On April 3, 1950, temple gongs rang out across Siam as he sailed into Bangkok aboard the Royal Thai Navy's flagship Sri Ayutthaya.

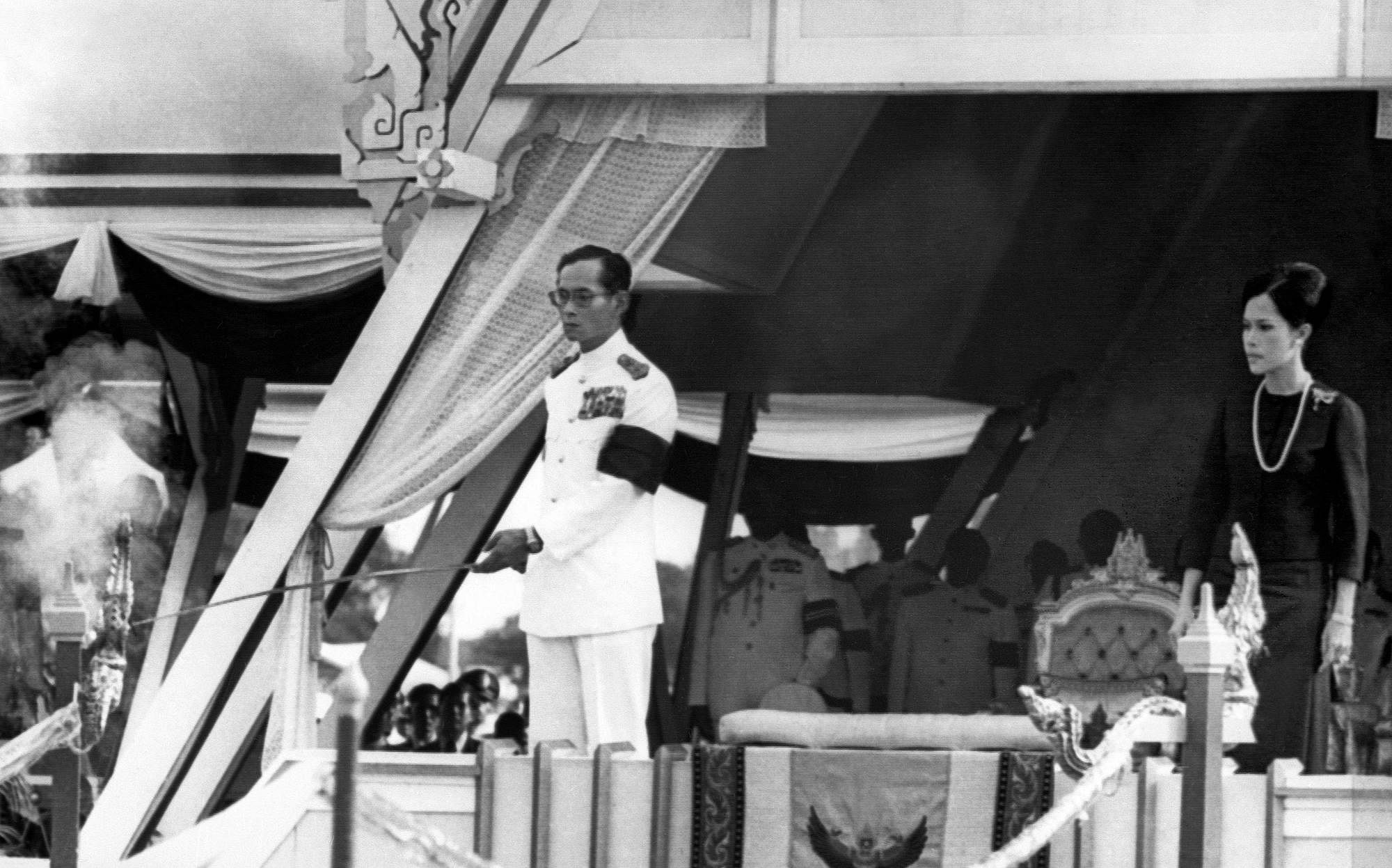

Thousands of fishing boats rushed out to greet 22-year-old Bhumibol Adulyadej, who was returning to be crowned King. On April 28, he married Queen Sirikit. When he took his place on the throne on May 5, 16 warplanes flew above dropping rose petals.

Over the subsequent years, the soft-spoken monarch would transform from a privileged United States-born, European-educated young man into a father figure for a nation of more than 60 million people.

