WORLD FOCUS

Identity crisis Hong Kong

Twenty years after its return to China, Hong Kong ponders its future as political and socioeconomic rifts deepen

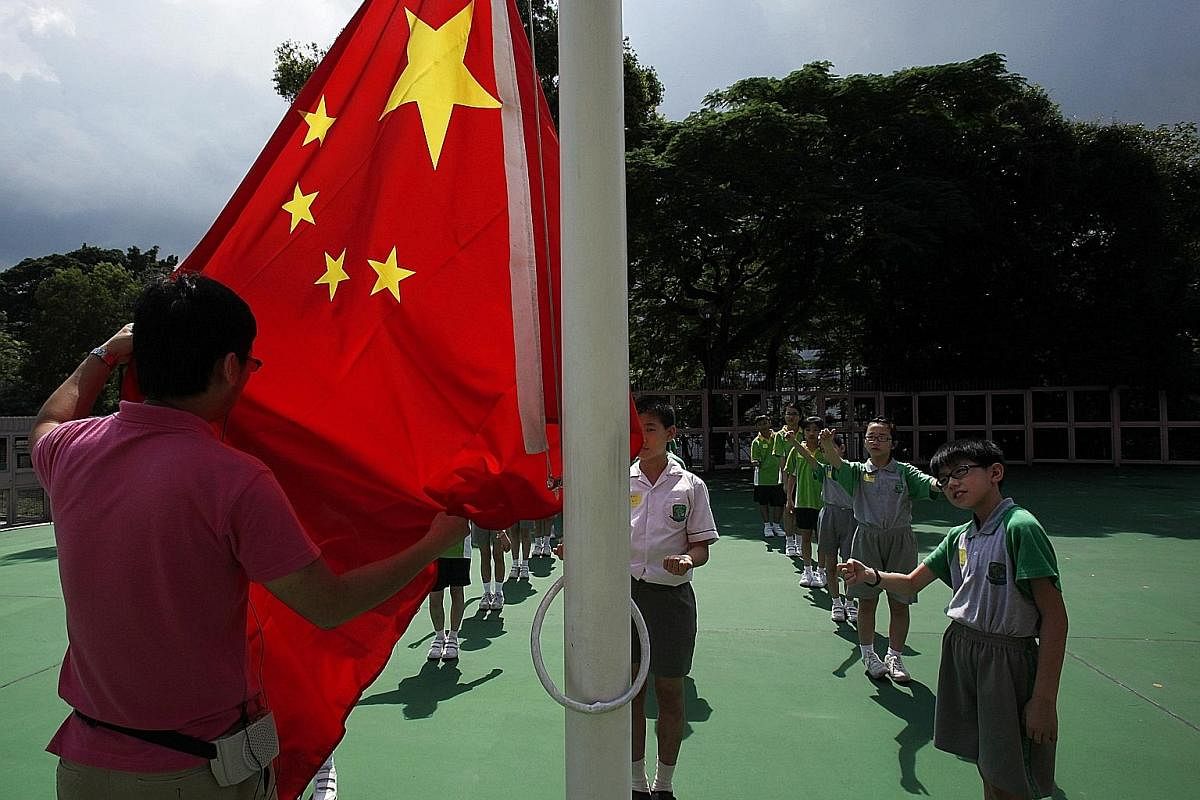

Hong Kong's incoming Chief Executive Carrie Lam wants to introduce national education, starting from kindergarten, so that the younger generation can identify more closely with China.

The government said in 2007 that it will work with various sectors to promote national education but the attempt eventually failed following strong opposition from Hong Kongers.

Parents saw national education as Beijing's way of brainwashing their children and also an encroachment on their rights and freedoms guaranteed under the "one country, two systems" framework, which gives Hong Kong a high degree of autonomy for 50 years.

A recent Hong Kong University survey of 120 Hong Kongers aged between 18 and 29 found that only 3.1 per cent identified themselves as "Chinese" or "broadly Chinese".

In stark contrast, in a 1997 survey, 31 per cent identified themselves as "Chinese in a broad sense" and 16 per cent as "Chinese".

Young people today see themselves as Hong Kongers first, then as Hong Kong Chinese and as Chinese last, the city's former chief secretary Anson Chan, 77, told The Straits Times in an interview.

