-

TIMELINE OF HK'S RETURN TO CHINESE SOVEREIGNTY

-

1982: China and Britain begin talks on Hong Kong's future.

1984: China and Britain sign the Joint Declaration that sets out the conditions for the handover of Hong Kong to China in 1997. Under the "one country, two systems" principle, Hong Kong is to retain its capitalist system and lifestyle for 50 years after the handover.

1990: China's Parliament, the National People's Congress, adopts the Basic Law, Hong Kong's mini-Constitution.

1992: Hong Kong's last governor Chris Patten proposes democratic reforms to broaden the voting base in elections.

1997: Hong Kong returns to the Chinese fold with former shipping tycoon Tung Chee Hwa as its Chief Executive. The Chinese undo reforms put in place by Lord Patten.

2002: The Hong Kong government proposes a new anti-subversion law.

2003: About half a million Hong Kongers march on July 1, the anniversary of the handover, in protest against the anti-subversion Bill, which is subsequently withdrawn.

2007: Beijing says it will allow Hong Kongers to elect the Chief Executive directly in 2017 and legislators in 2020; pro-democracy activists are disappointed with the drawn-out timescale.

2012: Hong Kongers take to the streets to protest against a proposal to introduce mandatory patriotic education in schools. The proposal is later withdrawn.

2014: Beijing rules that candidates for direct election of the Chief Executive should be vetted by a committee and that the Chief Executive would have to be appointed by the central government. This sparks protests by pro-democracy Hong Kongers who want greater freedom to choose their leader.

2015: The Legislative Council rejects proposals for direct election of the Chief Executive.

2017: Ms Carrie Lam is elected as the new Chief Executive by a 1,200-member committee.

20th anniversary of the Hong Kong handover

Hong Kong handover: 'One country, two systems' shaky two decades later

China-HK gulf has widened since handover, with opposing views of the city's autonomy

