When you tuck into your next meal, spare a thought for those going hungry on World Food Day across Asia today.

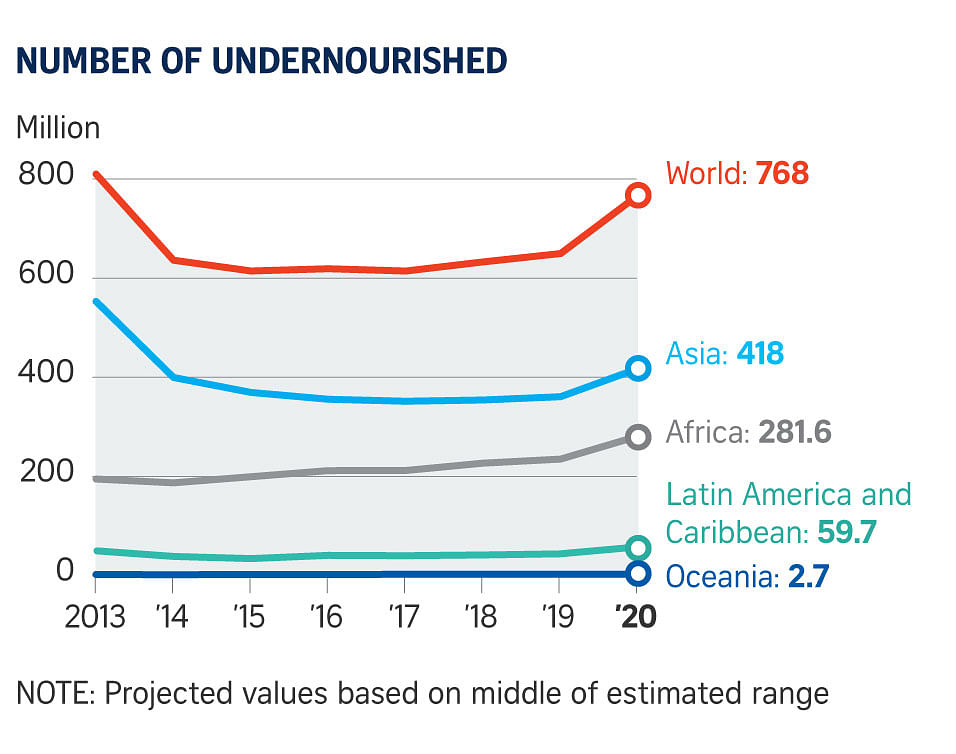

Asia accounts for the bulk of people who are undernourished around the world today, with 418 million people making up over half of the hungry mouths worldwide.

The majority are in South Asia, which accounts for 305.7 million people. South-east Asia follows with 48.8 million people, and West Asia with 42.3 million, according to the State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2021 report by the United Nations' Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO).

In 2019, before the Covid-19 pandemic erupted, Asia was assessed to have 361.3 million undernourished people.

"Being in a state of acute food insecurity means that families are faced with really tough decisions - they may be forced to skip meals, eat less nutritious foods, prioritise children over adults at mealtimes, fall into debt to buy food, (or) sell off key assets to make ends meet," the UN's World Food Programme (WFP) spokesman James Belgrave told The Straits Times.

"Their nutrition will likely suffer. Children may become wasted - too thin, or stunted, too short - with impacts that will last their whole lives," he added.

Mr Belgrave said most countries in Asia where the WFP operates have seen increased food insecurity due to the socio-economic fallout and economic impact of the pandemic, and extreme weather events such as droughts, floods and storms.

"This may have affected particular segments of the population, in particular urban centres, slums in major cities in the region," he said.

Professor of applied economics Prabhu Pingali, director of the Tata-Cornell Institute at Cornell University, noted that global food production has not been affected by the pandemic and so hunger is being caused by loss of incomes.

"None of the major food exporting countries has seen a drop in production. India has seen record harvests of food grains in 2020 and 2021. Food supplies have not been a problem in most Asian countries.

"The primary problem has been access to food due to loss of employment, primarily among low-wage migrant workers who were forced to return to their home villages," he said.

Prof Pingali also cautioned against over-reliance on hunger estimates.

