PHUKET (Thailand) • For generations, 71-year-old Ngeem Damrongkaset's ancestors ran long-tail boats off Rawai beach on Phuket's southern coast, where their bones now lie deep in the sand.

Mr Ngeem did that too as a young man and well into middle age.

Today, he still goes out on the boats once in a while with friends or visitors. He likes showing them the place where his father died from a shark bite when he was just three months old.

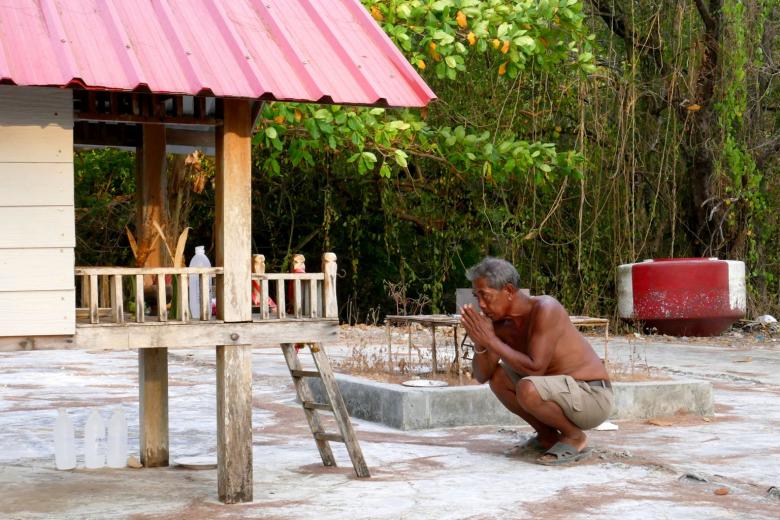

Mr Ngeem is an Urak Lawoi, one of the tribes living off the sea and coastal forests known collectively as the Chao Lay or people of the sea, and also called the sea gypsies.

Of Malay extraction - writers have referred to them as orang laut or people of the sea - and speaking Malayo-Polynesian languages, they live along the coastlines of Myanmar and Thailand on the eastern fringes of the Andaman Sea. Apart from the Urak Lawoi, the Chao Lay also include the Moklen and the Moken.

These three are distinct tribes with their own languages. In Thailand, the Urak Lawoi is the largest of the three, with 4,400 living in Phuket province, which includes dozens of small islands.

In recent years, and now more than ever, the tribes have found themselves squeezed between a way of life that has for generations marked their attachment to land through the burial sites of their ancestors and spiritual shrines, and the inexorable encroachment of development on these lands.

Rawai is the epicentre of this collision. In late January, lean and hungry men with sticks - thugs for hire - arrived to drive the Chao Lay community from land which a company said it had bought and had the papers to prove it.

The Baron World Trade Company wants to build villas on the 5.2ha land on the beach where the Urak Lawoi have their shrine, and where they and the Moken tie their boats.

The Chao Lay community resisted and there was a pitched battle, leaving many injured.

A second confrontation took place on April 11, when men with backhoes showed up, sent by the same company. The community told them to leave, and police had to rush to the spot to defuse a potential fight.

Memories of the mayhem in January are preserved in fading prints flapping in the sun, mounted along a concrete wall the company built to keep the community off the land.

The Urak Lawoi still have access to the shrine to their ancestors, a small wooden structure, through a break in the wall.

Now Thailand's military regime has stepped in with a letter yesterday to Mr Ngeem summoning nine Chao Lay and three other activists to explain their case. The army plans to listen next to Baron World Trade. Colonel Manot Jankiri of the local command was quoted by the Phuket Gazette as saying: "We want justice for both sides."

Adjacent to the land is the village where Thailand's Department of Special Investigation dug up bones to test if they were Chao Lay remains, eventually concluding that they were, and that they dated from over 60 years ago.

The Chao Lay do not own the lands on which their shrine and village sit, but they cite the bones of their ancestors as proof they have long occupied these lands and that they should have the right to remain.

Marginalised for being different

The conundrum in Rawai is a particularly acute example of a traditional community encountering urbanisation and state bureaucracy.

But the Chao Lay's problems go beyond contending with encroachment of their land.

Like the hill tribes in Thailand's north known as the Chao Khao or people of the mountains, they also face a struggle for recognition.

Many Chao Lay have only in recent years been given Thai citizenship, which qualifies them for government-provided healthcare and schooling. There are still a handful without any citizenship.

Thailand's notion of "Thai-ness" is a unitary one, based on commonalities like the Thai language and Buddhism.

The tribes speak their own tongues and practise their own forms of religion or spirituality, and are thus not widely regarded as Thai. Scholars have occasionally applied a new term for them: Thai Mai or new Thais. "We do feel marginal," Mr Ngeem said.

Professor Narumon Hinshiranan, an expert on the Chao Lay at the Social Research Institute at Chulalongkorn University in Bangkok, said: "Because they go by land titles, local people tend to look down on the sea people and side with the landowners."

