A marvellous old piece of India's heritage - the brocade sari woven by hand in Benares over centuries and which used to be coveted by Indian women - is getting a makeover for modern times.

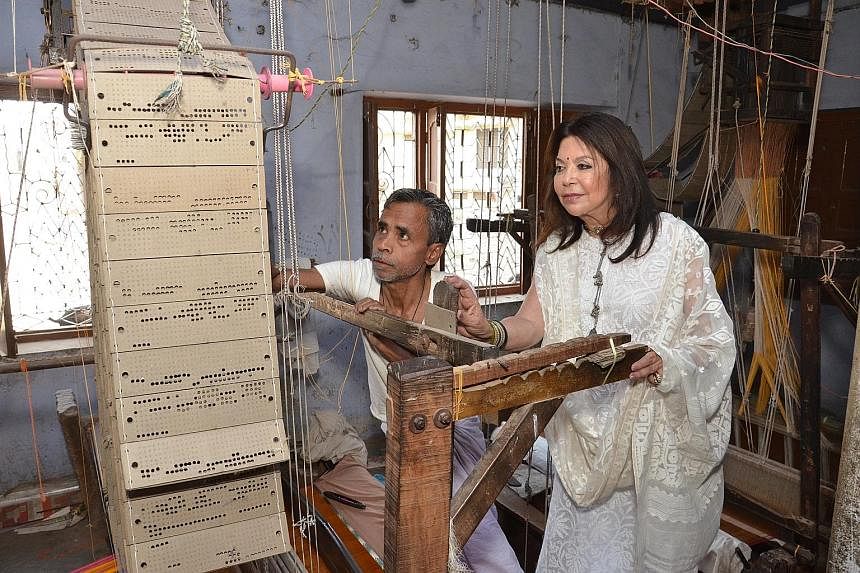

About two dozen top names in the Indian fashion industry went to the ancient Hindu holy city of Benares, now called Varansi, on the banks of the Ganges in May to meet the weavers whose skills are dying out because of falling demand.

Those who turned up, including designers Tarun Tahiliani, J.J. Valaya, Anamika Khanna, Wendell Rodricks, Rohit Bal, Neeta Lulla, Ritu Kumar and Anju Modi, have promised to give the weavers new design ideas for the sari. They have also agreed to base their next collections on it.

"Our precious heritage is being lost," said Ms Modi. "The day the last weaver loses this skill, it will be gone forever. As designers, we cannot stand by and let the country lose this beautiful craft."

In addition, they will attempt to popularise the fabric abroad, an effort which will be supported by the Textile Ministry. Prime Minister Narendra Modi's constituency is Benares and he has pledged to revive the handloom industry.

Until about 20 years ago, the Benares silk sari enjoyed a near-mythic status, one that dates back to the 17th century. It reached its heyday in the 18th and 19th centuries, thanks to the Mughal emperors who loved its sumptuous qualities. Increasingly intricate designs were crafted for them, using real gold and silver threads.

Since then, the Benares sari has occupied pride of place in an Indian woman's wardrobe. A few of them were in every bride's trousseau. It would each cost around 15,000 rupees (S$320) to more than 100,000 rupees but that was never a deterrence. Women treasure them like heirlooms, even if they rarely wear them because they are so heavy.

In 2001, however, Benares became a dumping ground for cheap silk yarn from China when India lifted restrictions on it. Since then, the market has been deluged by saris costing a few dollars made from Chinese silk which traders sell to unknowing customers as "hand-woven Benares silk saris".

Handloom weavers struggled to compete with the prices. Some even began weaving a stiff fabric and using poor designs and garish colours, putting off potential buyers.

"The Benares sari became associated with middle-aged women - something stiff and formal and worn only on special occasions," said Ms Shaina N.C., a Bharatiya Janata Party politician and fashion designer who is spearheading this latest effort to save the Benares sari.

Unable to cope with falling demand, weaver families (the entire family is involved in producing the sari in this cottage industry) have been abandoning the craft.

The sons prefer to work in call centres or as drivers where they can earn US$188 to US$235 (S$250 to S$320) per month instead of the fluctuating fortunes of their ancient craft, with salaries ranging between US$60 and US$100 a month.

Mr Arif Hassan, 52, for example, has been a weaver since childhood. He learnt his craft from his father who learnt it from his. Now with four children of his own, Mr Hassan cannot support them on his income of US$2.50 a day.

"I know this work is in our blood but my sons will not continue this work," he said. "Even being a rickshaw puller or a factory worker will be better than this."

It is not known how large the weaving community in Benares was under the Mughals but it is estimated that up to one million weavers and their families - children start helping at the age of six or seven - now work in the cottage industry.

Although designers have been helping weavers with new designs, the initiative to bring 50 designers and weavers together to save the sari was Ms Shaina N.C.'s idea.

If this is to happen, young Indian women need to start buying.

"Girls want something easy to wear," said designer Ritu Kumar.

"Weavers used to make lovely soft fabric but now, they produce stiff, bulky fabric. I've been helping them get back to that soft fabric and making sure they use a soft, dull gold thread instead of the shiny, bright yellow they were using."

Ms Divya Gupta, a 28-year-old advertising executive in New Delhi, said she loves opening her mother's trunk to look at her old Benares saris but never wears them.

"I associate them with aunties of a certain age and size," she said. "The kind of Benares silk I would like to wear would have to be light and easy to carry off on ordinary, everyday occasions, not just weddings and banquets."

But concern over the disappearing sari prompted two female friends in Bangalore to start a campaign, 100SariPact, calling on women to take a pledge to wear a sari twice a week, or 100 times a year. Their campaign, which started in April, has caught on.

Women are posting pictures of themselves in saris on Facebook and Twitter.

Said Mrs Kumar: "This is the generation that the weavers need to catch fast."