The hundreds of thousands of visitors who travel each year to Australia's Ayers Rock, or Uluru, face a difficult moral choice: to climb or not to climb.

The 700-million-year-old monolith in central Australia is one of the country's best known tourist landmarks, but the steep climb to the top has been at the centre of a bitter and long-running dispute.

The Aboriginal people who are the traditional owners of the land regard Uluru as a significant sacred site and are largely against visitors climbing it.

The area around the famous 860m-high rock contains Aboriginal paintings, engravings, walking tracks and cave shelters, which are more than 5,000 years old and are believed to be evidence of one of the oldest continuous cultures in the world.

The federal government's position, laid out in a management plan in 2010, is to close the climb eventually. But opponents say this will affect tourist numbers and detract from the experience of visiting the rock.

The passionate dispute was reignited last month by the Northern Territory's Chief Minister, Mr Adam Giles, who called for the Aboriginal custodians to reconsider their opposition to the climb.

Addressing the state Parliament on April 19, he said the government should consider creating a "climb with stringent safety conditions and rules enforcing spiritual respect that will be endorsed, supported and even managed by the local Aboriginal community".

"It would capture the world's attention with a culturally sensitive tourism product delivering an unforgettable experience in the spiritual heart of Australia," he said.

"There would be significant economic benefits for the local indigenous population and there would be economic benefits for the Northern Territory."

More than 35 people have died during the arduous, 1.6km climb up Uluru since the 1950s, mostly from heart failure. Last year, a 27-year- old Taiwanese visitor fell 20m into a crevice and spent the night on the rock before being airlifted to hospital with head injuries.

The falls have added to the opposition to climbing by the Aborigines, who believe they are responsible for the fates of visitors and are required to grieve for anyone who is injured or dies.

Mr Giles insisted that more visitors would climb the rock if it was backed by the local Aboriginal people. Trumpeting the potential benefits to tourists, he cited the opening of the Sydney Harbour Bridge to climbers in 1998; more than three million people from over 100 countries have done the climb.

"There are plenty of examples worldwide of culturally sensitive sites and tourism experiences combining successfully, for example, the temple Angkor Wat in Cambodia, the Taj Mahal in India and Machu Picchu in Peru all coming close to mind," he said.

But the comments triggered a fierce backlash and prompted calls for the federal government to push ahead with a ban.

The Central Land Council, which represents the area's Aborigines, described the comments by Mr Giles as "completely wrong" and offensive to Aboriginal traditions.

"The issue of climbing is not an issue of safety, but an issue of ceremony, and they (the local Anangu people) want it protected," council chairman Francis Kelly told National Indigenous Television.

A federal Labor MP whose electorate is in the Northern Territory, Mr Warren Snowdon, described Mr Giles as "ignorant" and urged him to "show some respect".

"The traditional owners have made it quite clear they'd prefer it if people didn't climb Uluru," he said in a statement.

The ruling federal coalition has supported keeping the climb open but says it will continue with a plan introduced by the previous Labor government in 2010 which states that the trail will be closed when the proportion of visitors who climb falls below 20 per cent.

Reportedly, this figure could soon be reached as only about 20 per cent currently climb.

About 300,000 tourists visit the site each year.

A sign at Uluru's visitor centre urges people not to climb. "That's a really important sacred thing that you are climbing," it says. "You shouldn't climb."

Research from Parks Australia has shown that 98 per cent of visitors would still go to Uluru if climbing were to be banned.

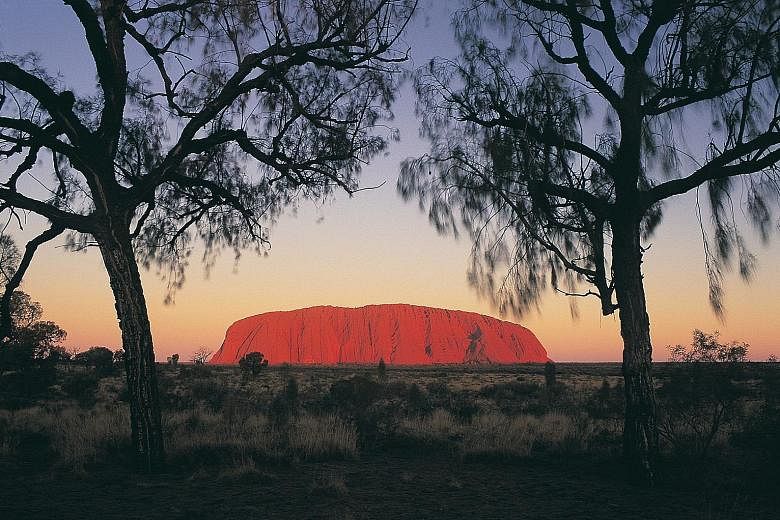

Indeed, some of the most famous images of Uluru are not taken from the top but from afar, showing the region's famously spectacular sunset with the rock in the background.

In any case, many visitors are unable to climb whether they want to or not because strong winds at the site frequently prompt the local authorities to close the trail.