Mrs Tuenjai Deetes, one of Thailand's National Human Rights Commissioners who has been wrestling with the Rawai issue, said: "They are Thai citizens, but the owners of the land don't see them that way.

"They call them sea gypsies."

As a measure of their marginalisation, in Rawai, of the 20 to 30 stalls in the fish market in the small lane that separates the beach from the huddled houses of the Chao Lay community, only two belong to the community.

Only about 10 individuals in the community are university graduates, said Mr Ngeem, who is a former elected community leader.

The Chao Lay were very much ignored as far as the rest of Thailand and the outside world were concerned, until the devastating 2004 Boxing Day quake and tsunami.

Their closeness to the sea as artisanal fishermen meant they knew what to do when the water receded after the massive quake, minutes before the tsunami hit.

Unlike the thousands of tourists who crammed the beaches of Phuket that fateful morning, the Chao Lay fled inland and survived.

Rights to ancestral lands

That brought more attention to the Chao Lay and their plight of being forced off their ancestral lands.

In Rawai, the Chao Lay are a small community of 252 households, the majority of whom are Urak Lawoi and the rest Moken. They live in slum-like conditions on the margins of Phuket's tourism boom.

The Chao Lay may have lived on this land for at least two generations, but it is owned by others. Government records show that its ownership has changed hands several times. With no concept of land ownership, and until recently having only tenuous rights, the Chao Lay were either oblivious to or had ignored the issue of land ownership.

Phuket province governor Chamroen Tipayapongtada said in an interview: "The problem is their transition into the new world, into the developed world.

"It is the transition from being water people to land people. The first thing they have to face is legality, rights and identity."

He added: "The Chao Lay have longstanding traditions and we are trying to find a solution so they can keep the rights over the lands which are now privately owned or, even in some cases, government land."

There are five Chao Lay communities in Phuket province, with four either on private or government land, he said.

To resolve the land issue for the Rawai community, a site has been allocated on a nearby island for them to resettle in. But they are reluctant to move.

"The site is 2km from the beach," explained Mr Sanit Saesua, 40, a Chao Lay rights activist who still fishes for a living.

"Here, we are just a few metres from our boats."

He added: "The government always talks to us in language that is difficult to understand.

"These disputes have been dragging on since 2009. In the past, people in the community have been tricked into signing documents saying they rent the land that they have lived on for generations.

"There must be 110 court cases of this sort."

Mrs Tuenjai has urged that the courts dealing with the land cases use more than government documents and laws in their decisions. They should consider anthropological evidence and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People, she said. "This is a long story, not just in Rawai but all over Thailand, in which the concept of community ownership clashes with individual ownership."

A way of life is threatened

Another fear among the Chao Lay is the loss of their traditional way of life as fishermen.

Indeed, Prof Narumon fears the people of the sea may end up becoming cheap labour and unable to live with dignity.

On Rawai beach, in the shade of a banyan tree, Mr Sanit, an Urak Lawoi, sat making his fish traps.

The traps made with rattan and wire mesh are the size of minivans, big enough for a man to stand up in.

They are placed on the seabed for a few months.

The Urak Lawoi and Moken fishermen visit the traps daily, remembering where they are placed purely through visual orientation.

They put on snorkelling masks and, breathing air from a hose connected to an air pump on their boat, they dive to depths of 3m to 6m for up to half an hour at a time, netting the fish caught in the traps.

They then use air from the hose to inflate a plastic bag and attach the bag to the nets, using it to float them up for the waiting boat crew to haul them in.

But fewer and fewer practise this form of fishing now, Mr Sanit said, his hands working deftly as he twisted the wire mesh.

"Around 20 per cent of fishermen are still going out to fish, but many have given up and have gone to seek jobs outside fishing," he said.

As on land, the Chao Lay also find themselves being constrained at sea.

They often get arrested and handed heavy fines for straying into recently established marine protected areas or island national parks.

"We don't have enough money to pay fines," said Mr Sanit.

The community, with the help of academics like Prof Narumon, is negotiating fishing and forest produce rights with the Department of National Parks.

Only eight people in the Chao Lay community operate tourist boats and can earn 1,500 baht (S$58) a day, but days go by when they do not earn anything, he said.

Fishermen's earnings also vary.

A good day's haul can fetch several thousand baht, but it has to be divided among the crew - typically one or two divers, one boatman who also operates the air pump, the boat owner or captain who keeps an eye on all and helps all, and a young helper who hauls gear, sorts fish and puts them in ice, and swabs the decks.

"Deep-sea fishing is freedom,'' Mr Sanit said.

"But we don't know how long we can maintain such a life."

For the Urak Lawoi, says Mr Sanit, dignity is in life in the sea, and on the land where they have lived for generations.

He looked around.

"My ancestors are buried here," he said simply.