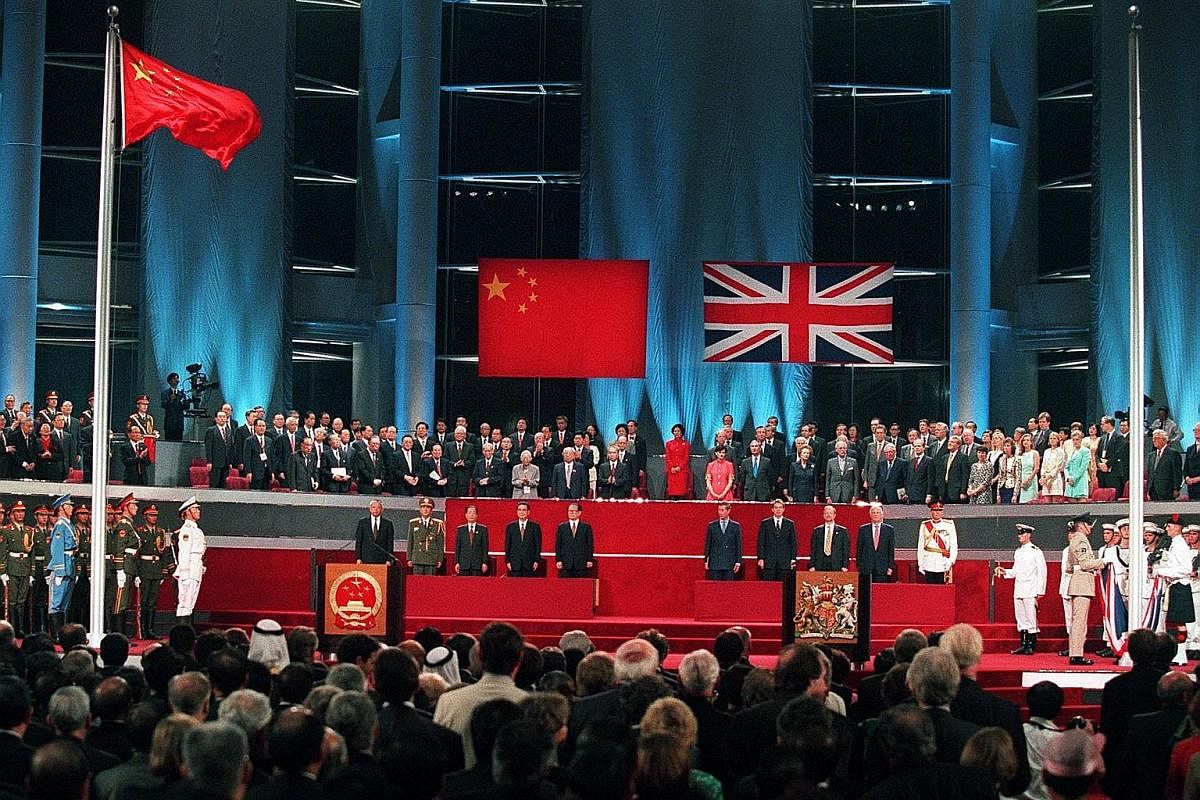

The heavens opened up on June 30, 1997, the day Hong Kong was to return to the motherland China at the stroke of midnight, after 155 years of British rule.

But the Chinese did not see it as rain on their parade.

"It was raining the whole day of the handover ceremonies, but I am sure all Chinese in the world felt this was a refreshing shower, washing away China's humiliation," said then Chinese foreign minister Qian Qichen, who took part in the ceremonies in the city.

Mr Qian, who died last month, was referring to what is now known as China's century of humiliation, starting from the first Opium War in 1839-42 that the Qing rulers fought with the British and lost. This defeat led to the ceding of Hong Kong island to Britain, under the Treaty of Nanking.

It was the first of several unequal treaties between the weak Qing Dynasty and foreign powers that gave these powers jurisdiction over Chinese ports and cities, the "carving up of the Chinese melon". China ceded the Kowloon peninsula to the British in 1860 after the second Opium War, and in 1898 leased the New Territories, which made up 90 per cent of the Hong Kong territory, to the British for 99 years.

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) under Mao Zedong recovered most of the territory lost by the Qing rulers except for Hong Kong. Mao was also unable to win back Taiwan, where the CCP's rival, the Kuomintang, had retreated after losing the civil war of 1945-49.

When Deng Xiaoping returned to power in 1977 after the Cultural Re- volution, he "regarded regaining Taiwan and Hong Kong as among his most sacred responsibilities", wrote Professor Ezra Vogel of Harvard University in his book, Deng Xiaoping And The Transformation Of China. In the end, Deng managed to regain sovereignty over Hong Kong, but not Taiwan.

From the get-go, Deng saw that a Hong Kong that remained prosperous and capitalist would benefit China in its modernisation drive, helping it in the areas of finance, technology and management.

Already, Hong Kong had been China's most important window to the world from 1949. "Beijing used Hong Kong as a place to earn foreign currency, import technology and gain information about the world," wrote Prof Vogel.

Apart from Deng's own desire to regain the British colony in the late 1970s in Hong Kong, the approach of 1997, when Britain's lease of the New Territories would run out, was causing anxiety. How would investors engage in long-term business activities if there was great uncertainty over the fate of 90 per cent of the territory?

It was arranged for then British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher to visit Beijing in September 1982 to discuss Hong Kong's fate with Deng. Mrs Thatcher went to Beijing to "exchange sovereignty over the island of Hong Kong in return for continued British administration of the entire Colony well into the future", she wrote in her book, The Downing Street Years. This, she wrote, was the solution that would suit the city's politicians and business leaders best.

Local political elites had reflected to the British government that they would like an arrangement in which Beijing would allow the British to continue governing Hong Kong as a caretaker administration. They were also of the view that it was not viable for the Hong Kong island and Kowloon peninsula to stand alone if the New Territories were to be returned to China, recounted Sir Chung Sze Yuen, 99, a former member of the Executive Council, in his memoirs Hong Kong's Journey To Reunification.

Deng made it clear that China wanted full sovereignty and this was not for discussion. However, to preserve Hong Kong's prosperity after 1997, its political system and most of its laws would remain in effect. He agreed that consultations should begin immediately but added that if the two sides could not reach agreement for the transition within two years, China would declare its policy unilaterally.

It took 10 months to get talks off the ground as the two sides could not agree on the basics: China wanted full sovereignty as the premise for talks and Britain wanted sovereignty to be discussed last. After some compromise, negotiations began in July 1983.

