Australia has long been renowned for its deadly wildlife, including sharks, crocodiles, snakes and even jellyfish. But experts believe its fearsome reputation may no longer be warranted.

In recent years, the discovery of anti-venoms has put a damper on the deadliness of some creatures, and new research has shown that the threat from Australian snakes may have been overstated.

In addition, efforts to warn people of the risk from creatures such as jellyfish and crocodiles have helped to reduce the number of deaths.

A visitor programmes coordinator at The Australian Museum, Mr David Bock, said deadly creatures kill only six to 10 people each year in Australia - far less than the number that die in car crashes or just crossing the road.

"It is a very small handful who die each year from deadly animals," Mr Bock told The Straits Times. "The animals themselves can be very dangerous but humans have learnt to be very wary of them. In most cases, the deaths involve an accident or things such as alcohol, which can lead to people taking risks."

A long-held belief is that 20 of the world's 25 most deadly snakes are found in Australia - a notion that emerged in the 1970s following research on mice.

But scientists have begun to question the claim.

An Australian toxicologist, Professor Geoff Isbister, from the University of Newcastle, said the 1970s research was "not entirely untrue but not quite right". The effect of toxic snake bites on mice, he said, may differ from the impact on humans.

"A more accurate statement might be that Australian snakes are the best mouse killers in the world - they're able to kill the most mice with the smallest amount of venom," Mr Isbister wrote on The Conversation website two weeks ago.

"Severe snake-envenoming is actually quite rare in Australia, with only about 100 cases each year," he added.

It is true that Australia is home to the world's deadliest snake - the inland taipan, which is found in the country's central region.

Its venom is the most toxic in the world - a single drop is said to be able to kill 100 adult men. But no fatal bites have ever been recorded.

Experts say this is because the snake is shy and lives in remote areas where it has little contact with humans.

Prof Isbister said tiger snakes and death adders have historically caused the most deaths in Australia - by paralysis. But the development of anti-venom - in the 1930s and 1950s - and medical improvements meant that paralysis from snakebite has now become uncommon.

About one to five people still die from snake bites in Australia each year, mainly from brown snakes, which can cause cardiac arrest.

"Unfortunately, anti-venom is unlikely to help people bitten by brown snakes because cardiac arrest happens within 30 minutes of the bite," Prof Isbister said.

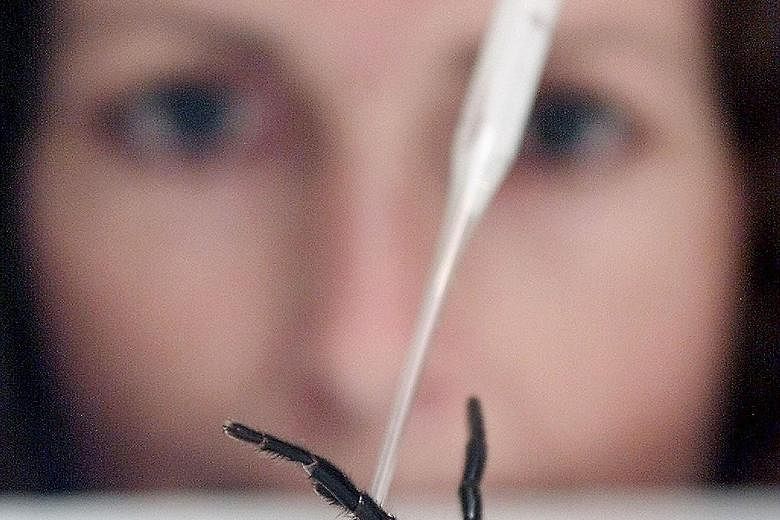

Australia also has two deadly spider species - the funnel-web and redback. But no deaths caused by them have been recorded since the introduction of anti-venoms in 1981.

The number of crocodile attacks have also declined to less than one death a year in Australia, despite rising figures in some other countries.

Experts say the drop is due to culls, warning signs at waterways, and management techniques such as controlling some areas as "crocodile-free zones". These measures have also helped cause a drop in the fatality rates per attack to about 29 per cent, compared with rates as high as 72 per cent in Timor Leste and 49 per cent in Sumatra, according to an analysis in 2013.

Despite Australia's overall success in reducing deaths from dangerous wildlife, there is one exception: sharks. There have been 14 deaths in the past four years alone, compared with an average of about one fatal shark attack a year in the whole of the last century.

Experts say there is no clear reason for the recent increase. Possible explanations include changing breeding and migration patterns due to rising water temperatures, and an overall rise in the number of people swimming and surfing in Australian waters.