He navigated the nastiness of the Cold War and regional conflicts, travelled the length and breadth of the land earning the affection of millions of his subjects, and survived Thailand's cut-throat politics with a soft-spoken, aloof detachment.

And Thailand grew and changed from a poor agricultural nation surrounded by instability and war, into a vibrant modern economy and one of the world's top tourism destinations, its gross domestic product many times more than that of its immediate neighbours' combined GDP.

FROM NADIR TO APEX

Born in Cambridge, Massachusetts, on Dec 5, 1927, Bhumibol came to the throne in 1946 when he was 18, following the still controversial shooting death of his older brother King Ananda Mahidol in Bangkok the same year.

The brothers were very close. The loss of Ananda, who was shot through the head while lying in bed with a Colt .45 that he kept by his bedside, devastated Bhumibol who had just been with his brother, and was on the scene again only minutes after the shot.

Three palace officials were later convicted and executed on charges of plotting to assassinate Ananda, but what exactly happened has never been properly explained.

Bhumibol himself later said enigmatically: "It was not an accident, not a suicide, but what happened is very mysterious...it is political."

As he was studying in Switzerland, Bhumibol went back there to complete his education. When he returned to Siam in 1950 for his coronation, the monarchy's power was shaky, but the institution had a strong position in Siamese culture, and the monarch was still seen as the last refuge in times of turmoil. The country was roiled by internal conflicts and coups d'etat, but the young king inherited a reservoir of goodwill. An estimated 500,000 Thais had turned out for his brother's funeral.

Overseas, Thailand had an ally in the US, with their treaty dating back to World War II. A strong Thai monarchy was seen as the best bulwark against the spread of communism.

At home, the machinery of the state elevated the monarchy to its highest stature since the glory days of King Chulalongkorn, also known as Rama V, who ruled from 1853 to 1910. In 1958, military dictator Field Marshal Sarit Thanarat, who ran Thailand from 1957 to 1963, brought back the ritual, pageantry and protocol surrounding the monarchy from near-obscurity. Essentially, after 1946, the monarchy was reconstructed, to recover from nadir to apex.

The idea of "Nation, Religion, King" as core values of the Thai state was reinforced. Long after Thanarat himself was gone, generals and prime ministers still had to prostrate themselves before King Bhumibol, even kneeling before his portrait when receiving appointments sealed by the palace.

WORKING KING

But it was King Bhumibol's own work that built his moral authority.

In Europe, he and his friends would play jazz music in the family villa in Lausanne through the night. He met Elvis Presley, jammed with Benny Goodman and composed his own music. He sailed a yacht. He spoke several languages. He liked painting and photography.

Back home, especially in his early years on the throne, he actively engaged with his people in travels throughout the country.

The King's convoy, filled with engineers, doctors and agricultural scientists, travelled about 50,000 kilometres a year in Land Rovers and on foot across rivers and up and down muddy hillsides. The King and Queen gave out tens of thousands of blankets, towels, clothes and school uniforms to Thais every year on their tours.

The young monarch had a Renaissance mind, taking an interest in subjects from science to environment to engineering, and even to cloud-seeding to induce rain. Official photographs invariably showed him as a working king, with a camera slung around his neck.

He was most interested in water management and started big and small irrigation projects. Back in Bangkok, usually alone in his study surrounded by communications equipment and maps, he pored over books and drew up proposals and designs. He kept in touch with the government through his own radio sets.

The idea of service had been instilled in him by his mother Mom Sangwan in Switzerland. When the brothers received any money, they always had to put a percentage into a box. This would be given later to the poor.

Today, the Thai monarchy sits on the enormous wealth of the Crown Property Bureau, estimated by Forbes magazine in 2012 at more than US$30 billion. The government has taken pains to explain that the wealth belongs the nation, not the monarchy.

MORAL AUTHORITY

Constitutionally, the King of Thailand and the royal family remain above politics. But the King wields great extra constitutional authority. The government's major decisions are taken in the name of the King once he has ratified them. The army swears its oath of loyalty to the King; the judiciary takes office in the name of the King. The government itself is appointed or endorsed by the King.

Thailand's constitutions stipulate that the "The King shall be enthroned in a position of revered worship and shall not be violated. No person shall expose the King to any sort of accusation or action."

King Bhumibol took care to appear both aloof and even-handed during the occasional savagery and multiple military coups of Thai politics.