-

Two documents guarantee autonomy and rights for 50 years

-

Two documents adopted in the run-up to the handover of Hong Kong to China guarantee the city's autonomy as well as the rights and freedoms of its people for 50 years.

They are the Joint Declaration, signed between China and Britain in 1984, and the Basic Law, Hong Kong's mini- Constitution, adopted by the National People's Congress (NPC), or Parliament, in 1990.

The Joint Declaration stipulates, among other things, that:

• The Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (SAR) will be directly under the central government of China and that it will enjoy a high degree of autonomy, except in foreign and defence affairs;

• The SAR will be vested with executive, legislative and independent judicial power and that the laws currently in force will remain basically unchanged;

• Hong Kong's government will be composed of local residents and a Chief Executive appointed by the central government based on results of elections or consultations held locally;

• Hong Kong's current social and economic systems and the lifestyle of its people will remain unchanged. Rights and freedoms will be insured by law.

In an annex, it was stated that Hong Kong's previous capitalist system and lifestyle will remain unchanged for 50 years.

These elements were taken into the Basic Law. But some elements of the Basic Law have proved controversial:

• Article 23, which says Hong Kong shall enact laws on its own to prohibit any act of treason, secession, sedition or subversion against the central government. To Hong Kongers, enacting such a law would infringe on their rights and freedoms, and 500,000 people marched in protest in 2003 against a move to do so.

• Article 45, which says the ultimate aim is the selection of the Chief Executive by universal suffrage upon nomination by a nominating committee.[/(BULLET_LST)]

The NPC's decision in 2014 that a nominating committee would select two or three candidates for popular election and that the Chief Executive would have to be appointed by the central government was reject- ed by pan-democrats in Hong Kong and sparked a protest.

Goh Sui Noi

After several rounds of difficult talks, in which Hong Kong residents were not involved, a Joint Declaration was signed in December 1984. The binding declaration stipulated that the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, as it would be called, would enjoy a high degree of autonomy except in foreign and defence affairs. The government would be made up of local residents and the current social and economic systems of Hong Kong would remain unchanged as would the people's lifestyle. Rights and freedoms such as of speech, press and assembly would be insured by law.

Thus, Hong Kong would return to Chinese sovereignty in 1997 under the "one country, two systems" formula that would be kept in place for 50 years. This principle was first formulated for reunification with Taiwan, but it was rejected by the island's leaders then and now.

After the Joint Declaration, the task of drafting the Basic Law, Hong Kong's mini-Constitution, began. It involved 36 people from the mainland and 23 from the city.

The pro-democracy members of the drafting committee tried but failed to ensure that the Chief Executive and legislative councillors would be elected democratically.

As a measure of how far apart Beijing and Hong Kong were, those in Hong Kong who wanted full democracy felt the Basic Law betrayed the city's people, while the Chinese thought the city was granted far greater autonomy than any Western government would have done for any local area under its rule.

In the 20 years after the handover or huigui - return in Chinese - instead of a narrowing of that divide, Beijing and Hong Kongers have grown further apart. To Hong Kongers, some of their worst fears - of erosion of their autonomy and rights and freedoms - are coming true. This began in 2003 with the attempt to enact an anti-subversion law which while provided for in the Basic Law was still seen by Hong Kongers as an infringement of their rights and freedoms. The city's government retreated from this as well as a 2012 proposal to introduce patriotic education in schools after street protests by Hong Kongers.

Beijing, on the other hand, is disappointed that Hong Kongers have not come to identify more with the motherland and that some residents are calling for self-determination and even independence instead. It sees this as a rebuff of China's sovereignty over the city.

This has led to the renewed call last month by Beijing to enact the anti-subversion law and to emphasise that the central government has comprehensive jurisdiction over the city.

The one country, two systems formulation appears to be shaky as Beijing and Hong Kongers look to another deadline - 2047, when this formula is set to come to an end.

Join ST's Telegram channel and get the latest breaking news delivered to you.

A version of this article appeared in the print edition of The Sunday Times on June 11, 2017, with the headline Hong Kong handover: 'One country, two systems' shaky two decades later. Subscribe