Twenty years after the historic handover, the younger generation, especially those educated after 1997, are having an identity crisis, analysts say.

Born and raised in Hong Kong, they are used to the freedoms granted to the city. Hence, they are uneasy whenever Beijing intervenes in Hong Kong affairs.

Last year, Beijing's interpretation of the city's mini-Constitution led to the disqualification of two young democratically elected lawmakers.

In a recent interview with Xinhua news agency, Mr Charles Powell, who was private secretary to the late British prime minister Margaret Thatcher, said: "The younger generation in Hong Kong don't seem to remember or perhaps they never understood fully what was agreed in 1984 (Sino-British Joint Declaration).

"Hong Kong was never going to be independent, it couldn't be independent."

In Beijing's eyes, Hong Kongers' call for their own identity is a sign of separatism. But ask Ms Iris Tong, 46, and she uses strawberries to make her point. The fruit - or si dor bey lei in Cantonese - is increasingly being referred to as chou mei.

"Since we are in Hong Kong, we should be calling it si dor bey lei (instead of chou mei)... I'm afraid Hong Kong's new generation will not know what si dor bey lei is."

Mrs Chan suggests that Beijing should create a channel to communicate with young people and understand their concerns. Those who advocate self-determination have some very legitimate grounds, said Mrs Chan, who had a key role in overseeing the city's transition from a British colony to a Special Administrative Region of China.

Hong Kong youth want to have a say in their city's future, especially after 2047, when the "one country, two systems" model expires, because they feel "the British gave away their future without first consulting" them, said Mrs Chan.

"The 2047 deadline presents this opportunity and all they want is this opportunity to discuss and to tell Beijing what sort of Hong Kong they would like to live and work in. And this seems to me to be a very reasonable stance," she added.

The late Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping had promised that when Hong Kong was returned to China on July 1, 1997, its capitalist lifestyle would be unchanged for 50 years.

The city would continue to have "horse racing" and "dancing parties will go on", said Deng, who died five months before the handover.

Realising Hong Kongers' fear of communist rule, Deng made the pledge to set their hearts at ease, said retired legislator Emily Lau.

But the people soon realised that even if the system does not change, people's perspectives and the environment do. Ms Tong accepts that change is inevitable. And instead of resisting it, "Hong Kongers should be thinking about how to reflect our wishes", she said.

However, to 20-year-old Joshua Wong, achieving universal suffrage and self-determination for Hong Kong is the way to go.

"Political system reform and a free election is the way to protect Hong Kong and to oppose the interference of the rule of law by the Chinese government," said Mr Wong, who was barely a year old in 1997.

Mr Wong played a lead role in the 79-day Occupy Protests in 2014, sparked by Beijing's proposal for a nominating committee it controls to first vet candidates for the city's chief executive election. The proposal was eventually voted down.

The protesters' demand for "one man, one vote" also ended in failure.

Mrs Lam, like the three chief executives before her, was selected by an election committee stacked with Beijing loyalists. Many Hong Kongers saw it as Beijing breaking its promise to allow Hong Kong's leader to be popularly elected this year.

Lack of political determination aside, discontent among young Hong Kongers also sprang from socio-economic problems, such as income disparity and employment.

Many feel they do not have a good job and do not have a future when they cannot even afford a home.

For the seventh straight year, the 2017 annual Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey ranked Hong Kong the most expensive housing market in the world.

"The main gripe of young people is they cannot afford a home," said Ms Wing Tsang, 32, a hairstylist, who worries about not having a place to live in when she grows old.

Nevertheless, she has never once thought of leaving the city.

"I was born and raised here," she said, adding optimistically: "Hong Kongers are a resilient lot and we have always been able to recover quickly from a crisis."

A people and their city

Divided by age, wealth and politics, the people of Hong Kong will mark the 20th anniversary of its transfer from Britain to China with contrasting emotions: anger and pessimism, pride and joy.

Passionate about the future

STUDENT AND PRO-DEMOCRACY ACTIVIST CHAU HO OI, 20

Student and pro-democracy activist Chau Ho Oi, 20, holds a board upon which she wrote Chinese characters to sum up her Hong Kong. It reads "to hold onto".

Born in 1997 to a music teacher father and office worker mother, the student's earliest aspiration was to be a police officer.