"Global hunger estimates are best for looking at long-term trends but not for assessing the number of people affected by an immediate shock. Moreover, the hunger numbers provided by the UN agencies are based on calorie adequacy rather than a measure of a balanced diet which includes proteins, minerals and vitamins. So it does not measure 'hidden hunger' or micronutrient malnutrition," he said.

Hunger pangs

The situation in some countries looks increasingly desperate. Over 20 million Filipinos - or one in five people - said they went hungry in the first three months of the year, twice as many before the pandemic, according to a survey by Social Weather Stations.

They said there were days when they did not have anything to eat, or they had just one meal a day.

"We can't provide food for an entire family. Yet, people line up for food, even if they'll just be getting enough for one serving. That means they're desperate," Mr Jomar Fleras, executive director of the non-profit Rise Against Hunger, told The Straits Times.

His organisation has the largest network of soup kitchens and feeding programmes in the Philippines.

Housewife Lara Villalon, 33, said her family went through a food security scare when her husband, a casino worker, lost his job during the pandemic.

"Luckily, we had our savings and a backyard garden. I also began to sell food online. Those helped tide us over," she said.

The poverty rate in Malaysia has also considerably worsened after repeat lockdowns that have badly affected income streams for many informal workers.

The government revealed last month that Malaysia's absolute poverty rate rose to 8.4 per cent last year compared to 5.6 per cent in 2019. This translated into 580,000 households slipping into the lower-income bracket.

Economist Muhammed Abdul Khalid, the managing director of research outfit DM Analytics, said that Malaysia is already facing a national crisis in terms of food access and malnutrition among vulnerable households. "20 per cent of Malaysian children are malnourished, this is the biggest issue that will impact us in the long run," said Dr Muhammed.

Hunger is particularly acute in India, which slipped seven spots to be ranked 101 among 116 countries in the Global Hunger Index 2021 released this week.

It was placed in the "serious" hunger category and ranked behind Nepal (76), Pakistan (92) and Bangladesh (76). The report stated that 15.3 per cent of India's population is undernourished and 17.3 per cent of children under five suffer from child wasting.

"People have been severely hit by Covid-19 and by pandemic-related restrictions in India, the country with the highest child wasting rate worldwide," the report said.

Millions of people remain excluded from the public ration distribution system because the government uses outdated population data to calculate beneficiaries. A recent analysis showed that over 100 million people entitled to food rations are not getting them.

Another event that affected food security for some in India was the swarms of locusts that invaded several parts of the country and Iran, as well as neighbouring Pakistan, last year. Scientists say that extreme temperatures in the region assisted the breeding of the insects, which also devoured crops on a large-scale in Africa.

Sharing is caring

For a number of low-income families in Thailand, food or daily necessities distributed by non-government organisations (NGOs) have been a godsend.

"Without them, we wouldn't have anything to eat," said Madam Somporn Boonnoi, 46, a widow who has two children aged 10 and 15.

Gesturing to the bags of instant noodles and dry food in her home in the Klong Toey slums, Madam Somporn added: "It's the only way we can survive."

The pandemic pushed almost 800,000 more Thai people into poverty last year, a study by the Thailand Science Research and Innovation found.

And with Covid-19 curbs - only recently lifted - that locked down cities, shuttered businesses and restricted travel and movement, thousands have lost their jobs or had their working hours and wages cut.

While the government has implemented measures to cushion the financial blow, many grassroots groups and NGOs have been plugging the gaps by distributing food and necessities to the needy.

In Indonesia, the centuries-old, widely-believed notion that it is "a major sin to leave your neighbour hungry" has long made the country relatively resilient against hunger, but undernourishment affects a large swathe of the population.

"Indonesia doesn't have any cases of famine. Our problem is undernourishment, which accounts for about 8 per cent of the population," said Mr Agung Hendriadi, the head of Indonesia's food security agency.

"Our challenge is distribution, not availability, of food. We are more than 17,000 islands and there are regions with surplus of food and others with deficits. We are consistently monitoring to fill any gap."

Nevertheless, observers noted that unreported food shortages in the world's largest archipelagic nation could be possible from time to time.

Complex issue

Hunger is also a growing issue in Myanmar as it grapples with both the pandemic as well as the political and economic free fall triggered by the Feb 1 military coup.

Financial institutions have been debilitated by the run on banks and the junta has tried to staunch this by limiting cash withdrawals.

