories of social instability. Time and again, communal hatreds overrun the newsfeed unchecked as local media is displaced by Facebook and governments find themselves with little leverage over the company. Some users, energised by hate speech and misinformation, plot real-world attacks.

A reconstruction of Sri Lanka's descent into violence in February and March found that Facebook's newsfeed played a central role in nearly every step from rumour to killing. Facebook, officials say, ignored repeated warnings of the potential for violence, resisting pressure to hire moderators or establish emergency points of contact.

Facebook declined to respond in detail to questions about its role in Sri Lanka's violence, but a spokesman said in an e-mail that "we remove such content as soon as we're made aware of it". She said the company was "building up teams that deal with reported content" and investing in "technology and local language expertise to help us swiftly remove hate content".

Five hours east of Medamahanuwara lies the real Ampara, a small town of concrete buildings. But the imagined Ampara, which exists in rumours and memes on Sinhalese-speaking Facebook, is the shadowy epicentre of a Muslim plot to sterilise and destroy Sri Lanka's Sinhalese majority.

As Tamil-speaking Muslims, the Atham-Lebbe brothers knew nothing of that version of Ampara when they opened a restaurant there. They had no way to anticipate that, on a warm evening in late February, the real and imagined Amparas would collide.

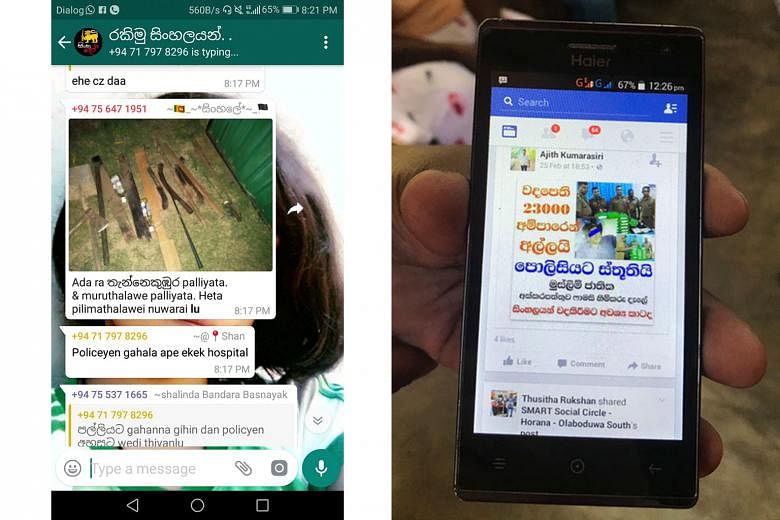

It began with a customer yelling in Sinhalese about something he had found in his dinner. Unable to understand Sinhalese, Farsith, the brother running the register, ignored him. He did not know that the day before, a viral Facebook rumour had claimed, falsely, that the police had seized 23,000 sterilisation pills from a Muslim pharmacist in Ampara.

The irate customer drew a crowd, which surrounded Farsith, shouting: "You put in sterilisation medicine, didn't you?" He grasped only that they were asking about a lump of flour in the customer's meal, and worried that saying the wrong thing might turn the crowd violent. "I don't know," Farsith said in broken Sinhalese. "Yes, we put?" The mob, hearing confirmation, beat him, destroyed the shop and set fire to the local mosque.

In an earlier time, this might have ended in Ampara. But Farsith's "admission" had been recorded on a cellphone. Within hours, a popular Facebook group, the Buddhist Information Centre, pushed out the 18-second video, presenting it as proof of long-rumoured Muslim plots. Then it spread.

In a small office in Sri Lanka's capital Colombo, members of an advocacy group called the Centre for Policy Alternatives watched as hate exploded on Facebook - all inspired by the video from Ampara.

Desperate, the researchers flagged the video and subsequent posts using Facebook's on-site reporting tool. Though they and government officials had repeatedly asked Facebook to establish direct lines, the company had insisted this tool would be sufficient, they said. But nearly every report got the same response: the content did not violate Facebook's standards.

As anger over the Ampara video spread online, extremists like Amith Weerasinghe, a Sinhalese nationalist with thousands of followers on Facebook, found opportunity. He posted repeatedly about the beating of the truck driver, M.G. Kumarasinghe, portraying it as further proof of the Muslim threat.

When Kumarasinghe died on March 3, online emotions surged into calls for action: attend the funeral to show support.

The researchers in Colombo reported Weerasinghe's video to Facebook, along with his earlier posts, but all remained online. Over the next three days, mobs descended on several towns, burning mosques, Muslim-owned shops and homes.

In response, the government temporarily blocked most social media. Only then did Facebook representatives get in touch with Sri Lankan officials, they say. Weerasinghe's page was closed the same day.

Last year, in rural Indonesia, rumours spread on Facebook and WhatsApp, a Facebook-owned messaging tool, that gangs were kidnapping local children and selling their organs. Some messages included photos of dismembered bodies or fake police fliers. Almost immediately, locals in nine villages lynched outsiders they suspected of coming for their children.

Near-identical social media rumours have also led to attacks in India and Mexico.

Government officials in Sri Lanka say Facebook wields enormous influence over their society, but they have little control over Facebook. Even blocking access did not work. One official estimated that nearly three million users in Sri Lanka continued accessing social media via Virtual Private Networks, which connect to the Internet from outside the country.

"We don't completely blame Facebook," said Harindra Dissanayake, a presidential adviser in Sri Lanka. "The germs are ours, but Facebook is the wind, you know?"

NYTIMES