Student rallies in 2012 against lessons promoting Chinese patriotism first made her realise young people could change things, says Ms Chau. She then went on to join a student activist group and became the youngest protester to be arrested during the youth-led Umbrella Movement rallies in 2014.

While some of her friends are politically apathetic and others frustrated by the lack of progress, Ms Chau says she wants to fight on as an activist. "I think I have the ability to change this society - we're not at the point of hopelessness yet. We have to create our own hope."

To the central government, young activists like her embody the rising tide of separatism in Hong Kong. Activists say they are pushing back against Beijing's growing interference in the city's affairs so as to preserve Hong Kong's unique identity and culture.

A survey released earlier this month showed only 3.1 per cent of Hong Kong's youth identify as "Chinese" or "broadly Chinese", a historic low. The Hong Kong University survey polled 120 young people between the ages of 18 and 29.

Chinese officials have stressed the need to strengthen national education to instil a stronger sense of Chinese identity among the young in Hong Kong.

AGENCE FRANCE-PRESSE, REUTERS

Worried for his children

FINANCIER CEDRIC KO, 40

Dynamic. That's how financier Cedric Ko sums up his Hong Kong.

Mr Ko spends his days working in a skyscraper overlooking Hong Kong's famous Victoria Harbour.

"Life in Hong Kong, compared to other cities, is much more vibrant. This is a great advantage for our competitiveness and commercial aspects of society," says the 40-year-old father of two.

But his enthusiasm is tempered by a feeling of unease about the future. He is concerned his kids may grow up blinkered in a conservative results-driven education system, which he believes does not encourage them to think for themselves.

And while Mr Ko and his family can afford a three-bedroom apartment, he worries the lack of space and comfort that others endure fosters public discontent.

Sceptical that Hong Kong can solve its political and social issues, he is one of a growing number of residents who hope eventually to emigrate. "I think the problems in Hong Kong will remain - if not get worse," he says.

AGENCE FRANCE-PRESSE

Things will get better

CHINESE MEDICINE SHOP OWNER TAN KIN HUA, 72

Chinese medicine shop owner Tan Kin Hua, 72, wrote the Chinese characters fan rong - prosperity - to sum up his hopes for Hong Kong over the next 20 years.

Many residents of his generation came from the poverty-stricken mainland and, like Mr Tan, sought an exit during the upheaval of the Cultural Revolution, which saw mass political purges. He shies away from talking about that time, saying: "It wasn't as free then."

Mr Tan arrived in Hong Kong by train in 1972 and started as a factory worker, earning just HK$8 a day.

After learning Cantonese, he moved into Chinese medicine which he had studied back home. By 1997, he was starting his own business, which he still runs today.

"My daughter is learning the trade... I hope to bring my experience to the younger generation," says the grandfather of two.

He criticises the 2014 democracy protests which brought parts of the city to a standstill for being "annoying", and he is also against the independence movement, arguing that Hong Kong is part of China and people should work together to improve its residents' livelihoods.

He has faith that life will improve in the years ahead.

"The Chinese government really supports the city. It will be better in the future."