WFP country director Stephen Anderson warned last month that more people could face "extreme deprivation" in Myanmar.

In April, the UN agency projected that the number of people going hungry could double to 6.2 million in the next six months.

Most at risk are villagers displaced by armed conflict flaring up between the military regime and "people's defence forces" resisting its rule. In areas where it faces the strongest resistance, the military inflicts collective punishment by destroying homes, food supplies and livestock.

Global charity Save The Children warned on Oct 4 that a large portion of the over 76,000 children forced to flee their homes since the coup are living in the jungle and many families are sharing just one meal each day.

In urban areas and where the armed conflict is not that intense, residents are struggling with unemployment and inflation.

Mr Lay Win, 43, was forced to stop driving his taxi last month because he couldn't find any customers. He has withdrawn all his savings and spends only on necessary meals for his family of three.

"We can only spend a little each time as I am jobless," he told ST. "We have seen and heard about a lot of other families in difficulty, who have had to sell their possessions to buy food."

The food situation in sanctions-hit North Korea - ranked 96th in the Global Hunger Index - is also dire.

Leader Kim Jong Un in April told his people to prepare for "another more difficult Arduous March", using the term for the deadly famine of the 1990s to refer to the severe economic difficulties faced by the country.

He admitted that North Korea is facing the "worst-ever situation" - severe floods that ruined farmland and blistering heat that killed crops, unrelenting UN sanctions, as well as trade and aid from China cut off due to pandemic-induced border closures.

North Korea monitoring groups have not reported signs of mass starvation, but anecdotal evidence suggests people are suffering from the lack of food.

The FAO and WFP had also warned in July that North Korea would face a food shortage of around 860,000 tonnes this year, equivalent to about 2.3 months worth of food.

Hidden hunger

Even in wealthy Japan, food banks are being run for the poor in many major municipalities.

However, the societal stigma of losing pride or face has been a major hurdle stopping many who need help from asking for it. Some NGOs have stepped in to fill the gap and help ensure that food reaches those in need.

In a report by Agence France-Presse earlier this year, one former construction worker said: "This doesn't get reported much in the media, but many people are sleeping at train stations and in cardboard boxes. Some are dying of hunger."

Poverty statistics from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare indicated that 15.4 per cent of the population were living below the income threshold of 1.27 million yen (S$15,000) assessed as the poverty line.

Meanwhile, China has ostensibly come a long way from the devastating famine of 1959 to 1961 that starved tens of millions of people to death.

According to the WFP, the country has helped cut the global hunger rate by two-thirds after hitting its Millennium Development Goal of halving the number of hungry people by 2015.

The latest Global Hunger Index ranks China, along with 18 other countries, as having the lowest hunger levels among 116 nations.

But there remains a large nutritional gap between the rural poor and the urban middle-class in China. The WFP says nearly 150.8 million people are malnourished.

In South Korea, there is a low level of malnutrition at just 2.5 per cent.

The country runs some 450 food banks to help the needy, especially the elderly aged 66 and above, of whom 44 per cent are poor.

However, with 197 of these free food outlets shut down due to social distancing restrictions, a growing number of people are left stranded.

Official data showed that 345 people died of malnutrition last year, most of them elderly. This is higher than the 231 in 2019 and marks the first time in 20 years that the figure exceeded 300.

DongA Ilbo newspaper said in an editorial that it is "shocking" to see hundreds of people dying of starvation in such an advanced country and called on the government to "close the gap" in the welfare system.

A global problem

On a global level, the economic hardship caused by the Covid-19 pandemic pushed 83-132 million more people into chronic hunger last year, said FAO.

Currently, between 720 million and 811 million people are going to bed hungry almost every day.

