In its editorial on Sept 20, 2015, the newspaper says it is strange that Jakarta has not taken up Singapore's help to put out the fires.

It is quite clear that with the unrelenting forest fires and the toxic air pollution imposed on local residents, we could use all the help available to extinguish the fires as soon as possible.

It seems strange and deeply hurtful for affected Indonesians and people in neighbouring countries that the government so far has not taken up the offer from Singapore to help put out the fires.

The new chief of the National Disaster Mitigation Agency (BNPB), Rear Admiral (retired) Willem Rampangilei, has said, as we reported on Friday, that at least 30 days would be needed to put out fires, particularly in Riau, Jambi, South Sumatra, and West and South Kalimantan.

Decision makers and the public in Jakarta do not suffer the exposure around the clock, for months on end, to the suffocating air that stings the eyes - forcing residents to stay indoors, leading to the virtual crippling of several areas, inevitably also in Malaysia and Singapore - where the Formula One auto race is scheduled for Sunday (Sep 20) .

Unlike affected residents, many of us can afford to feel hurt pride or take offence at whatever Singapore officials say; some among us even hailed Vice President Jusuf Kalla who earlier chided Singaporeans complaining about Indonesia's haze, despite enjoying the nice air for most of the year.

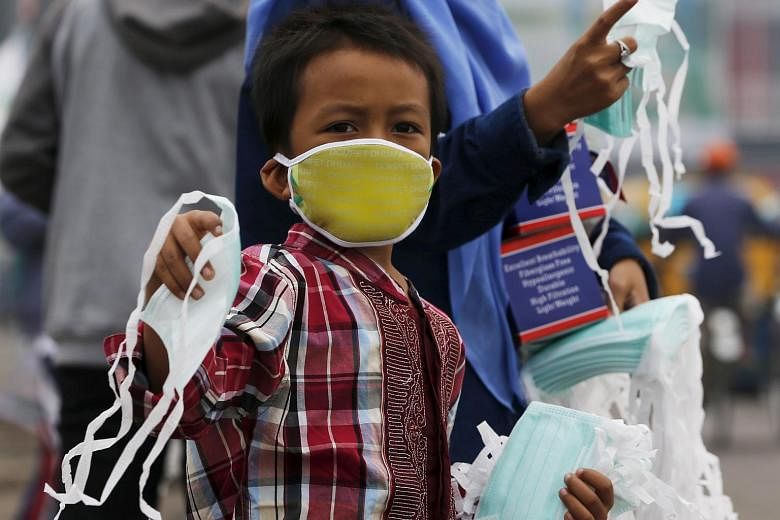

An infant and a junior high school student died in Jambi after being treated for breathing difficulties; thousands of others have needed medical treatment and several students in Pontianak, West Kalimantan, passed out at school on Wednesday.

President Joko "Jokowi" Widodo has reiterated that law enforcers should not hesitate to drag to court and punish perpetrators of forest fires including companies that order the burning; those guilty could face a maximum fine of Rp 10 billion (S$one million) and up to 10 years' imprisonment for violating the Plantation Law.

His new chief security minister Luhut Binsar Pandjaitan, a retired general, is facing his first test case, being entrusted to oversee efforts to stop the fires.

He has told governors to assess concessions and whether some may have to be revoked because it was a mistake to have issued permits for plantations on areas of peat soil.

But the government would avoid such confusion if permits were based on regulations that govern such plantations.

Regardless of law enforcement and the likely slow assessment process of concessions, local residents and everyone else affected need immediate help from any party to stop the smog and fires right away, which is harder to achieve across the currently dry and fire-prone peat land, where most of the fires are occurring.

Frustrated residents say that over the past 18 years the present, pervasive haze has been the worst.

They do not care less about national pride; instead residents wonder if anyone cares and whether the government actually exists. Immediately asking for our neighbours' help, in their eyes, would be the very least the state could do as an urgent short-term step.

"It is as if it's considered natural that the fires and smog must occur each year," said Helda Khasmy who leads Seruni Riau, the Riau chapter of the Indonesian Women's Union, part of the women's movement demanding action against the culprits behind the haze.

The movement blames the annual fires and smog squarely on the "monopoly of land ownership" of large plantations, covering millions of hectares in Riau alone, which, they allege, leads to rampant, reckless land clearing of dry peat land.

Several subsidiaries of large business groups have been named by police as suspects and at least one has been convicted and fined by the Supreme Court.

But, among others, the managing director of Sinar Mas Group's Asia Pulp and Paper, Aida Greenbury, has said, "We guarantee that our suppliers are not burning the land as we have applied strict prohibitions on such practices."

Company managements say they have their own firefighters and prevention programs including public education, to protect their plantations and surrounding areas; but many newcomers, they say, are far less understanding of the traditional methods of land clearing, which include burning.