With a bag of fertiliser slung across his back and a shovel in hand, 41-year-old Pubu Langjie tended to the endless rows of liquorice and fruit tree saplings that have only recently been planted across the arid soil of Dranang county.

It's tiring work under the scorching Tibetan sun, but Mr Pubu, formerly an itinerant worker, is glad for the job, which was offered to him after he relocated from his remote mountaintop home 30km away.

"It pays 4,000 yuan (S$796) a month, about the same as my previous odd jobs, but the work is easier and much more stable," he said, adding: "I no longer worry when I'll see my next pay cheque."

Improving the fortunes of those like Mr Pubu is why China has pushed for drastic solutions like relocation in its war against poverty, which Beijing has intensified after President Xi Jinping came to power in 2012.

This year alone, China will relocate 2.8 million poor people, part of an urbanisation push to move 100 million villagers to cities by 2020.

Nearly four decades after Beijing began tackling the deep-set problem of destitution, Mr Xi vowed in 2015 to completely eliminate extreme poverty in China by 2020.

Even before that goal is reached, China has played an outsized role in the global reduction of poverty.

-

2.8 million

Number of poor people who, this year alone, China will relocate, as part of an urbanisation push to move 100 million villagers to cities by 2020.

30 million

Number of poor people still living in the world's second largest economy, as of this year.

$21 billion

How much China's central government has budgeted in its special fund for poverty alleviation this year, a dramatic seven-fold increase in just one decade.

In 1978, over 90 per cent of China's population of one billion - with the bulk in rural areas - were considered indigent, living under the extreme poverty line set by the World Bank that today is US$1.90 (S$2.60) a day.

Then paramount leader Deng Xiaoping unleashed reforms that same year that ranged from ending rural farming communes to designating special economic zones in coastal cities that saw a flood of foreign investment. The measures ushered in an era of roaring growth that saw per capita income soar 16-fold in the next three decades, noted World Bank country director for China Bert Horfman. The result was over 700 million people escaping poverty, nearly half of global poverty reduction then.

But the concentration of economic liberalisation and investment in coastal cities in recent decades - even as agricultural land reform slowed - meant that the rural poor have stayed a stubbornly difficult problem for Beijing.

As of this year, there are still 30 million poor living in the world's second largest economy.

Mr Xi, who has tied his job performance and that of local officials to ensuring no Chinese remains under the poverty line after the 2020 deadline, has spared no expense.

The central government budgeted over 106 billion yuan (S$21 billion) in its special fund for poverty alleviation this year, a dramatic seven-fold rise in just one decade.

But why is defeating poverty of such importance to Mr Xi and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)?

Experts say there is a political and existential imperative for the CCP to erase poverty, having in an earlier era promised a society centred on egalitarianism and prosperity for its peasants.

To be sure, the vast mobilisation of money and people in recent years has paid off: since 2012, about 13 million people a year have risen above the poverty line, double that of the decade before, said Mr Liu Yongfu, director of the State Council Leading Group Office of Poverty Alleviation and Development.

One reason for the successes is that Beijing has better localised its policies and learnt from past mistakes, such as the wholesale relocation of villages without putting in place sufficient support networks, community services and jobs.

Schemes to help farmers get loans and the expertise to tap local conditions and specialities have been expanded to maximise returns from agriculture, such as rare black bee honey in frigid Heilongjiang, kiwi fruit in Sichuan, or mulberry to make artisanal paper in Guizhou.

With China's greater focus on high-quality growth and environment protection, more firms are tapping local unskilled labour in ecologically vulnerable places that often also have poverty problems, said Mr Liu. These include combatting desertification by planting crops like desert squash and sea buckthorn in Inner Mongolia.

Where feasible, Beijing has encouraged rural communities to stay put by spending big to upgrade homes and basic infrastructure in the villages, ensuring even those living in remote places have access to water, electricity, roads, mobile networks and services such as medical care and education.

Such is the case in Naduo village in the Wenshan Zhuang and Miao autonomous region of Yunnan, one of the poorest provinces. In 2016, 70 mud shacks with erratic power and water there and in nearby villages were transformed - free of charge - into charcoal-bricked homes. Dirt roads were cemented over, and solar street lamps were installed.

However, many gaps remain in Chinese society, such as the urban-rural divide. Those living in cities make, on average, three times the income of those in rural areas.

And China's Gini coefficient - a measure of income inequality - has climbed rapidly in the last two decades to between 47.3 and 50 points, among the world's highest.

Ms Hannah Ryder, who heads an international development consultancy in Beijing, noted that with China's push to have one billion people living in urban areas by 2030, the gap with those "left behind" in the countryside - who are mostly the elderly and children - is likely to grow starker.

Further hukou (residential permit) reform to prevent discrimination against farmers migrating to the cities, coupled with financial incentives to return to rural areas and better redistribution of wealth and resources to the rural areas, will be needed, she told CGTN, a Chinese news channel.

Experts stressed that eliminating extreme poverty, while laudable, is just a first step. Mr Horfman estimated that some 54 million Chinese will still be classified as "population vulnerable to poverty", living on US$3.10 a day or less.

"As China drives forward forcefully in its campaign to eliminate extreme rural poverty by 2020, the conditions in the remaining poor areas are particularly difficult, and the obstacles to success particularly large," said United Nations resident coordinator for China Nicholas Rosellini. "Simply pouring more and more resources into this effort is not always the best approach to such challenges."

But Mr Lu Mai, who is secretary-general of the China Development Research Foundation, a public organisation, said China is looking beyond its 2020 goal and drawing up plans to ensure that those who have escaped poverty will not fall back in.

Some local governments, for instance, are already looking at a higher poverty line of 4,500 yuan in annual per capita income compared to the current 3,000 yuan.