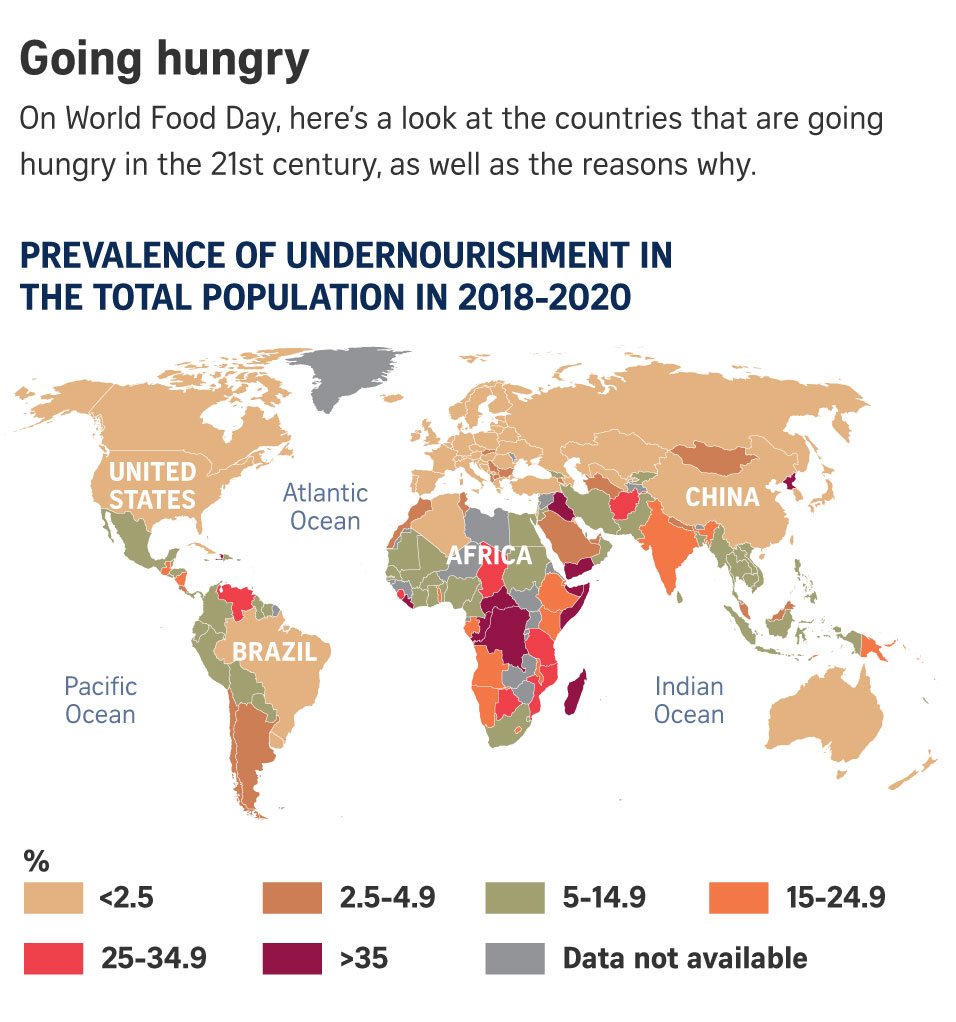

According to the Global Hunger Index, the nations facing the most severe nutritional concerns are Somalia, Syria and South Sudan.