AGENCE FRANCE-PRESSE

No regrets

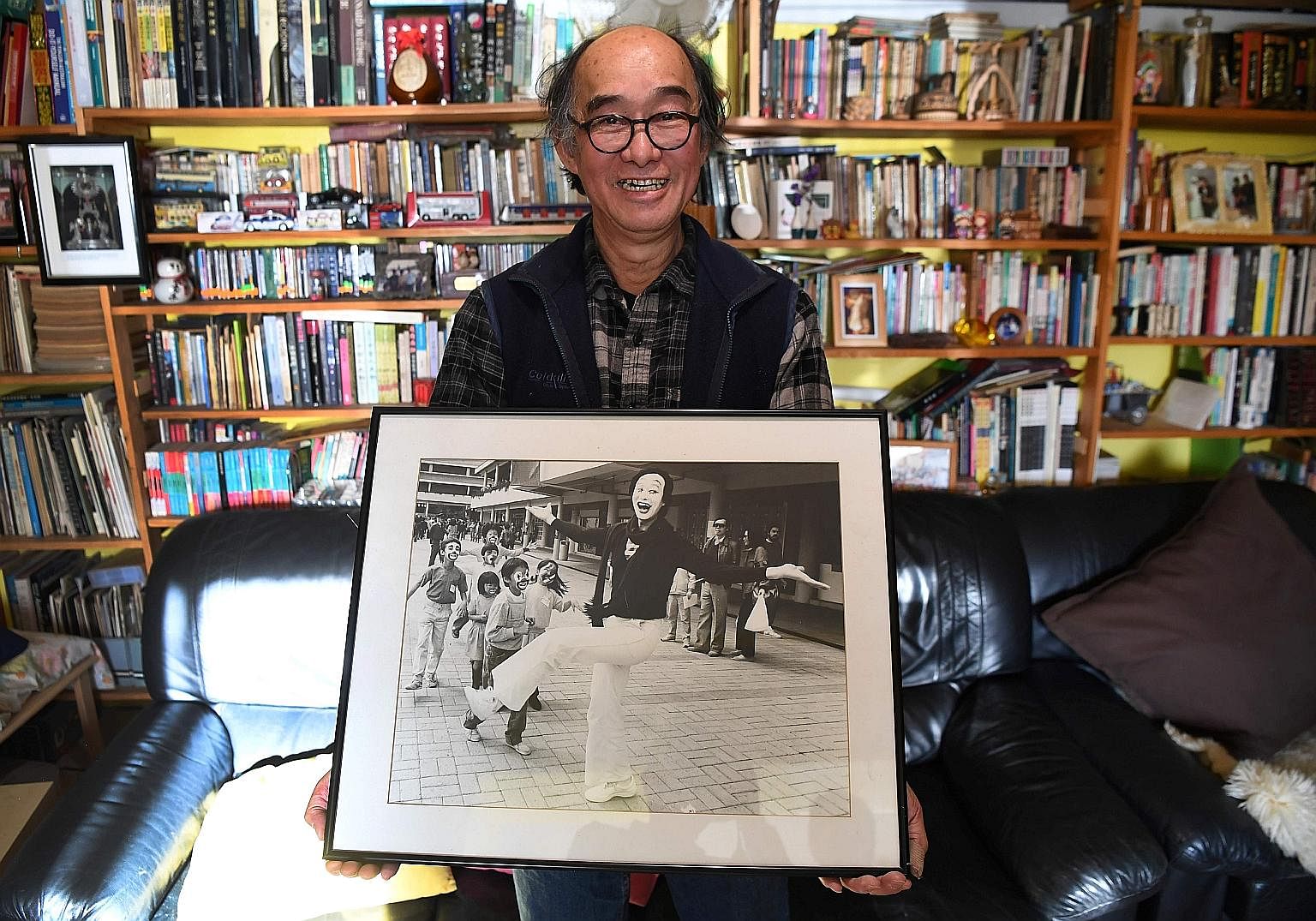

ARTIST PHILIP FOK, 69

Mr Philip Fok moved to Australia in 1992 with his wife and two children because he felt unsure of what would happen after July 1, 1997.

He says China's history under the Communist Party - including the Cultural Revolution which saw purges of political opponents in the 1960s and 1970s, as well as the Tiananmen Square crackdown in 1989 - played on people's minds.

Working as a mime artist at the time, he felt vulnerable because of his need for freedom of expression.

"To be free, to the artist, is very important," he explains.

He went to Sydney where he already had relatives, but says life was hard - he struggled to get a visa, knew little English and lived on benefits for two years.

However, he managed to set up a painting studio, which he ran until last year, and hosts a weekly Cantonese radio show in Sydney's North-west, where he lives.

Mr Fok says his fears for Hong Kong have not materialised, and he argues the city is more free now than in colonial times. But he has no regrets about leaving.

"In Australia, nobody cares about your dress, nobody cares about your money," he says, adding that artists there are held in higher regard.

There are no official emigration figures, but government estimates show hundreds of thousands left Hong Kong between 1990 and 1997, with the annual figure hitting 61,700 in 1990 and peaking at 66,200 in 1992.

Australia, Canada and the US were the top destinations and are home to thriving Cantonese communities.

AGENCE FRANCE-PRESSE

Join ST's Telegram channel and get the latest breaking news delivered to you.

A version of this article appeared in the print edition of The Straits Times on June 27, 2017, with the headline Identity crisis Hong Kong. Subscribe