This story first appeared in The Sunday Times, Dec 21, 2014.

My rented car comes to a halt along a dusty, derelict village road lined by small stores hawking biscuits and bottled water. Skinny black goats graze by the wayside. A thin, greying man sits alone on a boulder, idly eyeing the afternoon traffic.

"This is the closest we can get to Nallavadu beach, Madam," my driver Jaiprakash Kalirajan, 40, says, looking up from the GPS app on his Samsung phone. "Do you have an address for where you have to go?"

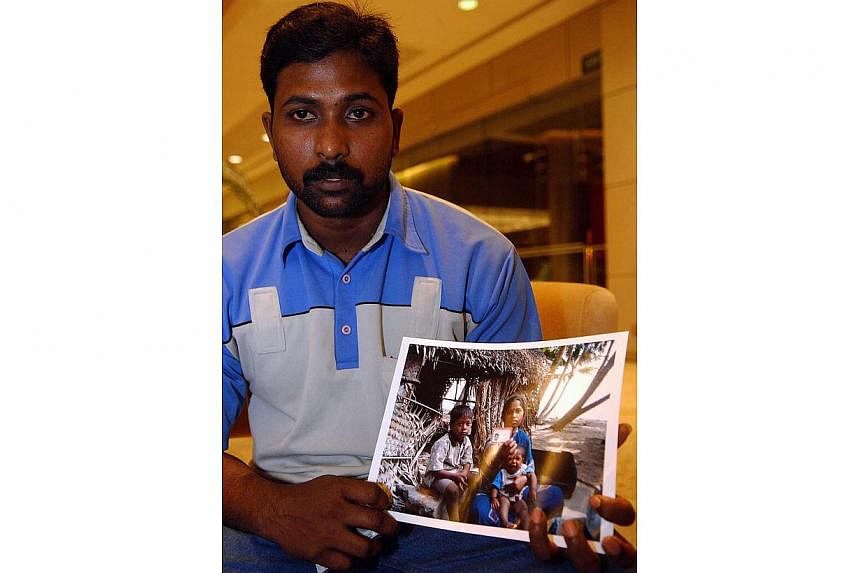

All I have are a million memories. And a 10-year-old photograph of a grim-faced young woman sitting with two small boys before their wrecked beachside hut.

Days after the Indian Ocean tsunami pulverised thousands of coastal hamlets in more than 14 countries a decade ago, I visited Tamil Nadu's Coromandel Coast, which bore the brunt of the disaster in India. More than 18,000 people died there, mostly in the coastal towns and villages known till then for beautiful beaches and fresh seafood.

I returned there last week, hoping to catch up with the survivors I met and wrote about in this newspaper immediately after the tragedy and, once more, a year later, in December 2005.

But I have no address.

I hold out the photograph to the man on the boulder, asking in broken Tamil: "Do you know her?"

Mr K. Selvan peers intently at the photo and seconds later looks up, yelling excitedly in English: "Tsunami! Tsunami!" He gestures for us to follow him.

In less than 10 minutes, we are staring at an impressive double- storey house with a blue-and- gold-flecked iron gate. It's unlocked but no one seems to be home. Unperturbed, Mr Selvan takes off again, muttering that she must be visiting her mother nearby.

We follow him and a couple of barefoot children tag along, asking for chocolates. Suddenly, we turn a corner and there she is, squatting by the roadside, chatting cheerfully with a group of friends.

I cannot believe my luck. This is serendipity.

'I NEVER WANT TO LIVE ON THE BEACH'

As I smile at Ms Vijaylalitha Kandan, 35, and wave the photograph at her, recognition dawns immediately. "Singapore pattirikayalar," she exclaims, using the Tamil word for journalist.

When we first met a decade ago, the young mother was on her haunches, sifting furiously through wet debris in her wrecked thatched hut, searching for the phone number of her husband, B. Kandan, 36, an electrician in Singapore.

Although he knew that his family was safe, he had no idea that their home had been destroyed, their cash and worldly possessions all consumed by the turbulent tide.

The Straits Times ran a pair of stories and photographs about the couple's plight, describing the homeless mother with two young sons in India, and her husband's anguish at being unable to go to his family - he was too poor to leave his job in Singapore.