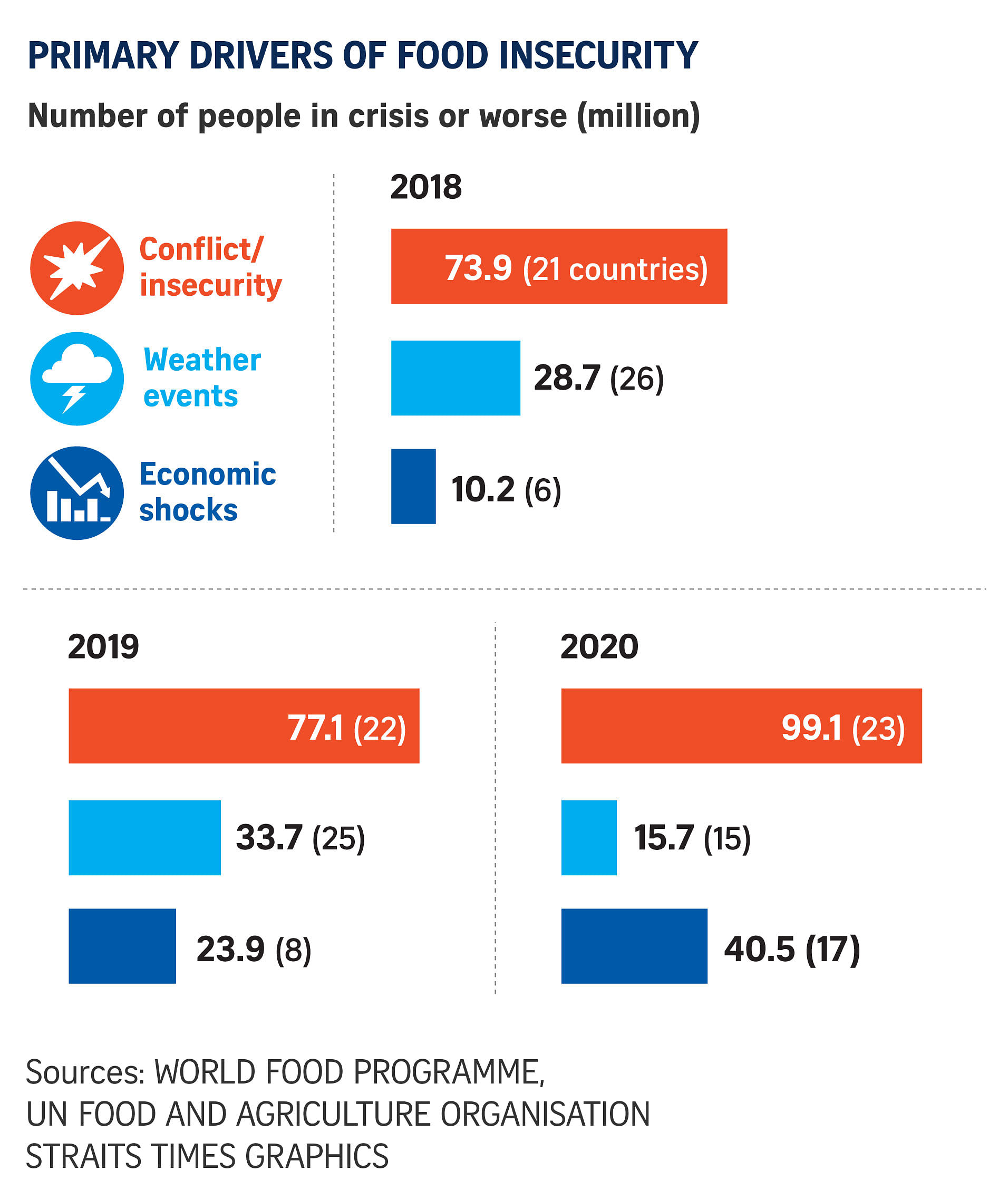

Hunger worldwide stemmed from three main causes: economic shocks such as those caused by Covid-19), adverse weather events such as flooding or droughts, or conflicts and insecurity as seen in Myanmar.

While some of these events can be averted or mitigated, many are impossible to prevent.

While there has been a steady increase in moderate food insecurity (being unable to eat a balanced diet) or severe food insecurity (going without eating for a day or more) around the world since 2014, the rise last year was equal to the previous five years combined, according to FAO.

Moderate or severe food insecurity had been rising from 22.6 per cent in 2014 to 26.6 cent in 2019.

But as the coronavirus rampaged across the globe, nearly one in three people worldwide (30.4 per cent) - or a total of 2.37 billion - do not have adequate food. That is an increase of 320 million people in just a year.

"The pandemic has had a huge impact on food security globally. Measures put in place to control the spread of Covid-19 had a massive ripple effect across economies globally, jobs dried up, food prices shot up, and livelihoods vanished. Food supply chains were also affected meaning less food was available on the market," said Mr Belgrave.

"Because of this, families are finding it harder to put healthy food on a plate, child malnutrition is threatening millions, and famine is still looming," he said.

"Covid-19 has also ushered hunger into the lives of more urban communities while placing the vulnerable, such as refugees, people caught in conflict, and those living at the sharp end of climate change, at higher risk of starvation," he added.

- Additional reporting by Raul Dancel in Manila, Ram Anand Subbarao in Kuala Lumpur, Debarshi Dasgupta in New Delhi, Tan Hui Yee in Bangkok, Tan Tam Mei in Bangkok, Wahyudi Soeeriatmadja in Jakarta, Chang May Choon in Seoul, Tan Dawn Wei in Beijing and Walter Sim in Tokyo