"China is carrying out poverty alleviation work in an evidence-based manner, learning from methods abroad while formulating policies based on closely monitored results, so I'm confident we will succeed in erasing poverty for the long term," he said.

Public foundation gives poor kids a leg up

In an age of talking books and flashy toys, a sock puppet and a plastic bottle feel like poor substitutes for holding a toddler's attention.

But two-year-old Xu Qirui was spellbound by his new toy car - fashioned out of the bottle and with the puppet "driver" at the wheel - a gift from a home educator who visits him every week. "Can you pull the car in the opposite direction from auntie? Clever boy!" encouraged Ms Gu Qiaomei, 33, the educator.

As Qirui raced around his cave home in mountainous Qiaochuan township of Huachi county in Gansu - one of China's poorest provinces - Ms Gu taught his grandmother and caregiver Ren Hongnu, 46, how to turn the toy into sessions of directed play that would teach the toddler six concepts: go, stop, accelerate, slow down, far and near.

"You can ask him to pull faster, and slow down, and over time he will understand speed," said Ms Gu.

Qirui is one of 60 million "left-behind" children in China - young people who grow up in the care of illiterate grandparents in rural areas as their parents have left for the cities for better jobs there.

As China realises the importance of early childhood education in breaking the poverty cycle across generations, there is increasing attention given to bringing such education to children like Qirui.

Between the ages of zero and three is when the brain undergoes critical neurodevelopment, said Mr Lu Mai, secretary general of the China Development Research Foundation (CDRF), a public foundation. Studies have shown this is a critical time for learning.

While practices such as reading bedtime stories have become commonplace in the city, many older village folk lack such knowledge so a rural child reaches kindergarten far behind his city peers.

"(Rural) parenting methods directly impact the development potential of a child, and solidify the social gaps, passing poverty on to the next generation," he said.

This is where Ms Gu, one of more than 300 home educators working with CDRF, comes in. For an hour each week, she visits nine children in the county, many living in remote mountain villages. She plays games, draws and sings with them.

She also teaches their caregivers better ways to interact with the children, aged from six months to three years.

The pilot programme in Huachi, which started in 2015, saw early fruits just one year in: A survey showed that developmental risk was cut by half while the family environment of most of the toddlers had improved.

The programme has since been expanded to the rest of Gansu as well as Guizhou, Xinjiang and Qinghai, some of China's poorest areas.

Dance a passport out of poverty

With arms interlinked and laughing as they kicked their heels to the rhythm of a three-string lute, the dozen young girls of the Yi minority group showcased their traditional ethnic dance, an art form that had nearly disappeared in their small mountain community.

But the brave smiles of those like Zhang Yuqian, 12, masked apprehension, as the dance item was part of a ceremony that marked a new chapter for the next generation of remote Naduo village, which in the Yi dialect means "paddy fields hidden behind the mountains".

Yuqian, together with 54 other children, would travel nearly 350km the next day - the farthest she would ever be from home - to begin her schooling in the provincial capital Kunming. She would not see her parents for the next six months while studying at Kunming Art School.

"I'm worried that I may not fit in in the city, but I'm also happy because it shows that Teacher Zhang and Teacher Guan's instructions have not been wasted," she said.

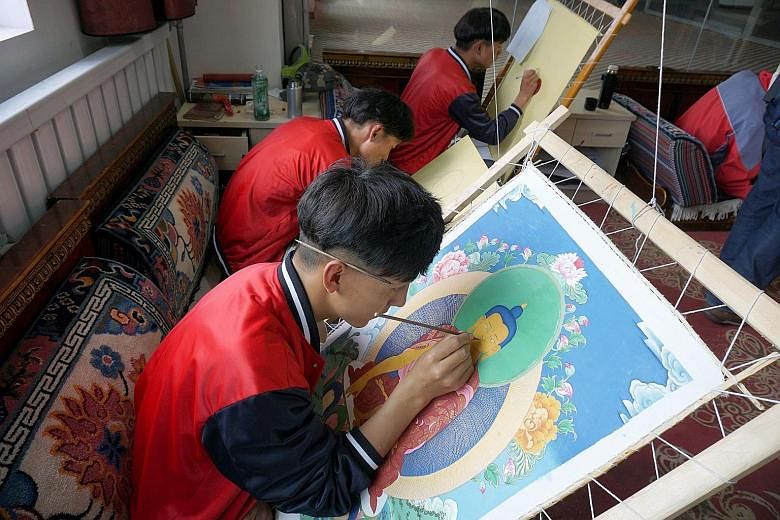

The two teachers are choreographer Zhang Ping and ballet teacher Guan Yu with the prestigious Beijing Dance Academy, who in 2016 began the Rainbow Project. This is a ground-up initiative that seeks to lift minority children in Yunnan's Wenshan Zhuang and Miao autonomous prefecture, of which Yuqian's village is a part, out of poverty through the arts.

There are no records of anyone from the village, one of the poorest in the region, completing a degree or diploma. The traditional career path, after completing secondary school, is that of a migrant worker working in a low-paying service or manufacturing job in one of the nearby cities.

The Rainbow Project hopes to change this.

Last year, Mr Guan and Ms Zhang raised funds to send four children from Naduo to Kunming Art School after the quartet passed its rigorous entrance examinations, following weekly dance lessons with volunteer teachers from local schools.

Despite the odds, the students did well enough that the school and its affiliate, the Yunnan Art School, offered another 51 scholarships this year, Ms Zhang said.

But there were some problems too. There were a few instances of truancy, which was eventually traced to difficulties adjusting and homesickness, Mr Guan said.

"The city moves at such a fast pace, unlike back home, that sometimes I miss the simple life I had of picking mushrooms and grazing the cows," said 14-year-old Wang Shiyi, one of the four children.

Lim Yan Liang