Their story struck a chord with readers of The Straits Times immediately. Thanks to their generosity, Mr Kandan was able to go home by mid-January 2005, armed with an air ticket, a bagful of clothes and around $7,500 in cash. Top on his agenda: reuniting with his family and starting to build a house that would withstand the waves, should a tsunami strike again.

Ten years on, Ms Vijaylalitha, now 35, proudly leads me to her spacious new home, which the family moved into earlier this year.

The mud floor of a decade ago has been replaced by polished granite. Instead of the crude thatch door, she has an ornate wooden one carved with an image of the elephant-headed Hindu god Ganesha, the harbinger of good luck and prosperity.

The house is a good 15-minute walk from the sea. "I never want to live on the beach - it's too dangerous," she explains.

These days her biggest preoccupation is to ensure that her two sons, Abhi, 14, and Ashwin, nearly 11, get a good education. Both go to a private English medium school, funded by their father's hard work. "This house and their education - that's all we spend our money on," she says.

Abhi, who will take the Indian equivalent of the O levels next year, dreams of becoming an engineer. His father is still in Singapore.

'PEOPLE PITY US LESS NOW'

As the afternoon dissolves into evening, I continue my journey towards Nagapattinam, the Tamil Nadu district which was ground zero in India's tsunami tragedy. More than 6,000 people died there.

The first time I travelled these roads days after the disaster in 2004, they were a mangled mess of bodies, boats and broken bridges. And though many of the dead had been cremated, the ineffable stench of death still hung heavy in the air.

The overflowing refugee camps have long closed their doors; bridges, schools and roads have been rebuilt.

The next morning, I visit Mr Karibeeran Parameswaran, who was doing well as an engineer and a happily married father of three until he lost all his children and seven relatives to the killer waves. He still tears up recalling how he dug his children's graves with his bare hands.

He was 40 and his wife, Ms P. Choodamani, was 37 when their lives were smashed. They made a pact to end their lives, but after spending a couple of days locked in prayer, the devout Christians believed they had been saved for a purpose. They decided to stop weeping at their fate and opened their large home to tsunami orphans.

When I first met them nearly a decade ago, they had adopted 16 orphans. Today, their brood has grown to 37, including children who have lost parents more recently and have no one to care for them.

They have also been blessed with two chubby-cheeked sons of their own, Shemayiah, nine, and Michaiah, seven. "People pity us less now," says Ms Choodamani. "And for that we are thankful."

Both husband and wife still hold full-time jobs in the same state-owned companies they worked in a decade ago. He is an engineer with Oil and Natural Gas Commission and she an officer with the Life Insurance Corporation. Their family income has risen threefold in a decade and much of it goes to fund Nambikkai - or Hands of Hope - the children's home.

Their fierce faith and courage in the face of calamity have won many admirers and accolades. And laughter has returned to their home.

But the pressures today are greater than in the idyllic days before the tsunami, says Mr Parameswaran, as he deftly braids the long hair of his wards getting ready for school. "Imagine having 39 kids of your own," he laughs. "That's the pressure I am talking about."

'WE CAN NEVER FORGET'

I move on to other villages dotting the azure coast. The tears have dried, people are earning more and many have rediscovered a new purpose in life.

Chatting with villagers, I discover the same resilience I had noticed on other visits to tsunami-hit communities in Indonesia and Sri Lanka.

Big tragedies don't always break the human spirit. They can, in fact, burnish it.

At Akaraipettai village, I show villagers another old photo and they lead me to the doorstep of Ms Kumari Sivakumar, 38, who lost both her children - daughters Nithya, seven, and Sandhya, four - to the killer waves.

When we first met a year after the tsunami, Ms Kumari was pregnant. Her son Kamalesh, now a cherubic nine-year-old who "loves to study", has given the housewife and her fisherman husband N. Sivakumar, 40, new reason to live.

The family lives in a small tin-roofed, box-shaped home built for tsunami survivors. "My son makes me happy," says Ms Kumari, though her face is bereft of a smile.

She seems tense as we speak. Then she lets on that she is bracing herself for this week's memorials to mark the 10th anniversary of the tsunami, and the inevitable memories that will come flooding back.

"We can never forget what happened, and the little girls we lost," she says sadly.

Life has looked up for them, but the pain lingers on.