BANGALORE - As India enters the second week of its 21-day lockdown to combat the spread of Covid-19, manufacturers and retailers are raising the spectre of an impending shortage of food and essential goods in the market.

The cause is a massive breakdown in the supply chains as all movement of people, goods and services has been suspended.

Many wholesale markets are empty of produce. If the produce does arrive from farms and factories, there are no trucks or drivers to take them to the shops and supermarkets.

The Indian government permits essential goods to be produced, transported and sold during the lockdown, but it took a few days for district authorities and the police to figure out what was essential and what was not.

Many states have issued curfew passes to transport essential items, but manufacturers say it has been impossible to get permission for the entire supply chain.

"I cannot sell the biscuits without packaging," said Mr Sreenivasulu Vudayagiri, chief executive of biscuit manufacturer Unibic, which closed its Bangalore factory on Sunday.

Biscuit and cheese maker Brittania's chief executive Varun Berry said the country would run out of packaged food in a week if supply chains were not fixed.

On March 30, the Indian government ordered that transport of both essential and non-essential goods be allowed, but production and supply are still severely hit owing to varied state practises.

"The local administration doesn't allow the movement of delivery vehicles and workers. There is also fear among workers and truck drivers to come to work because there were reports of police harassment," said Mr Arvind Mediratta, managing director of METRO Cash & Carry, a multinational wholesale chain.

States like Karnataka, Kerala, Telangana, Delhi, Maharashtra and West Bengal have issued curfew passes and created task forces headed by senior policemen to ensure smooth movement of goods.

But Mr Mediratta says Punjab, Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat and Rajasthan have totally closed their borders, shut down bulk supply yards and banned all transport.

"These closed states are the main hubs of spices, grains and pulses. We are beginning to see a major shortage of pulses in the market," he said.

The Retailers Association of India (RAI) said there are more than 1.5 million modern retail stores in India, generating business of almost 4.74 billion rupees and employing more than 6 million people.

In the past one and a half months, RAI said earnings had dropped to 15 per cent.

"If the lockdown continues till June, then we will be staring at 30 per cent of retail stores shutting down for good, leading to 1.8 million people losing their jobs," said Mr Kumar Rajagopalan, RAI's chief executive.

The Confederation of All India Traders estimate the retail sector has lost US$30 billion (S$43 billion) in 15 days.

The government allows online delivery of groceries, but apps like Grofers and BigBasket ran out of stocks on Day 1 of the lockdown.

The e-commerce market for groceries in India is only 2 per cent.

Most Indians buy from small neighbourhood grocers.

And in Bangalore, Chennai and Delhi, many have downed their shutters.

Mr Ganesh Rao, who manages a 15x15 feet general purpose store in south Bangalore, had only some toffees and a few bars of detergent left on his shelves. With no hope of getting new stocks, he was closing shop.

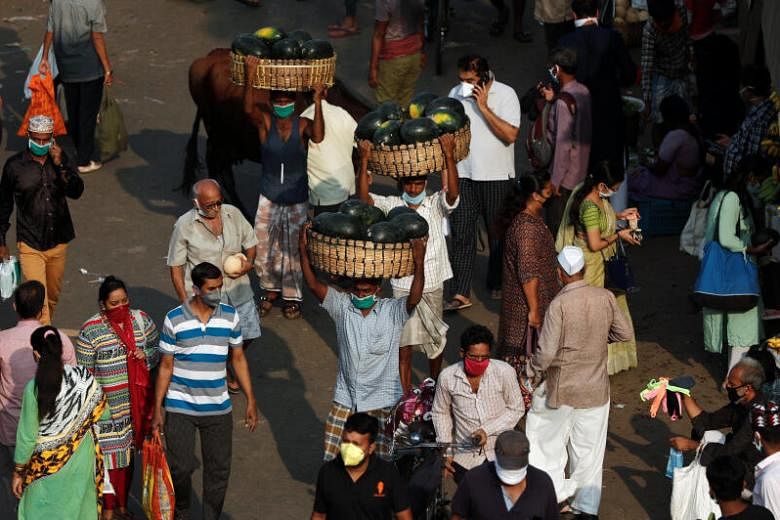

Agricultural Produce Market Committees, which are bulk supply markets in each district for fruit, vegetables, grains, lentils and flowers, were forced to close their gates across the country to prevent overcrowding.

"It broke the whole supply chain between Saturday and Tuesday. We have now asked the government to allow us to open on alternate days," said Mr Rajanna Srikanth, deputy director of wholesale markets in Karnataka.

In Maharashtra, the traders' association negotiated for the market to be open for fewer hours, from 10am to 3pm instead of 7pm.

With markets shut, farmer are forced to dump kilos of fruit and vegetables.

"We are not able to find trucks or rickshaws for hire, because of the lockdown. On top of that, the wholesale markets are shut and traders have no way deliver to the cities," said Mr Veeragangaiah, a farmer from the Karnataka State Farmers Association.

Representatives from every level of the supply chain are in intense negotiations with state and federal ministries and hope the supply will normalise soon.

But the shortage of workers has confounded them. Public transport is suspended across India, and the police in many states stop people on personal vehicles for violating the law.

"We are working with 20 per cent capacity," said METRO's Mr Mediratta.

Thousands of migrant daily wage-earners, who form the backbone of Indian manufacturing, trade and agriculture, are walking hundreds of kilometres back to their villages. After the lockdown, they could not afford food and rent in the cities, and believe they will be more secure in their homes.

Governments have asked them to stay in makeshift city shelters and promised to feed them or give them grain to cook. But as cities begin to face a shortage of food, the promise may be hard to keep.

Mr Vinay Sreenivasa, a social worker trying to organise food for migrants and the poor in Bangalore city, said, "We're in a strange situation where there are people who need food, and there are people who are willing to sponsor it, but there is just not enough bulk supply."