In October 1974, he told the Far Eastern Economic Review in an interview: "I became King when I was quite young. I was 18, and very suddenly, I learned that politics is a filthy business."

In 1979, in a rare interview for a BBC documentary, he acknowledged - impassively as usual yet with a tinge of irony - that everything he did was inevitably viewed through a political lens.

By then the popularity of the monarchy had been restored to what Paul Handley in his 2006 book, The King Never Smiles, called "the most potent political force in Thailand".

On Oct 14, 1973, students demanded the end of the regime of military dictator Thanom Kittikachorn; the King opened the gates of the Chitralada Palace in Bangkok to allow them to flee a murderous crackdown. Later he appeared on television to announce that the dictator had resigned. The Thanom regime was over.

In 1992, after days of killings on the streets of Bangkok as troops under the command of yet another military dictator, Suchinda Kraprayoon, cracked down on pro-democracy crowds led by retired general Chamlong Srimuang, King Bhumibol summoned the two men. On live TV, the world saw the two generals respectfully sitting at his feet. He admonished them to stop the violence.

"Our country does not belong to any one or two persons, it belongs to everyone," he told them. "There will only be losers," he warned.

The spectacle served to cement his moral authority. Soon after, the violence ended and General Suchinda gave way.

Analysts and writers have argued over whether King Bhumibol did nothing, too little, or too much in times of crisis, and whether he could have done more when blood was being spilled in the streets of Bangkok - especially after 2006, when the monarchy was increasingly perceived by many Thais as having taken sides in the country's deep political and class divide, and the King himself grew old and frail.

But when he did intervene - in 1973 and in 1992 - he undoubtedly prevented more loss of life. And he did it while treading a fine line in an environment in which, often, contesting power centres all claim to be fighting in the King's name, and regularly accuse enemies of disloyalty to the King - a potent and emotional charge.

At times this mantle seemed to sit heavily on him, and as he grew old, encircled by the apparatus of his position, he also appeared to grow weary.

SOUL OF THE NATION

The mysterious death of his brother Ananda long irrelevant, King Bhumibol had had no scandals, which helped burnish his image as a father figure. His own family was not without drama. Of his three daughters, Princess Ubolratna Rajakanya, married a "commoner" American against the wishes of her father. She was stripped of her royal title. Later divorced, she returned to Thailand for good in 2001 with her title restored. One of her three children, Phum Jensen, was killed in Thailand in the December 2004 tsunami.

The personal life of his only son and heir to the throne, Crown Prince Maha Vajiralongkorn, has occasionally been the subject of gossip and innuendo. In late 2015, he divorced his third wife Srirasmi. A crackdown on her family, invoking the controversial Article 112, saw several of family members jailed.

Article 112 is the harshest lese majeste law in the world. It forbids insulting the King, Queen, Heir or Regent. Its application has widened, and criticism of the law is often conflated to be deemed criticism of the monarchy. Thus the institution remains opaque and outside the scope of public debate. Under the royalist military regime that seized power in 2014, prosecutions under Article 112 went up sharply, driving a new wave of Thai dissidents abroad.

Kukrit Pramoj, who was prime minister in the mid-1970s during a brief period of parliamentary democracy, told the BBC in 1979: "The monarchy is the soul of the Thai nation.

"The King is more than a ceremonial head. Thais are very clannish. First of all he is the head of the clan. He is the father of the very big family of Thais. And he is the source of Thai culture. Everything emanates from him. Good manners, way of living, the sort of thoughts and the way of thinking which is regarded as the best of Thai thinking. Even the Buddhist religion, to us, seems to emanate from the King and the monarchy."

King Bhumibol's death is, for Thais, a once in a lifetime event; for the country as a whole, regardless of political beliefs, it is at a deep, visceral level the end of an era. Establishment insiders like Mr Anand Panyarachun, twice-appointed prime minister to steer the country through turmoil, have stressed that the respect in which the monarchy is held, is specific to the monarch.

In June 2016, Australian National University academic Nicholas Farrelly wrote: "When King Bhumibol is no longer on the throne, this system will face further tests."

For decades, King Bhumibol was the face of Thailand in the larger world, seamlessly blending ancient tradition with modernity. From the highest Bangkok penthouse to the lowliest country shack, pictures of Bhumibol mingled with family portraits.

Thailand may essentially be a feudal country run by patronage networks and plagued by a notoriously corrupt political class, but for millions of ordinary Thais, their enigmatic King Bhumibol was thoroughly internalised and idealised as a unifying father figure who rose above it all.